Israel, Gaza, and Three Root Causes: A Primer

An attempt at boiling down what created this conflict

Like many of you reading this, I’ve been remaining pretty glued to the ongoing events in Israel and Gaza after Hamas’ barbaric attack on October 7th, 2023. I’m also relieved to know that the few Israeli friends I have are safe, and beyond sad about the mounting casualties in Gaza. However, no amount of horrifying and heart-wrenching footage of what many Palestinians are going through right now is going to change the fact that those supposedly fighting and clamoring in their name are barely even trying to hide the fact that they sound little better than the Nazis or, to make a more pointed comparison, the Ustashe of the Independent State of Croatia (who, let’s remember, had no compunction about doing very similar things to Jews, Serbs, and Roma that Hamas did to their Israeli victims). In fact, as one of my Israeli friends and listeners said to me in an email, “my news feed has been flooded with stories that sound like quotations from your episode about the Ustashe. It is unbelievable, and I think the Ustashe is a good historical reference.”

The reason this comparison is so relevant is because, as my friend also stated, “the attack itself was characterized like an attack of an angry mob, with all the barbaric cruelty of such a mob,” but “that isn't the case and that is what is the most horrifying thing about it.” The objective, my friend wrote, “was to murder civilians,” with “the saddest thing” being “that most of these settlements [that were attacked] were of pro-Palestinian Israelis.” But this only begins to illustrate the tragedy of what kicked all of this off. My friend wrote that “One old lady kidnapped to Gaza used to go to the cross road every Friday holding a sign: ‘Stop the occupation,’” while “the elected governor of the area was killed while he left his house with a pistol in an effort to save his children, gave, just a month ago, an interview in which he begged the government to ease the pressure on his neighbors in Gaza.” This demonstrates that, like with the Ustashe, the barbarism was the point, regardless of any speculation I might have about long-term goals. No matter the goals, the barbarism was the point. That, despite what so many truly awful human beings in my own country might suggest, is not the actions of a freedom fighter: that is what hate-motivated religious ethnofascists do. Indeed, as my friend concluded, “the guys that planned the attack on Saturday are the first Muslims in history that truly are ‘Muslim Nazis.’”

Not to spoil too much about the ongoing History Impossible series of same name, I’ll say that I both agree with my friend and disagree, if only in specifics and because of typical pedantry on my part. There certainly were “Muslim Nazis” before 2023, but there was really only one man who, in my opinion, could be called such without any sort of equivocation. Regardless, my friend’s overall point is very well-taken: the savagery on display, which will no doubt produce far, far more savagery in the months, if not years to come hasn’t been seen on this scale for a very, very long time and resembles nothing less than genocidal rage (that may well be reciprocated in kind). Often, many people will say things like “this is like Israel and Palestine” to describe cultural divides that exist in our country; in all honesty, it’s likely better at this point to use the old fractured Kingdom of Yugoslavia as our guide for how this shakes out between all of the cultures involved. I think people calling what happened part of a cycle are missing the point: it wasn’t really a cycle anymore. But it probably will become one now, especially depending on how the IDF conducts itself in the coming weeks. What this means, if the worst is to come to pass, is that the world must brace itself for the reciprocal violence of Yugoslavia being carried out on a global scale.

However, now that some time has passed, there are those out there—much to the understandable chagrin of many Jews—who are beginning to talk about “root causes.” This is already a loaded term because if the historian—amateur, in-training, or otherwise—is not careful, they will fall into the trap that basically reduces everything to “well, at the beginning of time…” (or perhaps less absurdly but no less reductively, “when these people started worshiping different gods…”). However, believe it or not, pinpointing at least some of the root causes of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict isn’t that difficult. This is even more true if you grant the reality that, yes, the Jews were there first and got largely run out of the region over two millennia ago, and that, yes, Islamic culture became the dominant one over one millennium ago, and that all this only changed about 80 years ago. Those are all facts, and arguing over “who was there first” is simply unhelpful and rooted in theological essentialism. Once you do that, you can start to trace where a lot of this came from.

However, this still has its own difficulties, which are completely normal in producing history: what to include and what to leave out. You can take an all-encompassing approach, and that’s probably the best way to do things with something so complex—I recommended it in my last essay, but I’ll recommend it again, that if you want a detailed breakdown of these origins, you can do little better than MartyrMade’s Fear and Loathing in the New Jerusalem series (or obviously the aforementioned Muslim Nazis series on History Impossible).

