Christopher Nolan is one of the few remaining filmmakers who does nothing in half-measures. This is made clear with his insistence on using practical effects whenever possible (including the famous hallway scene in 2010’s Inception or the plane hijacking sequence in 2012’s The Dark Knight Rises) as well as his insistence on using only celluloid when filming, often in the expensive 70mm format. In his most recent film, this summer’s Oppenheimer, he seems to have finally found his groove, both for his full-measure approach and for the results we’ve seen. I managed to catch Oppenheimer in one of the few theaters in the United States equipped with a proper 70mm IMAX projector, at the TCL Chinese Theater in Hollywood, no less (a place I somehow managed not to see a film in until now, almost a decade after moving to Los Angeles). Seeing dozens (if not hundreds) of wide shots in 70mm did indeed make an incredible difference. I can confidently say that, perhaps apart from the aforementioned Inception, Oppenheimer stands as Christopher Nolan’s true masterpiece. It is probably one of the best, most piercing historical dramas I’ve ever seen, joining the ranks of Saving Private Ryan, The Pianist, and HBO’s Rome.

Tempting as it is to simply dive into a proper review of the film for its cinematic and storytelling achievements (the camerawork has no equal, the performances are as good as performances get, and the characters are, especially by the standards of 2023 Hollywood, profoundly complex), there was something else about seeing this film, and paying attention to the discourse surrounding it leading up to my viewing, that I feel like is worth dwelling on. This is because it revisits the very first historical debate I remember ever taking part in, in a classroom setting. As I jokingly put it on Twitter, what little actual formal historical training I received during my undergraduate years was partly dedicated to this debate. The debate centers on not the development of atomic weaponry, but its use. Namely, its use on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I have extremely fond memories of us spending the first week of American History 1945-2005 discussing the different motivations behind the decision and weighing their likelihood as well as their moral and historical implications. Unsurprisingly, when analyzing President Harry Truman’s decision to use an arguably still-experimental weapon on human beings, there is no consensus on why things were done as they were. But there are many hypotheses worth exploring, especially since there seems to be a particular narrative being spread, mostly on progressive Twitter (or X, or…whatever).

To give as short a version as possible, both in the last couple of weeks and many years before, there has been this notion that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were motivated by pure and simple anti-Asian racism and a desire to genocide some Orientals. This has already been challenged by people far more qualified than me, and a lot of the racism discussion has gotten even more muddied thanks to completely pointless criticisms of the film from the likes of Slate. However, it’s still a relatively common refrain (and one I wouldn’t be surprised to encounter as I enter the professional realm of history), so some criticism is requisite. This argument of racist motivation simply doesn't hold up for a lot of reasons.

The first is the simple likelihood that the U.S. would have happily used the bombs on Germany if we had them. The Manhattan Project began on August 13th, 1942, and had been in the planning stages as early as 1940—not exactly at a time when Nazi Germany’s defeat was assured. There is no way to know for certain that Germany or German targets would have been used as or passed up as targets thanks to the events of the war, but it makes very little sense to assume that German cities were off the table, given the fact that the United States’ incentive to create the atomic bomb in the first place was to do it before the Nazis did. It also reveals a fundamental lack of historical knowledge for anyone to claim that the United States was somehow tepid in its treatment of German cities. The accounts out of the Hamburg and Dresden bombings of 1943 and 1945 respectively are the stuff of nightmares, and the latter is something I’ve already covered as part of a larger story, if you can stomach it.

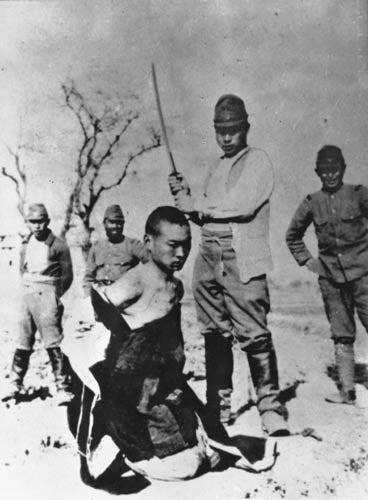

The second reason the accusation of anti-Asian racism doesn’t track is less a tactical and historical issue and more of a moral one. Because this argument is based in a pretty abstract concept with the obvious motive of smearing American war-planners—if not Americans as a whole—as virulent racists (thus invalidating any reason for them to drop the bomb that doesn’t involve the presumption of racial genocide), clearly a comparative moral calculus between Japan and the United States during the Second World War is required. And when doing this, moral comparisons fall apart very quickly. Considering the way the Japanese, using very blatantly racist and fundamentalist rhetoric to justify their objectively imperialist and colonialist actions, treated the Southeast Asian peoples and especially the Chinese after they occupied their lands, there is no question that the Japanese were the “bad guys” in the Pacific Theater. To play with moral relativism on this claim is to excuse some of the most barbaric behavior imaginable.

