The Flight From Hitler's Shadow

Contextualizing Third Reich revisionism (and Darryl Cooper's sources)

“Thus, from the very start, the debate has been locked into two opposing interpretations. Each side has become increasingly entrenched in its own position, and the possibilities of a more nuanced view, in which a synthesis of the most persuasive features of each could be achieved as the basis for moving research forward, has been rendered all but impossible. Such is the political sensitivity of the issues in question, such is the moral charge with which each attempt to stake out a position on these matters has become loaded, that even the slightest move to criticize the one or the other, to mediate between them, or to go beyond them, has met with violent polemics, accusations of trivialization, moral denunciation, and allegations of trying to undermine the […] political system.”

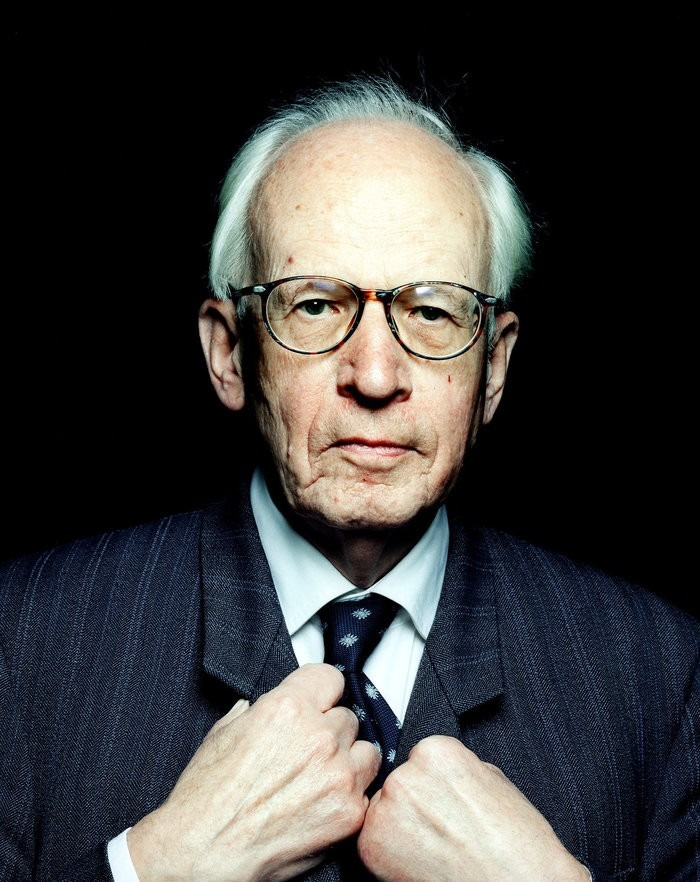

—Richard J. Evans, In Hitler’s Shadow

…

Something I have come to appreciate more as I wrap up my second year of graduate school—much to the annoyance of likely everyone in my life, not least of which my partner Molly—is the importance of getting the details right. Learning when, where, and how to deploy corrections is clearly a craft, if not an outright art, and it is not something that comes easily to historians and especially students trying to become historians. However, as I suggested in my recent post reflecting on the brief appearance my words made in the New York Times, I think it is important for those of us engaging with history professionally to constantly be chipping away at any lack of clarity that exists, whether deliberately or accidentally.

Whether he likes it or not (and it does not really matter, since he did bring it on himself) Darryl Cooper will forever be associated with David Irving, thanks to him both praising Irving on more than one occasion over on X, thanks to him admitting that the “Churchill being bought off by Zionists” canard he referenced in the Tucker Carlson interview came from Irving, and thanks to him, in a rare display of transparency, showcasing his stack of secondary sources that included some of Irving’s work. However, because people keep talking about him and his work (thanks to his Rogan appearance and the Murray v. Smith debate), it has become a bit of a meme to say that all Darryl is doing is giving us “warmed over” or “reheated” David Irving arguments.

The thing is, much as I can appreciate the reality of this, it oversimplifies the approach that Darryl is taking and is ultimately not all that accurate. The morally dubious revisionist approach to the history of World War II and the Holocaust does not begin or end with David Irving. It would be more accurate to point out that what Darryl is reheating is an argument that animated West German historiography during the 1980s known as the Historikerstreit. This argument—made largely between German historians of the left and right—was something into which Irving inserted himself and took to its now-well-known conclusion thanks to Irving’s own litigious histrionics and Jew-hating obsessions. This does nothing to make Darryl’s indulgence of Irving any less problematic, but it does provide an opportunity to both provide some context for the kinds of arguments Darryl has made and will likely be making as his series on World War II from the German perspective continues, provided he does not pivot toward other sources. More importantly, it is just a really interesting window into how German historians grappled with their country’s past that still existed in living memory, but had sufficiently faded for it to become somewhat less verboten to try out a little more revisionism here and there.