The problem is that a lot of folks don’t have 20-40 hours to spend on this question of root causes of the Israeli-Gaza War of 2023 when they want answers now. This isn’t a dig, just an accurate representation of life—we’re all very busy and only have so much head space and time to cram only so much information. Because of this, I thought I might try and add a little clarity to what those root causes—the true starting points that put Israelis and Palestinians on this collision course—actually were. And, based on my own research, I came to the conclusion that there were three inescapable root causes that, while not pleasing everyone, will displease the least amount of reasonable people thanks to the inescapable fact that these three root causes were indeed significant.

The first and possibly most important thing to point out before we get into these causes is that they are by no means definitive. There are plenty of things that have happened in the last 50-60 years, for example, that probably warrant inclusion. But I am woefully uneducated about such events—from the Six Day War and the Yom Kippur War, to the events in 2006 and 2014—and I don’t want to lengthily comment on things of which I don’t feel like I have a full grasp. In addition, I don’t think it is accurate to call events that are that recent—relatively speaking of course—the “roots” of what has been and what will continue to happen. They serve as branches, no doubt important and load-bearing branches, to what is happening now. However, to fully grasp how we got to where we have gotten, I think we need to go back 120 years.

And please keep in mind that even though I am willing to defend these three factors as what I see as the root causes of the current conflagration, these really are just my opinion. Many other valid factors can (and should!) be added to this, so please add your own “top three” in the comments (or via email if you don’t feel like being public about it; historyimpossible at gmail).

But as far as I am concerned, these are the three vital root causes that helped start this region of the world down the vicious and violent path it is currently on.

…

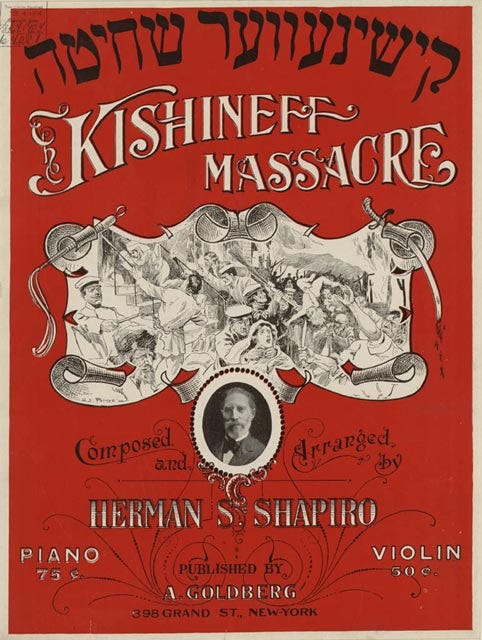

1. The Kishinev Pogrom

Russia, perhaps even more than Germany, has one of the most checkered relationships with the Jews living within its shifting borders over the centuries. Like in many parts of Europe, the Jews of Russia were isolated from the rest of the population for centuries, confined mostly to their shtetls where they mostly kept to themselves. This began to change in the 19th century as Jews began to assimilate more into Russian society, taking up customs and language along the way (again, like in many parts of Europe; particularly Germany). However, with this gradual assimilation came greater repression from the Russian government, thanks largely to the influence of Tsars with few nice things to say about Jews. Alexander II was less of a reactionary bigot than his son Alexander III, but even with his famous abolition of serfdom across the Russian Empire, he still forbade Jews from hiring Christians for servant work and largely restricted travel for them, as well as land ownership. This was pretty typical as far as repressive European policies against Jews went.

However, in 1881, Alexander II was assassinated in a bombing—probably one of the first recognizably modern acts of terrorism in Western history—by the Russian terrorist organization Pervomartovtsy, a group of early anarcho-socialist revolutionaries. Despite most of the assassins being caught and executed, bloodlust was in the air, and Jews, as they often have in times of strife like this, became the scapegoat. What followed was a massive wave of pogroms across what is now Ukraine, in which thousands of Jewish homes were demolished and hundreds of Jews of all age and sex were injured (with some being killed). This unfortunately set the tone for what was to come a few decades later.