Speak to any Chinese person whose family survived the Nanjing Massacre about how badly American troops treated Japanese soldiers—no paragons of virtue themselves, mind you—and see how long they tolerate such moral waffling. One who wishes to minimize Japanese brutality in favor of American racism might point to our use of incredibly bigoted propaganda or, more pointedly, our heinous treatment of Japanese Americans in a literal concentration camp system. But the only thing this evidence proves is that the American government—under the beloved FDR, mind you—was a racist dung-heap in the 1940s (and in many ways it was). It says nothing about what the Japanese did or believed. And what that was, was true, pure evil. The fact is, they were just as racist and genocidal as the Germans under Hitler. It is indeed, as I said a moment ago, reductive to frame a war as simply good vs evil, especially when the “good guys” include the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin, but make no mistake: Imperial Japan was a force for evil.

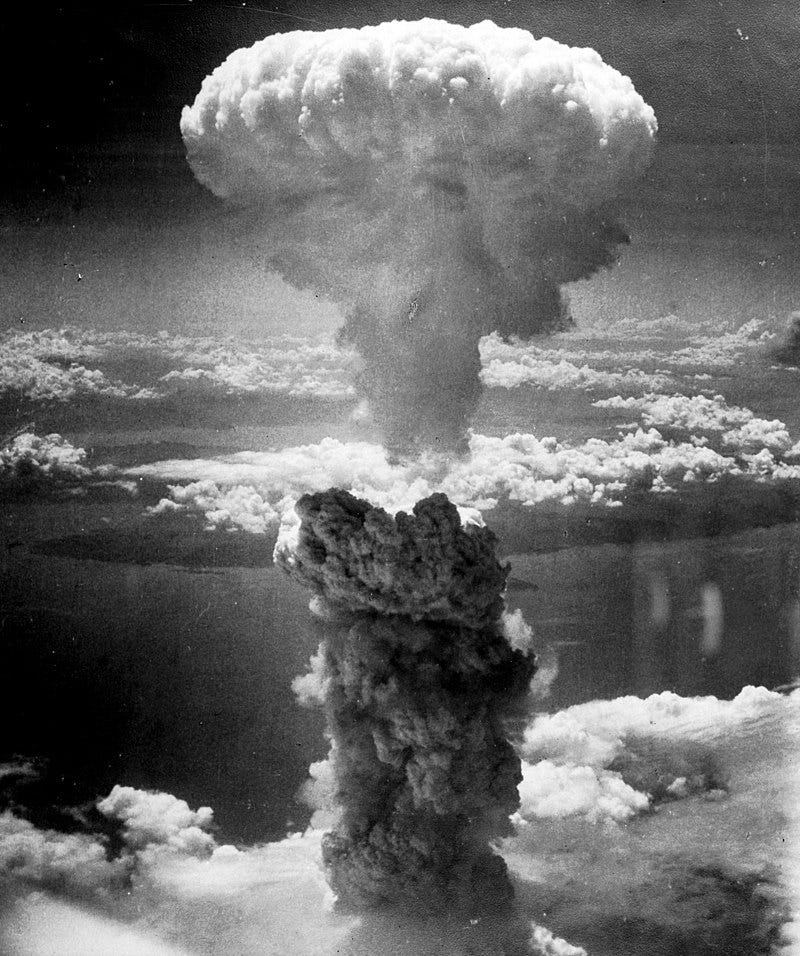

That Imperial Japan was a force for evil, however, and that the United States likely had every intention of dropping atomic bombs on Nazi Germany, does not address the central question that I was lucky enough to study in an amazing classroom setting so many years ago: why were the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Truth be told, much as I love this debate, it can be somewhat passé. However, as Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer makes clear in a much broader way, the subject is a vital one to discuss. Oppenheimer himself would be recorded saying that “we knew the world would not be the same” and, as made clear by Cillian Murphy’s Oppenheimer, we wouldn’t all understand this until we used it. And we did, on people. So we have a moral obligation to ask why.