I had been very lightly aware of the debate at the center of the Historikerstreit thanks to passing references made in the historiographical sections of the books I read for my own historiographic analysis of Holocaust histories, but my attention had been more directed at the older split in the historiography—that is, between the functionalist and intentionalist school of thinking when it came to the Nazis and the Final Solution. That debate—that is, whether the genocide of the Jews was a function of the war or an objective of the Third Reich—had already been put largely to bed by the time the Historikerstreit kicked off in the 1980s, but it provided a necessary background in that it got down to the fundamental essence of studying the Third Reich: how do we distribute responsibility for the greatest crime of European history that occurred under our people’s—that is, the German people’s—watch?

The answers to that fundamental question took on new contours after the functionalist vs. intentionalist debate began to fade from relevance and the 1970s became the 1980s. Contextualization and historicization became the new five dollar words for historians in West Germany, with everything (except the existence of the Holocaust itself; again, that was Irving’s game, along with other neo-Nazis) being called into question, including the very idea that the Holocaust even was the greatest crime of European history. That was the limit of what I understood about the Historikerstreit, but thankfully, there was a readily-available source in the form of the celebrated Third Reich historian Richard J. Evans’ excellent 1989 monograph, In Hitler’s Shadow: West German Historians and the Attempt to Escape from the Nazi Past. This slim volume is a piece of pure historiography—the history of the study of history—but given its publication date, it arrived in the immediate aftermath of the Historikerstreit and could even be considered something close to a primary source.

Evans is by no means above reproach—many of his conclusions and interpretations of the East-West split of Germany are very much of their era and do not age well. However, as a fluent speaker of German and a Third Reich expert in his own right, there really was no better source than this one for me to get a much better grasp of the main areas of contention and revisionism that flared up in the 1980s. It also took very little time for me to realize that I had heard a lot of these arguments—or, to use my own five dollar word again, the contours of these arguments—more than once before, specifically from another historical podcaster. But we will return to those similarities later; what is important for us to look at now is just what these arguments actually were and how they came about.

The Historikerstreit began in the aftermath of a May 1985 event known as the Bitburg controversy, during which United States President Ronald Reagan attended a ceremony at a German military cemetery in Bitburg to honor the 40th anniversary of the end of World War II. Unfortunately, of the 2,000 German soldiers buried there, 49 were members of the Waffen-SS, the long-understood “true villains” of the Third Reich (the “myth of the clean Wehrmacht” had not fully been put to bed by 1985, and in fact, served as a debate pillar during the Historikerstreit). This resulted in a wave of controversy, particularly in the United States after Reagan defended the visit to the ire of a number of government officials, U.S. Army veterans, and members of various Jewish American communities. While it has been claimed that his notorious Communications Director Pat Buchanan wrote the response (who denied it in 1999), the Reagan administration stated the following in his defense:

These [SS troops] were the villains, as we know, that conducted the persecutions and all. But there are 2,000 graves there, and most of those, the average age is about 18. I think that there's nothing wrong with visiting that cemetery where those young men are victims of Nazism also, even though they were fighting in the German uniform, drafted into service to carry out the hateful wishes of the Nazis. They were victims, just as surely as the victims in the concentration camps.

This was when a very obvious politically-motivated split began to occur in the name of German history, and the Historikerstreit could begin in earnest.

One cannot escape a number of names when discussing the Historikerstreit controversy, especially the most controversial among them: the German philosopher-turned-historian Ernst Nolte. Nolte and his arguments had already held prominence in German intellectual life, and his arguments that defined his position in the Historikerstreit had already existed in print for a number of years. But just over a year after the Bitburg controversy erupted in both the United States and German media, Nolte officially launched the Historikerstreit (“Historians’ Dispute”). It was then that he could introduce his central argument published in the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung with an article titled, “The Past That Will Not Pass Away.” In his book In Hitler’s Shadow, Richard Evans summarizes the arguments as follows:

With the passage of time, [Nolte] said, most events tended to lose their urgency and became the object of quiet and scholarly study by historians. Not so the events of the Third Reich, which continued to hang over the German present like an executioner’s sword. The Third Reich was, he said, constantly held up as a negative example of militarism, even though in the Federal Republic [of West Germany] everyone now at least claimed to be a pacifist; of austerity, even though the Federal Republic was now a highly prosperous society; of male chauvinism, even though no one was now openly a male supremacist; of great-power imperialism, even though the role of the Federal Republic in world politics was now only that of a medium-sized state; of state-inspired mass murder, even though West Germany now enshrined human rights in its legislation. Yet the memory of Nazism, Nolte complained, awakened the constant fear that the old Adam would break through the surface of West German society in all these respects.

That Nolte wrote this only four decades after the end of the Third Reich and the Holocaust and was acting as if he was speaking about the ancient violence of Genghis Khan and the Mongols or the cruelty relished by the Assyrians strikes a chord of false equivalence. If one were to imagine how surviving Anushtegin chroniclers might have spoken of Genghis Khan and his conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire in the year 1261—four decades after the end of the conquest—it strains credulity to imagine them simply hunching over their parchments by candlelight, forgetting what their parents had told them about the war and the raids from their youth and the suffering they witnessed, all in service of “quiet and scholarly study.” Historical memory has a tendency to last far longer than scholars like Nolte (and those following in his footsteps) seem willing to accept. Modern media and communication technology helps keep narratives alive for more people than ever before, but it is a disservice to the written and oral traditions of past civilizations to imagine or even imply that they simply became amnesiacs of their own suffering as soon as it was over.