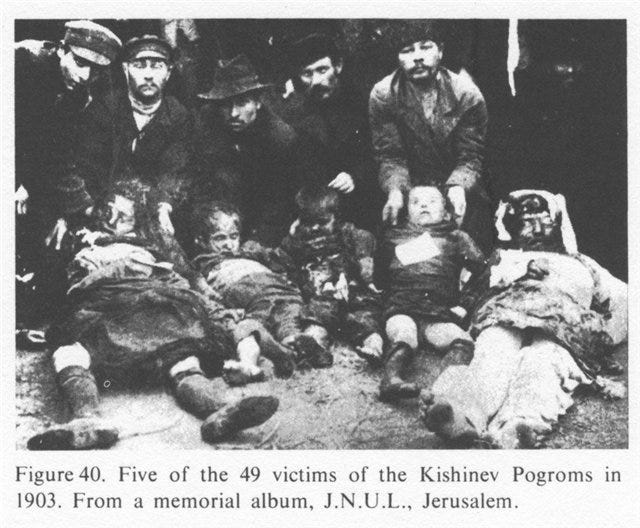

On Easter of 1903, in what is now modern-day Moldova, the capital of the Bessarabian Governate known as Kishinev had a dark cloud hanging over it. Preparations had been made; Christians were encouraged to paint or otherwise mark their front doors with crosses to distinguish themselves from the intended targets that day. The local police were primed to collude or turn a blind eye to what was about to happen. Historian Edvard Radzinsky has even suggested that, based on the memoirs of Sergei Witte, Russia’s first Prime Minister elected in 1905, that he discovered that proclamations had been created and distributed by police forces. This included several anti-Jewish articles in the local paper, essentially preaching the necessity of violence against them. In essence, the population was being given the green light to do what they wanted, directly from the pens of their authorities. This wasn't the first time this had happened, but as writer and scholar Edwin Black puts it, “Soon the world would see nothing less than another state-sponsored Russian pogrom. But this one would be far more ghastly than any that had preceded it.” The New York Times, in its April 28th, 1903 issue, summarized as much:

The anti-Jewish riots in Kishinev, Bessarabia, are worse than the censor will permit to publish. There was a well laid-out plan for the general massacre of Jews on the day following the Orthodox Easter. The mob was led by priests, and the general cry, ‘Kill the Jews,’ was taken up all over the city. The Jews were taken wholly unaware and were slaughtered like sheep. […] The scenes of horror attending this massacre are beyond description. Babies were literally torn to pieces by the frenzied and bloodthirsty mob. The local police made no attempt to check the reign of terror. At sunset the streets were piled with corpses and wounded. Those who could make their escape fled in terror, and the city is now practically deserted of Jews.

The pogrom began with local Eastern Orthodox seminary students joining several gangs of drunken Albanian and Moldovian students roaming the streets who were shouting abuse and hassling local Jews. Things took all of five proverbial seconds to escalate since the Eastern Orthodox seminarians were armed with iron bars and axes and a sense of righteousness and bloodlust in their minds. What started as an escalation to property destruction and theft akin to the George Floyd riots of 2020 quickly turned into brutal, unceasing assault and outright murder akin to what happened near Gaza in 2023. Women were gang-raped in front of their parents, children, and husbands, while being mocked by onlookers for being Jewish whores. There are several accounts of mutilations, including Jews getting nails driven through their nostrils and even disembowelment followed by feathers being stuffed into the victims' wounds. Edwin Black elaborates based on the contents of a letter sent to the New York Times explaining the extent of the slaughter:

“Hundreds of Jews were viciously set upon, many being brutally murdered and dismembered where they stood. A two-year-old Jewish boy was seized by the mob and his tongue cut out as a trophy before they killed him. The meek grocer Weismann, already blind in one eye, pleaded for mercy and offered the crowd his last sixty rubles. His money was accepted, and then his grocery was destroyed nonetheless—but not before his other eye was gouged from its socket by a hooligan who screamed, 'You will never again look upon a Christian child!'”

This all went on for two full days. And the message was the pure nihilism of any anti-Jewish pogrom: you are all pests and we don't want you here.

The pogrom quickly made global news at a time when global news was far, far slower than it is today. President Theodore Roosevelt’s Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine even mentioned it by name, despite it being largely inspired by the Venezuelan crisis of 1902-1903. This, of course, necessitated a response from the Tsarist government, with Russian ambassador to the United States Count Arthur Cassini claiming the following:

The situation in Russia, so far as the Jews are concerned is just this: It is the peasant against the money lender, and not the Russians against the Jews. There is no feeling against the Jew in Russia because of religion. It is as I have said—the Jew ruins the peasants, with the result that conflicts occur when the latter have lost all their worldly possessions and have nothing to live upon. There are many good Jews in Russia, and they are respected. Jewish genius is appreciated in Russia, and the Jewish artist honored. Jews also appear in the financial world in Russia.

In other words, yes, Jews were indeed the victims of barbarism in our country, but look at how they live, look at their influence! Certainly, Cassini implied, they had it coming. But of course we condemn such action. But they had it coming. (Does this sound familiar?).