…

It must first be noted that there are several interpretations out there regarding the United States’ decision to drop atomic bombs on Japan, twice, and while it would be fun to go through every single one, I think we’d be better suited if we simply went off my own memory of the main reasons. I have indeed checked these against other articles and material out there to make sure I’m not imagining things, but for the sake of brevity, I think sticking to the big ones that come up most frequently is probably the best way for us to move forward with this. So without further ado, let’s get into it.

The most common reason cited for using the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki is a very simple one: it would end the war quickly. It’s also probably the most mainstream historical opinion—indeed, it’s part of what’s known as the “traditionalist school”—that is put forth by many scholars, including renowned historian Robert P. Newman in his 1995 work, Truman and the Hiroshima Cult, and Robert Maddox’s own 1995 book, Weapons for Victory: The Hiroshima Decision Fifty Years Later. This view is largely accepted because it accords with many different accounts—which are dramatized in the Oppenheimer film—from people in the planning rooms. While I think it’s perfectly fair to cite this as a motivating factor, it’s also not necessarily wise to assume that anyone planning the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings knew whether this would work or not. In addition, if we’re not careful, this motive hypothesis could easily run afoul of hindsight bias. After all, we only know that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the war quickly because they ended the war quickly.

There is also pushback against this explanation by what’s come to be known as the “revisionist school,” who cite examples of Japan being ready to surrender before Hiroshima was bombed. I have an admittedly faulty memory of reading somewhere in my youth that analysis had been conducted suggesting that Japan was on track to surrender by October of 1945 thanks to resource shortages, but I wasn’t able to confirm this. Nevertheless, the revisionists claim that diplomatic feelers were being put out by the Japanese—namely through the Soviet Union, who they hoped would act as a mediator in their negotiations with the Americans. They also point to disputes within the Japanese Prime Minister’s Cabinet in the weeks leading up to the bombings, with an increasing number of cabinet members calling for negotiation, while others continued to call for war. The crucial thing revisionists claim is that Americans were well-aware of these developments—and at least in some circles they were.

U.S. intelligence had long-since decrypted Japanese code through an intel-gathering effort known as “Magic,” which was ultimately responsible for intercepting what became known as the Suzuki Telegram. And this telegram, named after Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki, did indeed indicate Japan's willingness to explore peace negotiations with the Soviet Union as a potential mediator. What these facts indicate, the revisionists claim, is that the U.S. knew full-well that they didn’t need to bomb Japan into surrendering with a still-experimental weapon and did it anyway. This is a compelling claim, but it should be noted that none of the evidence marshalled debunks the notion that the bombings were done to end the war quickly; a desire to negotiate doesn’t necessarily mean a desire to surrender, after all. But this evidence necessarily opened the door to more questions, and that’s how we get to the next potential motive.