Nolte was engaging in something more in his true wheelhouse—that is, philosophy—that struck me as a bit sneaky. The trick was that Nolte was essentially making one reasonable claim—that the moral urgency of historical events, including atrocities and evil, naturally fades over time—in order to make a more problematic one—that because it is normal, we should accept and embrace it as a historical framework. It should be obvious, but this is a classic naturalistic fallacy. This is not to say that historians must commit themselves to calling out evil, but Nolte’s stance does seem to pervert the incentives in such a way that makes excusing or even celebrating evil far more likely for those looking to do so. This was not Nolte’s goal, by any means; his goal was more associated with re-establishing lost German national pride, as we will see later. As Evans explains:

Nolte implied that [this fear of the German past] prevented West Germans from identifying positively with the state in which they lived. He sought to remove this obstacle with a variety of arguments. It was time, he said, to recognize that the historical reality of Nazism was complex as any other historical reality: time to put away the black and white and start painting in the shades of gray.

Nolte followed his own advice the following year with the publication of The European Civil War, which crystalized his complaints and assertions that he had made in his original essay from 1986. He built upon the themes established in his original essay, most significantly including the idea that the Final Solution was not, in fact, unique (thanks to examples like the Armenian genocide of 1915-1916, the Soviet Union’s Gulag Archipelago, and, in a much more strained comparison, the United States’ Vietnam War). Not only this, Nolte’s most potent claim, and one that seems to possess the most sticking power even to this day, was that the true essence of National Socialist ideology was “neither in criminal tendencies nor in anti-Semitic obsessions as such,” but rather, “in its relation to Marxism and especially to Communism in the form which this had taken on through the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Revolution [of 1917].” In other words, Nazism was only as radical as the victories of Soviet Communism essentially forced it to be. As Evans puts it, “the crimes of the Bolsheviks […] took on such dimensions in the 1920s that they called forth a defensive reaction on the part of the bourgeoisie,” thus making Hitler’ and the Nazis’ violent opposition to communism, in Nolte’s words, “understandable, and up to a certain point, indeed, justified.”

Putting aside the undeniable truth that the Bolsheviks’ reign of true terror began almost as soon as the Russian Civil War ended in 1922 and only managed to intensify in horrific magnitude over the next decade and a half, the notion being pushed by Nolte that this was the raison d’etre of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialists is a pseudo-clever bit of historical revisionism. It plays with the truth—namely, that communism constituted a natural threat, both to German conservatives and liberals alike, as well as democracy itself, but elides the fact that Hitler’s radicalism was no less violent and threatening. This revisionism is employed in a very familiar way as we will see, completely absolves Hitler and the Nazis of having any real agency. As Evans summarizes:

The Nazis needed an ideology to defend Germany and the bourgeoisie against the Communist threat. Antisemitism provided such a counter-ideology. It was thus essentially a product of anticommunism, and Hitler’s “Final Solution” was a copy of the Gulag Archipelago in everything except the detailed procedure of gassing. […] Thus Nolte seeks to rehabilitate, or at least to excuse, the Germans, the Nazis, the bourgeoisie, and fascism in general by portraying Hitler’s policies as a defensive reaction to the Soviet and Communist threat. Violence, he is saying, always comes first from the left. Nazism was basically a “justified reaction” to Communism; it simply overshot the mark.

Where I somewhat part with Evans is that I believe it is important to point out that there is an aspect of truth to the idea that “the left starts it,” in the context of violent escalation, as could often be seen during the German Revolution of 1918-1919. But the reverse can be true as well, as seen in the absolutely brutal and savage behavior of the far right Ustashe movement in the Independent State of Croatia, leading to twin backlashes from the royalist Serb Chetniks and the Communist Yugoslav Partisans that created the Yugoslav Civil War of 1941-1945. This to say that pointing these things out—that “they started it,” whoever “they” might be—carries very little moral valence outside of an elementary school playground. No one “side” is innocent of this dynamic because this dynamic is a human one that transcends ideology. Therefore, while I do not fully subscribe to Evans’ own attempts to somewhat downplay the radicalism and violence of the German left during the Revolution, I do think it is clear that his characterization of Nolte’s views as essentially and morally bunk is largely correct.

