Over the weekend, I was surprised to see my name appear in the New York Times.

Let me nuance this a bit. I was not surprised to see it appear. First, because this was the profile they did of Darryl Cooper, host of the Martyr Made podcast, and I have made no secret that I’ve known Darryl for some time now, both personally and professionally, and consider him a friend with whom I frequently disagree on certain historical and political matters. It was also not surprising that he was given this profile treatment, since has found himself appearing in the news periodically for the past eight months or so, ever since his now-infamous Tucker Carlson appearance in September 2024. This attention was reignited again with his Joe Rogan appearance in March 2025, and again, though in absentia, on Rogan’s podcast in April 2025 in which the paleolibertarian-adjacent comic Dave Smith and the neoconservative writer and commentator Douglas Murray debated the merits of hosting figures like Darryl. Finally, it was also not surprising because Darryl reached out to me privately and let me know that I would be making an appearance in the article.

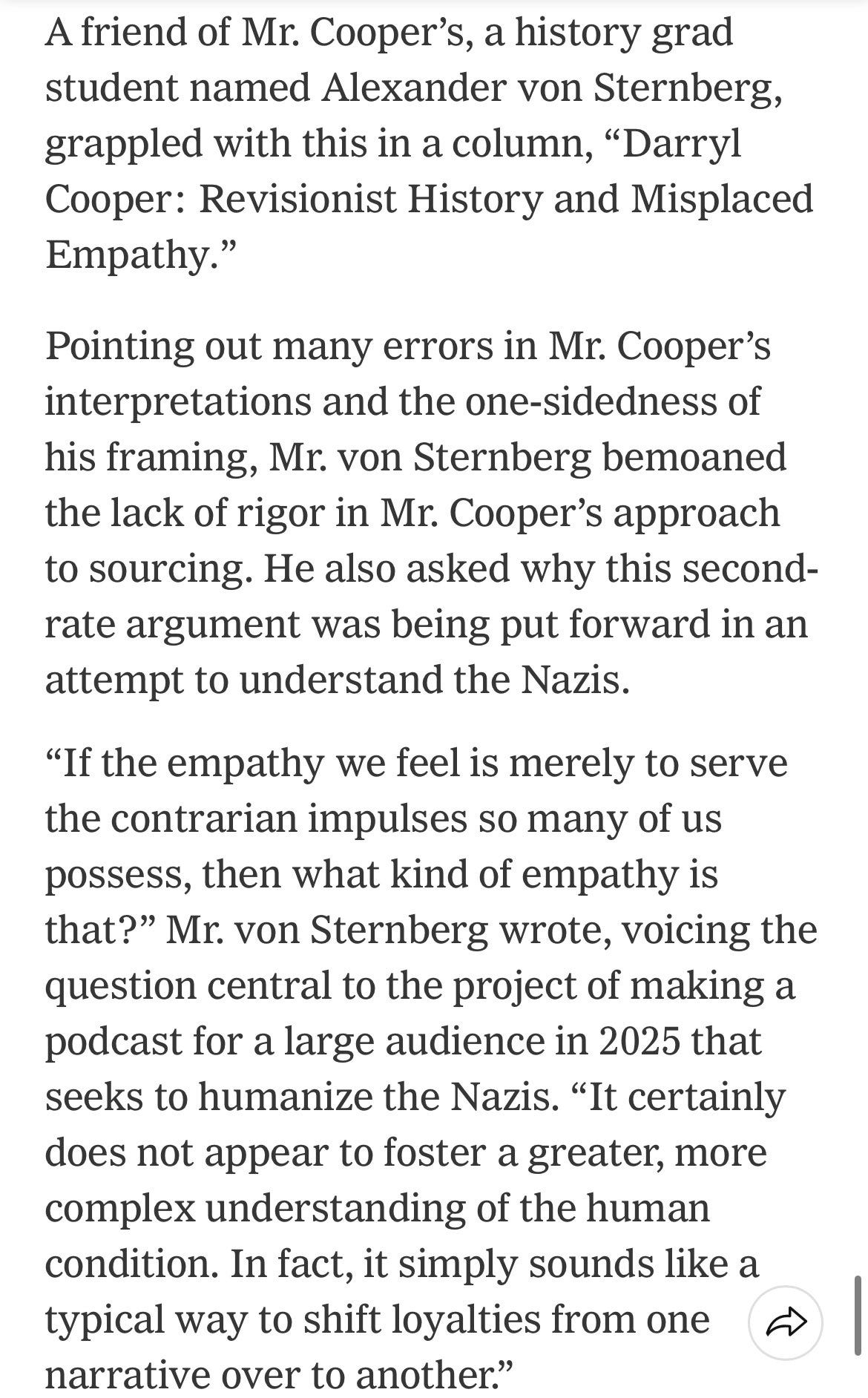

What was surprising was that the article ended with the quote appearing in the image above, something I (and possibly Darryl) had no idea was going to happen, and which adds layers of significance (for my ego, of course) and meaning (for my words that were used) that I also did not expect. The quote they used was an excerpt from my lengthy, hopefully-good-faith rebuttal to Darryl’s original comments on Carlson’s show and follow-up posts on X and Substack, published in Merion West back in September 2024 (and that I adapted into a special episode of the podcast shortly thereafter). My writing has been published in various places, something for which I’m always grateful and is something I will continue to do, but to see my words appear in the New York Times is something I won’t pretend doesn’t make me swell with pride. It also made me raise an eyebrow, given the selection of my words and their placement, which in turn got me thinking about how we all—history podcasters and historians included—make use of other people’s words.

By placing my words at the end of the piece, the author Joseph Bernstein (by all accounts a good and fair journalist, and one who Darryl believes did his best to be fair in his characterizations) is essentially letting me have the last word, but the last word as he (and no doubt his editor) defines it. This is without a doubt a major privilege for which I am grateful, and yet, there is something a