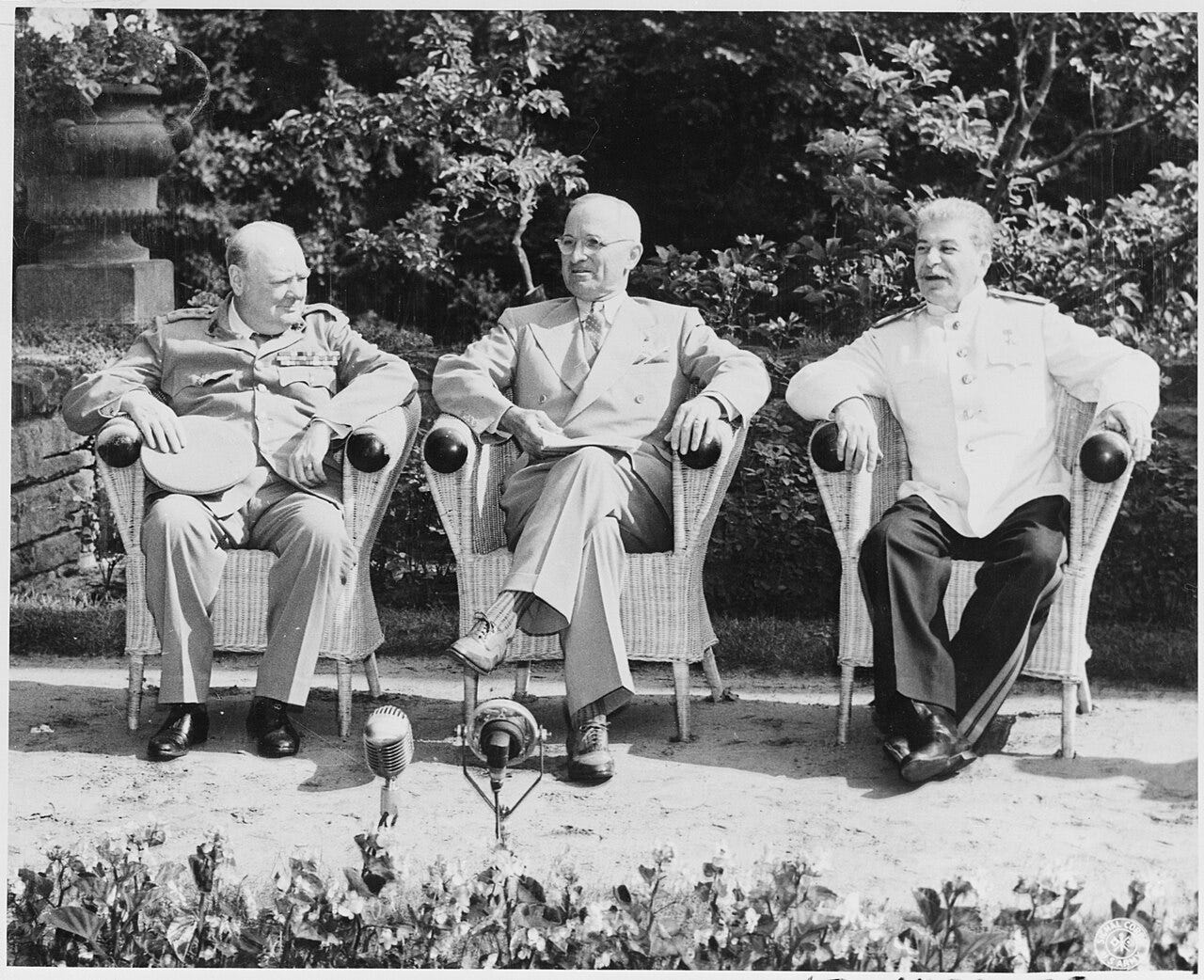

On the Atomic Heritage Foundation’s website, they have a great summary article in which they say that, according to the revisionists, “the decision to use the bombs anyway indicates ulterior motives on the part of the US government.” This allows us to ask the next most important question: what could those ulterior motives be? The biggest one I remember being discussed in my class (but that I’ve seen suggested in plenty of other places over the years) is that it had to do with sending a message to the Soviets. While there is no direct evidence pointing to this as a possible motive for detonating the bombs over two Japanese cities, there’s quite a bit of circumstantial evidence. We know, for example, that President Truman, according to his own memoir Year of Decisions, in meeting Joseph Stalin at Potsdam along with Winston Churchill, told the Soviet dictator—or rather, “casually mentioned”—that the United States had developed “a new weapon of unusual destructive force,” to which Stalin replied that he hoped the Americans would “[make] good use of it against the Japanese.” The truth is, Soviet intelligence was well-aware of the Manhattan Project by then and had known of its existence since 1941 (which actually serves as one of the dramatic focal points of sorts in Oppenheimer). Whether Truman knew this and was just feeling Stalin out or was simply passing the message along to an ally, it’s hard to say. But assuming he knew—or that anyone within the military industrial complex of the time knew—that the Soviets knew they had a weapon that would give them an edge in the conflicts to come, the detonation of the bombs over the cities could well be seen as a warning (or, to use more Eisenhowerian terms, a first move in the world’s biggest poker game that would come to be known as the Cold War).

The circumstantial evidence piles up with the fact that almost as soon as he returned to Russia, Stalin ordered his top scientists to get to work. Emeritus professor of U.S. diplomatic history at the University of California—Merced Gregg Herken, author of The Winning Weapon: The Atomic Bomb in the Cold War and Brotherhood of the Bomb, when quoted by a 2018 article written by Sarah Pruitt, would explain that “We now know that Stalin immediately went to his subordinates and said, we need to get Kurchatov working faster on this.” Kurchatov, as explained by Pruitt in that same article, “was the nuclear physicist who headed up the Soviet atomic bomb project—the Soviet equivalent, in other words, of Manhattan Project mastermind J. Robert Oppenheimer.” Kurchatov would later come to be known as the “father of the Soviet bomb,” (thanks to heading the development of the Soviets’ first plutonium implosion bomb) and certainly deserves a spot at the table of “most important 20th century figures” for that fact alone, as well as the fact that he, like his American counterpart Oppenheimer, had a change of heart when he realized just how truly devastating nuclear weaponry could (and would) be.