Other pogroms followed Kishinev, including another in that town only two years later that left 19 more Jews dead. The worst was the Odessa riots of 1905 in which hundreds of Jews were killed, and was part of a massive wave of pogroms that occurred after Tsar Nicholas II issued his infamous October Manifesto, titled “The Manifesto on the Improvement of the State Order.” Many of these pogroms, including the second Kishinev pogrom, occurred as a natural outgrowth of protests against this manifesto. As historian Robert Weinberg explains in his contribution to the collection Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History, “In the weeks following the granting of fundamental civil rights and political liberties [by the Tsar in his manifesto], pogroms directed mainly at Jews but also affecting students, intellectuals, and other national minorities, broke out in hundreds of cities, towns, and villages, resulting in deaths and injuries to thousands of people.”

The root causes of this root cause are complex enough on their own and require full chapters and even entire books to untangle, so I will leave it to the real historians like Weinberg to do that (his chapter does an admirable job doing so). The point is that thanks to the pogroms in Russia that began as a trickle and then resulted in a tsunami, Jews in the old Russian empire—two million in the 40 years between 1880 and 1920, mind you—had it made clear to them that they could no longer stay. And the amount of places where they could go, which initially included the United States and the United Kingdom, quickly began to shrink. In 1905, the United Kingdom passed the Aliens Act in a direct effort to stem the tide of Jewish immigrants into their country, and later (but no less significantly), the United States passed the Immigration Act of 1924, which set quotas on the number of Eastern European immigrants (which included Jews) who could enter the country (while outright banning immigrants from Asia altogether, serving as a nice “yes and” to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882). However, there was still one option for a lot of these mostly Russian (but increasingly more Eastern European) Jews trying to escape the constant threat of slaughter: Palestine.

The Modern Zionist movement, only six years old at the time of the Kishinev pogrom, had been building a slow-but-steady momentum during those six years under the influence of the Austro-Hungarian Jewish activist and journalist Theodore Herzl. However, once Kishinev occurred and the world’s collective outrage came to bear, Herzl and other Zionists—particularly hardliner Revisionist Zionists like Ze’ev Jabotinsky—wasted no time in using the massacre as a rallying cry to what they saw as the moral imperative of a Jewish state. This moral imperative only became easier to make as the massacres of Jews increased in 1905, but it was the first pogrom in Kishinev that served as the symbol for the nascent Zionist movement. The rallying cry heard at demonstrations and printed in propaganda was “No more Kishenevs!”

One could argue that this was just a cynical way for Herzl and other imperialistic Jewish aristocrats to never let a good tragedy go to waste. However, if one feels that way, one must ask themselves: what should anyone expect, given what had happened by 1905? This push for mass Jewish immigration to Palestine might have been a form of imperialism, but it had less to do with the exploitative extraction of resources for some far-away mother country. It had more to do, in Herzl’s and many Jews’ eyes, with the obvious fact that many Jews would never be safe anywhere except in their own country. Which, in 1905, they did not have. Regardless of Herzl and other Zionists' imperialist tendencies that definitely did exist—there is no way to deny that and we’ll return to that in a bit—the Jews of the Russian Empire didn't have the luxury of idealistically yearning for a long-forgotten, fabled homeland. They were being given two choices: take your chances and leave or stay and probably die a horrible death at the hands of a mob.

It’s crucial to understand the Palestinians weren’t even really being consulted about this, making it all the less likely that they’d hear about the plight of these Jews fleeing persecution and murder and feel some sympathy. There were certainly negotiations occurring between the Zionists and the Palestinian leadership (such as it was), but it became clear, especially by the 1910s and 1920s, that the Jews were coming whether the Palestinians liked it or not. This puts a political stink on the mass migration that was occurring, especially if you have an allergy to imperialism as I do, but given what the survivors of Kishinev and Odessa and all the other pogroms that had occurred at the beginning of the 20th century saw and experienced and lost, I find it hard to believe that anyone who considers themselves a good progressive or even a good liberal—the kind of person appalled by the treatment of refugees on our own southern border—would be able to hand-wave away such experiences of all the men, women, and children escaping the horrors of late Tsarist Russia.

…

2. The Balfour Declaration

The next symbolic but no less important moment in the history of Zionism and the formation of the Jewish state occurred in the midst of the First World War, while much of this early mass immigration to Palestine was occurring. This first point is important because as cataclysmic as the Great War was, it wasn’t as if everything else just stopped on a dime. Palestine was hardly an important location at the start of the war—it was truly seen as the backwater of the Ottoman Empire, which was already teetering on its last legs as the war began. Little did many in the British Empire know that when they obtained Palestine as part of the peace settlement with the defeated Ottomans in 1918 that this strip of coastline would become the largest political flashpoint in the region for the next century.