Nolte took his revisionist approach a step further by even going so far as to justify Operation Barbarossa as being, in his words, “preventative,” because—and this strikes me in some ways as the most outlandish claim of all—Stalin had been declaring “mental acts of war” against Germany. I was initially uncertain as to what a “mental act of war” even is, but it became clear (with the help of Perplexity AI, I must admit) that this was simply Nolte’s turn of phrase for what we now commonly call a “psy-op,” a favorite term of conspiracy theorists everywhere. Obviously psychological operations exist, and have existed for a very long time, and it would be naïve, or even dishonest, to believe or claim that German Communists had no connections to the Party in Moscow. Despite early ruptures within the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD) over split loyalties between Stalin and Grigory Zinoviev after Lenin’s death in 1924, they absolutely did have direct ties to the Kremlin and were seen as the most significant force for communism outside of the Soviet Union. However, even if Stalin had declared “mental warfare” on Hitler, that does nothing to prove Hitler did not have his own plans for the lands to the east that had little to do with defending Germany from the encroachment of communism. We should not have to relitigate Hitler’s vision of a Drang nach osten yet again to show why this claim of “justifiable” defensiveness is, frankly, silly.

However, as stated above, this claim of understandable Nazi defensiveness possessed sticking power, and received an even bigger shot in the arm than from the likes of Ernst Nolte. In 1989, a now-infamous book was released titled Icebreaker: Who Started the Second World War? written by an ex-Soviet GRU officer named Vladimir Bogdanovich Rezun, more famously known as Viktor Suvorov, who defected to the United Kingdom in 1978. Like many ex-communist defectors to the West, both then and now, he became a bit of a sweetheart to Westerners on the far right, since he was willing to confirm just about anything that terrified them about the avatar of leftist hobgoblinery, the Soviet Union. According to Suvorov, the Soviet Union had been preparing for a war of conquest since the 1920s, claiming that under Stalin’s proposed Five Year Plans in which Soviet society would become collectivized, then industrialized, and then finally, militarized, allowing them to ultimately attack Nazi Germany from the rear in July of 1941. Suvorov claimed that Hitler became aware of this plan and, justifiably, invaded the Soviet Union as a pre-emptive strike against this flagrant act of communistic imperialism.

While it is undeniably true that Stalin saw opportunities in spreading Soviet-style communism across the world, especially after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, the evidence presented by Suvorov has not survived scrutiny. For example, Suvorov’s main claims of Soviet plans for an invasion to the west in July of 1941 were “supported” by very dubious sources. The only primary sources that even come close to supporting the idea of a preemptive strike by the Red Army are claims made by German generals, and only after the war was over. It is of course understandable that the last thing a Soviet defector would do is trust the word of anyone within the Soviet government, but that does nothing to make the former military leaders of Nazi Germany any more trustworthy when it comes to this question.

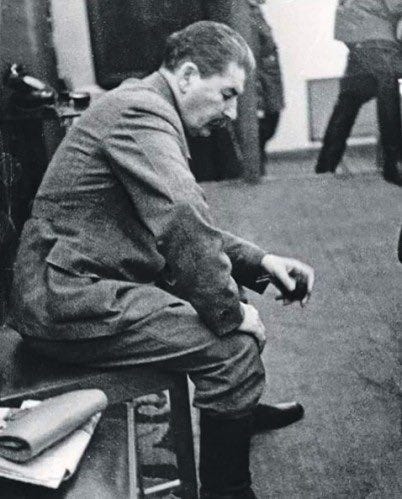

However, it is the circumstantial evidence that tends to get the revisionist juices flowing; namely, the Soviet military build-up during the 1930s, as well as the concentration of Soviet armies on the western frontier, all in the context of Stalin’s following statement alleged by Suvorov to have been made in 1925:

Struggles, conflicts and wars among our enemies are our great ally and the greatest supporter of our government and our revolution […] If a war does break out, we will not sit with folded arms—we will have to take the field, but we will be last to do so. And we shall do so in order to throw the decisive load on the scale.

On its face, this appears to be compelling evidence. However, while the traditional view of Hitler’s surprise attack that dominated the main narrative of World War II has been convincingly nuanced, the fact remains no one truly knows what Stalin’s plans actually were on the eve of war and the reality seems to be that these pieces of circumstantial evidence can be explained without placing motives within the Soviet dictator’s head that cannot be proven or disproven. As historian Alexander Hill has pointed out, the build-up was less about creating a powerful invasion force that would take advantage of the capitalist powers destroying one another, and more about creating a defensive force against the obvious threat Hitler had become by 1940 when the Wehrmacht ran rough over France. Stalin was notoriously careful and did not trust anyone—much less a figure like Hitler—as far as he could throw them, but he also saw little value in igniting a war with the Nazis even one second before his own military—to say nothing of his own people—were ready, which he did not believe—at least in 1941—that they were. In his 2015 analysis, historian Evan Mawdsley explained as follows:

Stalin and the Soviet high command were aware of the scale of the German build-up, but they believed they had matched it and that the Red Army could deal with an invasion, if it came to that. […] Stalin knew that large German forces had been deployed along the Soviet frontier. What he did not know was what Hitler intended to do with them, and he made a fatal misjudgement: he assumed that there was no plan to attack Russia in the near future. Stalin’s key assumption was perhaps that German policy was undecided, but that rash Soviet action could bring about an unnecessary, or at least premature, war with the Reich.