It’s clear that there was at least an awareness of the potential for conflict with the Soviet Union after the defeat of the Axis powers. There were certainly members of the military who very clearly wanted to continue to take the fight to the Soviets, with the famous General George S. Patton’s forces standing up against Soviet troops while on the outskirts of Prague in May of 1945. Patton was known for a lot of things, and one of them was not mincing words. When reflecting on the Soviets swallowing up Eastern Europe, he, in some pretty choice racist terms that don’t sound all that dissimilar from James Clapper or Keith Olbermann, would state the following:

“The difficulty in understanding the Russians is that we do not take cognizance of the fact that he is not a European, but an Asiatic, and therefore thinks deviously. We can no more understand a Russian than a Chinaman or a Japanese, and from what I have seen of them, I have no particular desire to understand them, except to ascertain how much lead or iron it takes to kill them. In addition to his other Asiatic characteristics, the Russian has no regard for human life and is an all out son of bitch, barbarian, and chronic drunk.”

Patton also wrote the following in his diary:

“In my opinion, the American Army as it now exists could beat the Russians with the greatest of ease, because, while the Russians have good infantry, they are lacking in artillery, air, tanks, and in the knowledge of the use of the combined arms, whereas we excel in all three of these. If it should be necessary to fight the Russians, the sooner we do it the better.”

It is therefore reasonable to point out these correlations and suggest that at least one reason the United States deployed atomic weaponry was to send a tacit threat to the Soviet Union by using two Japanese cities and their people as guinea pigs (which I must note is something the Japanese were perfectly willing to do to innocent Chinese people with their infamous Unit 731, which killed magnitudes more than the atomic bombs did, but regardless). But as compelling this circumstantial evidence is, it’s still just circumstantial evidence and only demonstrates correlation. It’s also, in my opinion, too cynical to suggest that this was the only reason. I pointed this out during discussion time in my class so many years ago and I’ll repeat it now: the mainstream and revisionist schools can both be true. In fact, the best way to demonstrate that is look at the hypothetical motivations at work when it comes to the second atomic bomb: the “Fat Man” that exploded over Nagasaki.

As the Atomic Heritage Foundation points out in the aforementioned article, “official reports and personal recollections from the Japanese government indicate that Nagasaki had little effect on decision-making,” and that “critics of the bombings have asked why a second bomb was dropped at all, especially after such a short window of time.” The Foundation article correctly points out, “the plan was originally to drop more than two atomic bombs on Japan,” and that “Manhattan Project figures, including J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves, and military planners such as General John E. Hull assumed that at least two bombs would be needed.” However, these were just recommendations from people down the food chain. Ultimately, as is well-known and by his own desk-adornment, the buck stopped with Truman, and we know he had “casually” announced American possession of a superweapon to Stalin only a month before the bombings. Again, we can question how much he knew or how much he intended, but to simply point out that there were recommendations (or assumptions) that two bombs were needed does not necessarily mean that two bombs would have been planned, much less to “simply” end the war quickly as the traditionalists claim, or to “simply” threaten the Soviets as the revisionists do.

The truth is, the bombing of Nagasaki satisfies both schools of thought because it sent the same message to both the Japanese and to the Soviets: that the United States had more than one of these things. It’s probably the most coldly rational conclusion we can draw about the dropping of the bombs and because of that, it’s likely the one we can say is true with the most certainty. There’s always the possibility that a city being incinerated doesn’t demoralize the enemy—it simply emboldens him. And there’s always the possibility that a single bomb being dropped is seen as a once-in-a-lifetime event. As made plain more than once throughout Oppenheimer, there was still some uncertainty that the Trinity Test wouldn’t simply ignite the atmosphere in a chain reaction that would destroy the world (a very real fear). No one really knew if even one bomb was possible and someone as notoriously cynical as Joseph Stalin would likely be inclined to believe we were, in essence, bluffing. Two of these bombs going off would make it less likely that anyone would assume that. This line of thinking is part of what the Atomic Heritage Foundation calls the “consensus school,” one with which I find the most to agree.