bit odd (or perhaps “off”) when you see your own words being used to convey a meaning that you did not initially intend. In using the passage as he did, Bernstein seemed to be suggesting that I believe Darryl is trying to make us shift our loyalties toward the Axis powers in general, and the Nazis in particular. The first important thing to point out is that in my original essay, I made it clear that I did not think impugning motives was helpful.

The next important thing to point out about my original essay is that I never intended to imply that Darryl was trying to make his audience (or the wider public) shift their loyalties at all. I was simply saying how it often comes across, especially as a first impression and to people who do not know you or your work, particularly when one selectively applies agency and empathy, especially with the vilest of historical figures like Adolf Hitler. My broader point was that I see that as an exercise of politics/polemics rather than history, a la Howard Zinn. I also wanted to make it clear that I believe diving into historical empathy itself is problematic no matter who does it because I believe it’s a problematic way to look at the world in general. Empathy not only has limitations but it creates moral hazards that, to my view, simply are not worth the price of admission. Thanks to this bias I have, I would rather be accused of being callous than accused of being selective with my empathy; Darryl believes differently, and I will always respect him immensely for that.

With all of that said, I begrudge no one on these admitted nitpicks of mine, least of all Bernstein or his editors. This kind of use of quotes is what newspapers and writers always do and using my publicly-facing words is perfectly fair game. As anyone who follows us knows, both Darryl and I do it too, as do all historical podcasters. And here is a dirty secret that you don’t even have to attend grad school to discover: “real” historians also do this in their work. In other words, it is normal, and perfectly acceptable as long as the meaning of the words themselves is not distorted beyond recognition. When it comes down to it, I am obviously happy to see my name appear in the “Paper of Record,” and I do think this could have been far less charitable to Darryl (especially in comparison to the earlier reactions to his work and the rise of the weird and, in my opinion, pretty ham-fisted “woke right” aspersion we tend to see online). Had this article been one that just regurgitates the low-resolution claim that he is a “Holocaust denier,” I would have likely felt much differently.