Mawdsley also points out that Stalin’s view indeed seems almost cartoonishly naïve, but that this view—the one pushed by Suvorov and those who have followed in his footsteps, but also scholars like Nolte—is completely divorced from the reality on the ground and at the time and almost certainly informed by hindsight. The truth was, the Soviets faced several internal challenges when it came to understanding the intentions of Hitler and the Nazis; “some logical, some not,” in Mawdsley’s words, which “prevented a proper reading.” Laying these challenges out, Mawdsley writes the following:

To start with, the decision-making structure in Moscow was over-centralized. A great deal depended on Stalin’s personal judgment. Accounts vary, but it appears that the Soviet high command did not receive all of the information that Stalin and key Politburo members did. It has also been argued that the information and assessments sent to Stalin were tailored by Golikov, the head of military intelligence, to tell the dictator what he wanted to hear. Much came down to Stalin’s personal view. Of course, we do not know what Stalin thought. As an old man, [Ambassador Vyacheslav] Molotov correctly urged caution on this subject, in a critique of other veterans’ memoirs of the war: “‘Stalin believed this, Stalin thought of that.’ As if anyone knew what Stalin thought about the war.” It would seem, however, that Stalin was both cautious and suspicious. In the background was his perception of the German power structure. Stalin may well have believed that the leaders of the Third Reich were divided between those who wanted immediate war with the USSR and those who did not, and he may well have placed Hitler in the latter group. Stalin’s key assumption was perhaps that German policy was undecided, but that rash Soviet action could bring about an unnecessary, or at least premature, war with the Reich.

Other explanations are provided, both by the historical record and by historians such as Mawdsley. The Soviet ambassador to Washington, D.C., responding to the reliable intel about Germany’s Operation Barbarossa plans, articulated what was likely the thinking at least around Stalin, which was not that he trusted Adolf Hitler, but that he did not believe the German dictator would be so foolish as his Kaiserreich predecessor in starting another war on two-fronts; “I consider the most likely time for the beginning of action against the USSR,” Ambassador Golikov said, “to be immediately after victory over Britain or the conclusion with her of a peace acceptable to Germany.” This was supported by Stalin telling the famous General Zhukov shortly before the commencement of Operation Barbarossa that “I believe Hitler will not risk creating a second front for himself by attacking the Soviet Union.”

None of this is to say that Stalin and the Soviets were not weighing the possibility of engaging with Nazi Germany before Operation Barbarossa was unleashed upon them. They almost certainly were, knowing as they did what the Nazis thought about communists. But Stalin, unlike Hitler, was far more patient and pragmatic as far as totalitarian dictators go, and understood the limitations of his own empire’s ability to mobilize in a way that made any sort of sense in the context of spreading communism by the point of a rifle to the western world, so say nothing of going to war with the seemingly unstoppable Third Reich, whose only real enemy by early 1941 was Great Britain. Stalin was aware of this because he had been the one to weaken his own empire and make such a plan ludicrous. As Richard Evans explains:

Specialists on Soviet history seem agreed that the USSR had been gravely weakened by the successive purges unleashed by Stalin during the 1930s. Something like two-thirds of the higher-ranking officers of the [Red] Army had been killed or otherwise removed from office, including three out of five marshals, sixty out of sixty-seven commanding generals, all eight senior admirals, and vast numbers of other senior military personnel. Moreover, the purges affected a substantial part of the management of munitions, transport, communications, vehicle, and other industries, as well as removing large numbers of skilled workers from these and other areas. Not surprisingly, the British government and its military advisers regarded the Red Army as hopelessly demoralized in 1939. Stalin was well aware in 1941 that it was in no condition to launch an attack on Germany; and the experience of the first months of the war was to prove the point in the most dramatic fashion, as thousands of square miles of Soviet territory and millions of Soviet troops fell to the German invader.

This is all well and good, a fan of the Icebreaker narrative might say. But how could the Nazis have possibly known this? The Germans clearly understood that there was something to fear, what with the obvious threat world communism posed; Stalin’s purges were examples of this! And let’s not forget the Holodomor, and all of the violence that occurred at the behest of Vladimir Lenin! And that is true; the Nazis were indeed well aware of these crimes. But that awareness of what was happening behind the prototypical version of the Iron Curtain did not suddenly stop with the threat Stalin and the Soviets posed thanks to their brutality (whose ruthlessness Hitler did indeed admire). They were well aware of Soviet weaknesses as well. As Evans continues:

Just as important, however, was the fact that Hitler and his generals were also aware of Russian weakness at this time. They did not expect any serious opposition from the Russians, still less a general offensive. Through 1940 and well into 1941, the Nazis were thus able to concentrate the overwhelming mass of their troops in the West for the invasion and subjugation of France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, and Norway. In all the records of Hitler’s military conferences and discussion, there is not the slightest hint that he feared a Russian attack. […] It did not suit the purposes of Nazi propaganda, still less the need to motivate the troops, to advertise the Nazis’ and the German Army’s knowledge of the weakness of the Red Army. To convince the troops of the need to fight, their commanders asked in 1941, during the early months of the invasion, “What would have happened had these Asiatic Mongol hordes succeeded in pouring into Europe, and particularly into Germany, laying the country waste, plundering, murdering, raping?” […] But, with the well-known cynicism of the Nazi propaganda machine […] all this was very far from the actual assessment of the Red Army’s strength arrived at by Hitler and the leading German generals in private.