…

But what about the other reasons out there? Why else might we have decided to drop barely-tested atomic bombs on two Japanese cities? Putting aside the patent absurdity of the “because racism” or “because America loves genocide” arguments made by modern Know-Nothings, there are indeed a good number of other factors out there, some cynical, some not. However, they tend to be subordinate to these three schools of thought (that is, the traditionalist, revisionist, and consensus schools), and can’t really stand on their own. Nevertheless, they are worth looking at.

The first reason frequently brought up has to do with sunk cost. In other words, we had dumped so much money into the Manhattan Project—$2.2 billion, which in 2023 money is about $37.2 billion—that it would have been insane to not use the weapon. While this has a certain logic to it, it’s also prey to the sunk cost fallacy, a well-studied phenomenon in psychology and behavioral economics. This isn’t to say that there wasn’t a sunk cost fallacy at work when the decision to drop the bombs was made—after all, it did come down to Harry Truman’s decision, and one person on their own is very vulnerable to making poor decisions based on logical fallacies. But the question of whether or not this even counts as a sunk cost fallacy should be raised because, when it comes down to it, the Manhattan Project was not started or funded just to see if the new weapon would work. The United States was at war and had every incentive to get the technological edge on the enemy, and, as Oppenheimer reminds us more than once, we were trying to get this thing made before the Nazis did1. If you’ll pardon a crude way of saying it, the cost had been sunk along with the U.S.S. Arizona; there is no way a super-weapon was going to be produced without it being used as long as there was a war going on.

Speaking of the U.S.S. Arizona, another frequently-cited reason I’ve seen—and in my personal opinion, both in 2005 and in 2023, the dumbest reason apart from the racism/genocide accusation—is that the atomic bombings were revenge for Pearl Harbor. In all honesty, I don’t want to dwell on this “reason” for any longer than I have to because it completely defies logic, reason, and understanding of history. The first thing to point out is that this revenge had already been exacted back in 1942 (and being planned in late December of 1941) in an event known as the Doolittle Raid. This was, according to almost every source imaginable (including General Jimmy Doolittle himself), done to boost the morale of a shaken American people and achieve retribution for the attack on December 7th, 1941. This is not even to mention the heinous firebombing of Tokyo that had occurred earlier in 1945 that one could reasonably argue was even worse than the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in terms of its wanton cruelty in its use of napalm. Revenge for Pearl Harbor had long-since been achieved, both in bombings and in battle (the Battle of Midway comes to mind). Even if one could point to someone in the chain of command making comments about Pearl Harbor, that simply reveals animus; nothing about systemic motive. And the idea that everyone of consequence involved in the Manhattan Project and the U.S. military and the Office of the President were all animated by the same revenge-driven animus reveals a patently absurd assumption about how human beings behave.

The last potential reason worth dwelling on is a political one. By the summer of 1945—really before that, especially in some circles—Americans were exhausted by war; they had endured both personal sacrifices and economic hardships due to the continued war effort. This has been demonstrated in interviews (like in Ken Burns’ excellent The War miniseries) with people who lived through it. And if you think about it, the conditions under which Americans lived—especially after escaping the Great Depression—would be hard on anyone. The war had led to rationing of essential goods, like food, fuel, and clothing, which impacted everyone’s lives. Families also had to cope with the absence of loved ones who were serving overseas, and there was a constant stream of news about casualties and the challenges faced by soldiers on the front lines. It’s admittedly a dramatization (but one based on a true story), but the scene in the masterpiece Saving Private Ryan where the Ryan’s mother is given the news of her sons’ passings was a very real event in many American lives.

By 1945, whatever Americans might have thought about the war’s righteousness or the evil of their enemies, there was a strong desire among Americans to see the war come to an end and for their loved ones to return home; people were eager to move past the wartime hardships and rebuild their lives.

The United States being a democracy, President Roosevelt and President Truman were well-aware of any disquiet that might be occurring about the war’s continuity. There was incentive—a very real political incentive—to end the war as soon as possible. While it’s unlikely that the Japanese would have continued fighting deep into 1946 and 1947, Truman had midterms and a future presidential election to contend with. To ask anyone to be the president that prolongs a war no one wants anymore, especially one on the scale of destruction of the Second World War, is asking for a president to lose any future political contest he or she might enter. I can see this being a potential reason for Truman to make his final decision on dropping the bombs, but by no means does this serve as a singular explanation. It’s one thing to be glibly cynical about American politics—believe me, I know—but it’s another to assume that that’s all that motivated the men and women in charge of bringing the Second World War to its conclusion.