Overall, I thought the piece was very solid and provides a good enough snapshot of Darryl’s work, process, and the real and potential shortcomings of those two things. I have already made my position on these things clear, especially since it has become clear that Darryl is using David Irving as a source (but by no means as his only source). But I also do not believe that Darryl’s project is a bad idea; quite the opposite. With that in mind, I am going to say something that could well alienate at least a few people among the handful kind enough to read my ramblings: there is nothing inherently wrong with humanizing Nazis. I say that because there is nothing inherently wrong with humanizing communists, or Islamists, or Zionists, or black nationalists, or American slave owners, or whoever you want to use as an example. It all depends on how you do it, and more importantly, how you make your case for why it should be done. Everyone has limits; I will never humanize Oskar Dirlewanger, for example (as listeners will know when the next episode of The Muslim Nazis is released). I see little reason to humanize serial killers like Ted Bundy, or Peter Kurten, or Randy Kraft, who clearly all did horrifying things because they wanted to and because they enjoyed themselves doing them. The fact that all of these figures were once sweet, innocent little children means less than nothing to me. If that makes me simplistic in my moral framework, so be it.

Humanizing the Nazis broadly speaking, however, is not beyond the pale; historians have been doing it for decades to varying levels of success, as I have covered. In fact, that really is the only core issue I have with Darryl’s current project, which is that he has been presenting this as something that just isn’t done or is “not allowed.” It has been done, probably with the most powerful example being Christopher Browning’s oft-cited (including by me), Ordinary Men. However, there are plenty of other books by celebrated and underrated historians alike that have sought to do just this because they understand what the distinct minority (perhaps even non-existent group) of Third Reich scholars who still, for god knows what reason, might follow the example of a hack like Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, do not: we are all human beings and thus are all equally capable of doing the most evil things human beings can do. The probability that we will or we will not based merely on vague notions of supposed cultural history is far too slippery and insanely problematic, at least for anyone concerned with the dignity of people as individuals.

This gets into my main problem with Darryl’s approach to his new series thus far, apart from doing some sweeping for David Irving over on Twitter/X: that is, his marketing of the work as something ground-breaking or even “dangerous.” In the series’ first episode released near the beginning of 2025, he invoked the idea of the “court history” of World War II more than once, and even months later, I still struggle to know what he is talking about. Apart from the aforementioned Goldhagen, there has not been much in the way of performative condemnation or black-and-white depictions of good and evil from Third Reich historians, popular or academic, in the United States or elsewhere. If he is reflecting on the sorry state of history education in the United States, particularly about the Second World War and the Holocaust, then I would be right there with him; I have certainly wasted no effort or time discussing that sore subject. But that does not appear to be part of his thinking, at least not as it currently appears. So far, the project seems to be more akin to starting a trash fire and pointing out that fire can be a creative force as well as a destructive one. We all know that, people have been discussing it for years; so why is setting the fire necessary in the first place? The case has yet to be compellingly made.

This is where the importance of clear citation and appropriate quoting comes into play. In my original piece for Merion West, I pointed out a number of errors made by the main sources Darryl had been citing—that is, Pat Buchanan and Nicholson Baker—that had to do with their use (or misuse) of quotes in their work. While we must all be selective with the quotes we use, lest we start using entire chapters as block quotes, it is extremely important that the words quoted are as close to what the author intended as possible. In the case of Baker and Buchanan—and by extension Darryl—many of those quotes omitted context that literally changed the meaning of the original sources. This did not happen to me in the case of the New York Times story, but it came close enough that I found it somewhat ironic that Bernstein was quoting an essay I wrote in which I very stridently spoke out against doing such a thing.