Thus, the only “evidence” that the Nazis somehow intuited Soviet intentions—which were not even clear based on the evidence we can gather now—is the ideologically-driven paranoia that they possessed. Evans points out that the Goebbels diaries suggest that the Nazis believed the Soviets were waiting for the right moment to strike—namely “until all sides were exhausted,” in Evans’ words—and as we have seen from Mawdsley’s assessment of Stalin’s record, that was certainly possible. However, there is no way that the Nazi leadership knew that. It was all speculation and thus cannot be taken seriously; post-hoc justification is not justification for believing something without evidence at the time of believing it. This of course does nothing to absolve Soviet communism’s rapacious character—again, something we know all too well today—but if we are to put ourselves in the shoes of someone who only knows what Hitler and the Nazis knew, it is all but impossible not to come to one conclusion: they only had their prejudices, fears, and not much else guiding them. That, and, we should not forget: a long-held mystical claim to the lands of the east about which the Fuhrer had been fantasizing since at least the 1920s.

The Icebreaker thesis, like that of Ernst Nolte’s own theses about the lack of uniqueness of Auschwitz or the Nazis’ extermination of the Jews (and their millions of other defenseless victims), might sound strange, if not outright disturbing, to a lot of you reading, especially since they found a certain respectability in historical debates many, though not too many, years ago. And indeed, reading these claims—especially those that downplay the evil realities of the Third Reich, right down to their use of extermination camps—can make one’s stomach understandably turn. Why would anyone go so far out of their way to try and contextualize something in such a way that essentially scrubs the self-evident grime that Nazism created? How could it be anything but secret neo-Nazism or outright Holocaust denial? After all, Nolte, Suvorov, and others in their milieu have achieved significant audiences among the far right, including neo-Nazis and Holocaust deniers.

The first thing worth mentioning is that this latter point—one that I have seen be made more than once—is simply a guilt-by-association fallacy. A writer can no more control the make-up of their audience than a human can train a fish to climb a tree, and it’s beyond silly to demand either. But the second, more important thing, is that this was never the deeper goal of Nolte and his compatriots. Suvorov’s own motives are obvious enough, given that he was a defector from the country he sought to profoundly villainize more than was necessary in order to demonstrate its obvious villainy. But as mentioned earlier, in the case of Nolte and the other German historians who generally agreed with him, it was more about German national identity and purpose; typical nationalism, in other words.

Another celebrated historian of World War II and the Third Reich, Ian Buruma (who did the profile of David Irving for The New Yorker, as a fun coincidence), wrote on this subject as well in his book, The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan, in which he described one of the central issues of the Historkerstreit to be “the spiritual vacuum and loss of national orientation in West Germany.” As Buruma explains further:

Nolte, [Michael] Stürmer, and other conservative historians argued that Auschwitz should not be allowed to drive a wedge into the continuity of German history. For history must provide a nation with an identity—spiritual, political, aesthetic. Germans must be able to identify with national heroes, even, in the opinion of one famous historian Andreas Hillgruber, with the common soldier of 1944, defending the German homeland against the Communist hordes.

The intentions, as we can see, were largely nationalistic. The key thing, however, is this: while intentions certainly matter, it does nothing to the morality of the claims actually being made. In fact, it shows skewed priorities at work, which gives an impression of callousness at the absolute best. Because nationalist history—not national history, it must be noted—is not history at all; it is politics. It could even be described as religious, in the civic sense. People can and should be free to use the historical record however they want in the context of free speech, but that is not what history is for. And the fact that, as Buruma points out, German textbooks in both the East and West during the post-war decades attempted to craft a heroic identity for Germans by emphasizing the acts of resistance that did indeed exist during the Third Reich; “an identity, that is, erected in opposition to the Nazi state,” in Buruma’s words. This is certainly another facet of what is wrong with treating history as politics—seeing as emphasizing heroic resistance can be just as, if not more obscurantist to the realities of the Third Reich. But it also demonstrates that the premise from figures like Nolte—and those who follow in his and compatriots’ example—is made completely of straw.

…

This should all be sounding very familiar to those who have been following Darryl Cooper’s work and statements regarding his World War II series, either as fans or critics. It certainly struck me as such, even more so than his admission of admiring David Irving’s work. That is because many of the claims and aspects of claims made by figures like Nolte and Suvorov were resonant of claims Darryl had made long before his Tucker Carlson interview in September of 2024. Seeing them appear in print—namely in Evans’ In Hitler’s Shadow—flashed me back to several things he had said in his show, including the one time he and I collaborated, specifically on our mutual friend Daniele Bolelli’s History on Fire podcast.