…

This remains a constant debate in World War II circles; I’ve read through numerous Reddit threads, read a number of articles, glanced through books, and even asked ChatGPT for some summaries and it’s clear that not only is there no real consensus on the question of why we dropped the atomic bombs on Japan, but that there likely never will be. The closest we can come to is to admit that there were probably multiple reasons for the United States doing what we did. This doesn’t devalue the question itself; in fact, it’s a lively debate and one always worth having if only because it can help us think about why people make the decisions that they do, especially those with incredible consequences. And it’s those incredible consequences that really matter, especially for this debate.

The truth is, the reasons for why the United States deployed atomic weapons against Japan don’t really matter as much as a much more crucial question: would deploying atomic weapons ever be the right thing to do? That’s really the question people are answering when they subscribe to the traditionalist school (yes), the revisionist school (no), or the consensus school (it depends). As much sympathy as I have for the consensus school (which inherently suggests a sympathy for both the traditionalist and revisionist schools and what answer to this question their preoccupations imply), I don’t even know if I’m willing to say “it depends.” On what? On the one hand, how the atomic bombs were used, frankly, is probably better than how they might otherwise have been used (say, if the Nazis had developed them first, or had the Soviets developed them first without knowledge of what they did to a human population or knowledge that we also had the ability to obliterate them). On the other, the images that emerged from Hiroshima and Nagasaki—not to mention the harrowing accounts—are the stuff of nightmares. As evil and horrific as the Japanese crimes against humanity were—and they were—did the people turned into dust shadows deserve their fate? Did they deserve the weeks, months, or years of radioactive torture? Who would I be to make that judgment? Would anyone?

This is not even to speak of the greater implications of atomic weaponry. Are we truly living in a better world where it’s clear that with the approval of a small number of people and the proverbial press of a button hundreds of millions of people could be destroyed in mere minutes? On the one hand, I find the idea of deterrence compelling—why would anyone want to make the decision that leads to that eventuality, that is hundreds of millions of dead people? Why would I send world-destroying weapons against my enemy if they’re just going to do it to me, leaving only ruins and death for the survivors to squabble over? The great powers of the 20th century—the United States and the Soviet Union—came very close to nuclear war more than once; and yet, we never actually did. Russia, still awash in more than enough nuclear weapons to end life as we know it, is fighting an old-school land war in Ukraine; and yet, we still have yet to see any deployment from them or us (fingers crossed). There are plenty of nuclear-powered hotspots all over the world—North Korea, India and Pakistan, Iran and Israel—and yet, nothing has happened, at least not yet. Is this because we all collectively understand what it might mean if we set these weapons off? And while I certainly hope so, that’s hardly a source of comfort. How can it be? The power to destroy ourselves is there; it’s been there for almost 80 years and there is no sign it’s ever going to go away. As much as anyone, especially including me, can appreciate being in control of our own destiny as a species, this is probably the most terrifying trade-off one can imagine.

These were the things—and likely far more—that plagued Oppenheimer, something the film takes great pains to depict (and with shocking poignancy). As he ruminates at the end of the film in a conversation with Albert Einstein, they had, in essence, destroyed the world by making such an impossible task finally possible. Empires rise and fall and many of them are led by men and women who believed that the world’s fate turned on their decisions, but their world was so much smaller back then; their weapons so relatively puny. But all that changed in 1945. Mankind can be brought to heel by pandemics and natural disasters—and odds are that will be what does us in. But what was unleashed by J. Robert Oppenheimer and his comrades (not to mention their German and later Russian counterparts) did something unthinkable: it placed that power, formerly only in the hands of unfeeling, unthinking, uncaring microorganisms, asteroids, and geological forces, in the hands of deeply-feeling, deeply-thinking, deeply-caring—that is, deeply flawed—human beings.

While I am sure there are revisionist types out there who want to jump through hoops and try to explain how “ACKTHyually” the Nazis would have only used it on the evil Soviets, this borders on tiresomely contrarian at best and naïvely good-faith in their interpretations of Adolf Hitler at worst.