Selective quoting, again, is perfectly normal and acceptable, but it needs to be paired with transparency, which is something that I consider very important if you are going to discuss history professionally. I don’t particularly care whether Darryl is an “expert” or not, which was the main point of contention during the Douglas Murray v. Dave Smith debate on Joe Rogan when it came to the subject of Darryl. I just care that he is as accurate and transparent as possible. This is the root of where I actually am troubled by his use of David Irving as a source. While he is certainly free to use Irving, and seemed to be quite overtly inspired by Irving’s book Hitler’s War in the prologue, the fact that he hasn’t been open about it on the show is what strikes me as most problematic. To be fair, citing Irving is a morally loaded thing to do and it requires one to get deep in the weeds on his qualifications and lack thereof, which is honestly a podcast in and of itself. And if Irving comes up later in the series, I suspect—hope, really—some time will be devoted to that very subject, especially since . Because if it’s not, well, that is going to rub even more people the wrong way. Selective quoting is one thing, but unaddressed inspiration is quite another.

However, this—that is, historiographic critique and debate—is what, in my opinion, we should all be striving for (that is, those of us talking and writing about history for a living). Darryl isn’t inclined to do debates, and that is fair enough; I don’t particularly like them either. But one doesn’t need to debate in order to engage with the material—even problematic material—in a critical way, figure out what is true and false, and really explore the morally gray areas of our past (such as Allied fire-bombings of Axis powers, to name one of the best examples). One doesn’t have to come to the same conclusions as past scholars, but acknowledging the debate that is occurring between the sources—or between you and the sources—is in some ways one of the most rewarding things one can do when engaging with history. It’s the best way to have your cake and eat it too as a polemicist and historian or history communicator. It also separates the wheat from the chaff when it comes to one’s audience.

I suspect that at some level Darryl recognizes this, thanks largely to an unexpected but refreshing house cleaning post that he put on his Substack the same day the New York Times article dropped. He made a very compelling case for why he wants to see the good in the more reachable people falling for the trap of rank, obsessive antisemitism—it reminded me of his namesake Daryl Davis, who has done a lot of good work to deradicalize white supremacists in this country. But he also made it very clear that those low-IQ vulgar antisemites (to use his words) can kick rocks and not use his platform to drag everyone into their miserable existence. To me, that is worth applauding. But he also said that he was tired of talking about this subject. I don’t blame him; it’s a tiresome and gross subject, and it’s much more rewarding to talk about history. Whether or not it is good history or bad history is something we will only know in the future.

I look forward to it either way.

I’ve enjoyed Dan Carlin and Darryl’s work for a very long time. I view their work as a 21st Century version of oral history. When I listen to Darryl’s storytelling I appreciate how accessible it is to the average listener. This is good quality and allows those to learn broad historical narratives. However, I also have serious disagreements with some of Darryl’s interpretations of history. This largely stems from my background from grad school at an elite University. Darryl’s medium is inherently restrictive and relies on narratives of mainly first person resources to build out a story. This in itself is fine, however it is also susceptible to the same flaws of myth building and narratives Darryl sometimes complains about. The main issue I see is Darryl creates his narrative somewhat isolated and then seems to think the accepted historical narrative is wrong vs built over time by those that dedicate their lives to historical study. Darryl hasn’t found a new thread of thought, but highlights an area that professional historians have studied but discount or deemphasize based on evidence from holistic research. The other area that confounds me about Darryl is his desire to pick fights on social media. He’s very talented and quite frankly should be above that, but isn’t. It’s like a talented prize fighter getting bar fights.

It sounds like sloppy/borderline deceitful historiography is the only serious issue you have with Darryl. What are your thoughts on the fact that he fully agrees, in his own words, with multiple people in his comments section who believe that the Jews are a malign influence on the word who are responsible for most of the bad things that have happened to the US in the last century and the Western world writ large?

Not that these opinions mean you have some obligation to drop him as a friend or denounce him, but it should surely color your view of his historical commentary and narrative..

For myself as a Jewish listener of his, I am still able to enjoy his work where it touches upon Jews as a sort of anti-Jewish steelman that forces me to think through my understanding of history more carefully, and where it doesn't really interact with Jewish people (like his Aztec episode or the Jonestown series or the labor rights series) as just a good yarn that leads me down different historical rabbit-holes and the addition of dozens of new books to my thriftbooks wishlist.

But as someone doing critical analysis of his work, this really is something that needs to be confronted and integrated.