Back in the fall of 2020, everyone was diving deep into podcasts, both as consumers and creators. Most of us working in the field of historical podcasting had been going at it for a number of years, but very few of us had seen much in the way of widespread success. Daniele Bolelli was one of the few and being the amazing human and friend that he is, he reached out to a bunch of us occupying the same space as him—the long-form storytellers—and brought us in for a collaborative project. What resulted was an incredible ensemble/anthology episode that included him, Inward Empire’s Sam Davis, The Dangerous History Podcast’s CJ Killmer, Our Fake History’s Sebastian Major, Darryl Cooper, and myself. What we all created ran the gamut of topics but they all shared the same theme: the ripples created by history. I highly recommend listening to it if you have not already because it is seriously fascinating stuff. Darryl’s was a fascinating look at the Japanese Red Army Faction and their role in inculcating Islamist terrorists in kamikaze values, thus giving birth to the modern suicide bomber. It was truly fascinating and does indeed check out in terms of accuracy, but in the midst of his segment, he made a passing remark about the Third Reich engaging in a preemptive strike against the Soviet Union in order to prevent the spread of communism in Europe.

I did not think much of this claim, but it sounded a bit off to me. However, I was (and still am) by no means an expert on the history of the Second World War or the Third Reich, but I was pretty confident that I had never even heard of such a claim. It was not until I heard about Suvorov’s Icebreaker thesis that I knew where this outlandish-sounding claim came from, compounded with the work done by figures like Nolte. And speaking of Nolte, when I had read more about Nolte’s views, my memory of Darryl’s work was jogged again. When I first listened to Darryl’s also very effective episode about Soviet communist brutality, “The Anti-Humans”, the year following our collaboration, I was like many people shook by what I heard, as well as deeply inspired.

However, among the many intriguing parts of that harrowing episode, Darryl’s distinction between Soviet crimes and Nazi crimes always stuck with me. I found the distinction flawed, but certainly interesting. The gist of his distinction was that the Nazis’ crimes were heinous on the face of it all, but that the Soviets’ crimes were the true basis of evil thanks to their efforts to destroy the soul; as he stated at one point, when he thought about Hitler, he really just saw the equivalent of “Genghis Khan spouting racial pseudoscience,” and when he thought about the Soviets, he saw something much more “alien.” I leave the core of this question open for the philosophers, but something else Darryl said about the Nazis never really left my memory, which was that they were essentially brutes, no different from other genocidal regimes in the past. Again, this is the same basic argument made about the Third Reich by scholars like Ernst Notle.

However, the main thing that struck me as I read Evans’ assessment, as well as Nolte’s words, was the emphasis on breaking traditional black and white narratives; this has been the defining sales pitch of “Enemy: The Germans’ War,” something about which I have spoken more than once. The impulse to cast things in shades of gray that carry a relatively simple moral valence—that is, the inherent evil of the Third Reich—is very much an artifact from the Historikerstreit, particularly from Ernst Nolte. The difference, it seems to me, is in the context of why this effort was and is being made. While Nolte seemed to be more motivated by despair at the death of a proud German national identity, it is far less clear why Darryl believes it is important for us to relitigate the German perspective, outside of his occasional comment about trying to prevent American involvement in future conflicts that will be cast in moral terms informed by what he calls the “court history” of the Second World War. In truth, this is likely something that will not be clear until the series is completed.

However, the fact remains that the context of the Historikerstreit and the context of historical podcasting/content creation in 2025 are completely different. It might have been fair, say, for Nolte to claim in the mid-1980s that the historical reality of the Third Reich was not being seen in the proper moral context. At that point, the world was very different, the field was still very young, and full access to information and differing interpretations had yet to manifest. That is why to claim that a morally simplistic context persisted in the years—decades—that followed without significant nuancing is, frankly, silly. Perhaps in the context of popular culture, one could probably make that argument; but in the context of Third Reich or Holocaust scholarship, it is simply going to come off as dishonest or uninformed to do so to anyone who is even mildly well-read on the subject.

When combined with the fact that Darryl’s intentions with this series are not particularly clear, it is not unreasonable that people will fill in the gaps with their own assumptions. While it would be nice if people did not assume the worst in others, everyone’s mileage will always vary. This remains my only significant critique of Darryl’s work on this subject thus far: that he is presenting an inaccurate premise of how the Second World War is perceived in the United States and taking issue with people assuming that someone using this inaccurate premise is doing so dishonestly (when the only alternative is that it is being used ignorantly). At the end of the day, it is simply untrue that Nazi Germany has gotten short shrift when it comes to historical scholarship; in fact, historians pushing for historicization of the Third Reich has existed for nearly four decades. As Richard Evans wrote in 1989:

[The call for historicization] involves a rational approach to Nazism rather than a simple reliance on moral condemnation. Nazism and its effects cannot be made real to people who, like most of today’s West Germans, were born long after the event, if they are presented in crude terms of heroes and villains. The nature of moral choices people had to make can only be accurately judged by taking into account the full complexities of the situations in which they found themselves. Not everything that happened under Hitler was equally evil; not everyone who resisted was equally good. German society shows many continuous developments cutting across the period 1933-45, with deeper roots in the past and with consequences stretching beyond the collapse of the Third Reich into the present. This approach has yielded many important new insights into the nature of Nazism. Far from blurring moral distinctions, as some have claimed, it makes them more precise. This is surely a gain rather than a loss for historical understanding. [Emphasis added]

Again, this was written in 1989. Thirty-five years ago. The scholarship, as I have covered before, was already expanding three years later and only became more complex and nuanced as the decades wore on. Now, Darryl might claim that this laudable goal laid out by Evans so long ago was never truly achieved and that therefore is the problem, but frankly, that feels like a “No True Scotsman” fallacy (or perhaps a “real communism has never been tried” fallacy) on its face, to say nothing of the reality. The only perspective that has not been given any real credence during this time is the one that Evans disputed in his book, and that other historians’ work has largely discredited: that Hitler and the Nazis were perhaps justified in their hatred of the Jews and/or their rapacious expansionism.

In essence, while I do believe many of the criticisms against Darryl have been mostly unfair and irritatingly dismissive, I completely understand why people continue to call him a “Nazi apologist.” At this point, there are only two avenues for him to go down:

Either he embraces the label and makes an argument that we should not blame the Nazis for creating an objectively wretched, degenerate, and violent state because they were sincere and because sincerity breeds tragedy we should feel sad.

He admits that his sales pitch for this series as breaking new ground is not as he has claimed but makes a case for why the Third Reich scholarship that has existed for decades within the dreaded mainstream is insufficient.

The first avenue will come off as dishonest and morally depraved but is more likely to be eagerly consumed by many of his listeners. The second avenue will come off as honest, but has the risk of being thoroughly discredited because he would be openly and, more importantly, directly questioning well-defined and sourced wisdom of experts. This second path would conflict with the approach he has been taking, where the clear inspirations for his approach—those of figures like Ernst Nolte, Victor Suvorov, and, yes, by his own admission, David Irving—remain unspoken and unknown. That is, unknown except to the most pedantic among us, such as yours truly.

The only question remains: why continue to write about this at all? After all, I had not planned to say much else. However, I had not yet read Evans’ accounting of the Historikerstreit and thus the pieces had not fallen into place for me about the different schools of thought that rocked West German academia within my lifetime. I also did not think that further clarity needed to be provided. However, this is not really about Darryl Cooper or his podcast as much as it is about creating transparency on the question of where certain interpretive frameworks originate. It is obvious that knowledge of the Holocaust and the history of the Third Reich is woefully inadequate as we near the centennial of the Nazis’ seizure of power. And making use of interpretive frameworks that have been almost completely discredited is not going to help paint a human face on inhuman events. Even if Darryl completely departs from this framework thanks to his ongoing research (which I doubt he will), it is helpful to know where more provocative frameworks came from. This is because today, credentialism is out; thus, revisionism is in, as has been made clear by the multitudes of people for some reason still talking about the debate on Joe Rogan between Douglas Murray and Dave Smith (especially, it seems, by Dave Smith himself).

Where I likely depart from many of the people who have convinced themselves that Douglas Murray “won” that debate is not that I believe Dave Smith “won”—I believe we all lost, if you want my short assessment. Where I part company with people like Murray is with the idea that revisionism is “dangerous.” Not only do I believe that this is a silly framing on free speech grounds, but I also recognize that revisionism has always existed, including about the history of the Third Reich and the Holocaust. If anything, this essay should have made that obvious. It may be ugly to many watching or listening, but it never has not been ugly because, shocker, much of history is ugly, and people naturally do not want to get muck on their clothes. That, really, is the lesson of figures like Ernst Nolte, doing all they can to flee from Hitler’s shadow: a desire to feel clean and free of emotional burdens often leads people to believe and say things many others consider unspeakable. This is something to which all historians (or storytellers) are vulnerable.

Ultimately, it is easy to act like revisionist history is beyond the pale and a waste of everyone’s time, as if that assessment is never made with hindsight. This is an inaccurate framing of how history works. Sometimes, at its best, revisionism can unveil something that has never been considered before. Based purely on what we have seen so far and based on the apparent influences, I do not believe that will happen with what Darryl Cooper’s project or with anyone who follows in his footsteps. However, I do stand by his attempt because at the very least, it will be interesting). Even at its worst, revisionism can sharpen the arguments of those who dissent from the revisionism. Or, at least, those who care enough about accurate history to try.

He goes far beyond "humoring". He straight up agrees with paragraph long denunciations of the Evil Jews and their century-spanning conspiracy to corrupt and destroy Western civilization, with the very light push back of "nevertheless, it's harmful to let yourself be consumed by hate".

Really sorry to follow you around from article to article, but you really need to include in your historiography of Daryl Cooper the possibility that he really really doesn't like Jews as a motivating factor for all this. It would take you less than a half hour of browsing his comment section to find pretty strong evidence to that effect; certainly less time than reading Evans.

I'm only bothering you because you're one of like, 5 people on earth who are willing to critique Darryl seriously and fairly.