However, this is not to say that the British didn’t believe this strip of land was significant. This was thanks to some within the British government who were fully aware of Palestine’s significance to many Jews out there, including the fabulously wealthy and influential leader in the British Jewish community, Lord Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild. Rothschild—who was indeed one of those Rothschilds so favored by anti-Semitic conspiracy theorists to this very day—was, like an increasing number of Jews across the world, a staunch Zionist, thanks largely to his friendship with the immensely significant Zionist and Jewish figure Chaim Weizmann, who was president of the World Zionist Organization that had formed under the direction of Theodore Herzl (and who would eventually serve as Israel’s first president in 1949).

Thanks to this relationship (and many others), Weizmann maintained a high level of influence within the British government and was able to act as a sort of super-lobbyist for the formation of a Jewish state. It should be noted that he was so dedicated to the idea of securing his organization’s goals that while he certainly wanted to get support from the United Kingdom and any other powerful nation that might listen to him, he was more than willing to make Israel happen without their help. At the First Zionist Congress, Weizmann stated the following:

A state cannot be created by decree, but by the forces of a people and in the course of generations. Even if all the governments of the world gave us a country, it would only be a gift of words. But if the Jewish people will go build Palestine, the Jewish State will become a reality—a fact.

But the formation of this new Jewish state was by no means inevitable, even with a will like Weizmann’s. Plus, he had his friend Baron Rothschild and many others (including by then future Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who had opposed the Aliens Act of 1905 and supported Jewish statehood since 1908) in his corner, so he was going to use the opportunities that presented themselves to him to the best of his ability. In Weizmann and many other Western Zionists’ minds, nothing could stop them from achieving their goals if they could bring the might of the British Empire to bear. And this was a common view among British Zionists. Another famous Zionist named Herbert Samuel wrote, from his position as postmaster general, a memorandum in 1915 advocating for a British imperial conquest of Palestine, a mere three months after the Ottoman Empire entered the Great War. Samuel was, as historian Tom Segev puts it, “characteristically cautious,” and made it clear in the memorandum “the time is not yet ripe.” However, he was saying the quiet part out loud: Zionism was the goal, imperialism was the tool.

Quick as we are (and again, in my opinion, should be) to denounce imperialist tendencies, it’s important to remember that this was the cultural standard of the time, especially within the British Empire. The idea that one power could conquer a territory, especially one of a nation with whom you were at war, was the right of any nation, and since the British still largely ruled the waves (and weren’t doing too badly during the First World War on the ground by this point), and still held onto colonies around the entire globe, so they had a pretty high opinion of themselves. This was thus how the British (and the Zionists among them) approached the subject of what to do with the Ottoman territories once the First World War ended. As historian Tom Segev writes in One Palestine, Complete:

The proposal to seize Palestine accorded with the way people in London were thinking at the time. When they spoke about the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, there was a tendency to think of it as a large cake: this country would get one slice, that country another; the territory the Ottomans were about to lose was considered booty to be shared out among the victors. “We have arrived at a supreme moment in the world’s history. The map of the world is to be remade,” wrote one of the Zionist periodicals in England. There were also thoughts about an exchange of territory; of France conceded on Palestine, as one proposal suggested, it would receive some colony in Africa in exchange.

The memorandum by Herbert Samuel, cautious as it was, went even further in its imperialistic rhetoric than the Zionist publication quoted a moment ago. In it, he claimed, perhaps to appeal to more British imperial sensibilities or perhaps revealing his own attitude, that this, as Tom Segev puts it, “would allow Britain once again to fulfill its historic calling of bringing civilization to primitive lands.”

This is why the characterization of Zionism, at least in the context of its connection to the British Empire, as being one of imperialism isn’t completely unfair. In fact, there’s really no other way to describe it, both by modern standards and by historical ones. But thanks to the conditions set by the pogroms in Russia (and especially the conditions that were to come in Europe), it’s a much more morally complex form of imperialism than I think those who want to condemn Zionism wholesale are capable of appreciating. But with that said, imperialism is imperialism, and as a mindset, it existed in spades at the close of World War I. This is where Arthur James Balfour enters the picture.

Balfour was the Liberal Party’s Prime Minister in 1903, and afterward, had developed a relationship with Britain’s Zionists—namely with Chaim Weizmann. This relationship would prove fruitful for the Zionist movement since, after a lengthy dinner and conversation that went well into the wee hours of the morning one night in 1916, Balfour forcefully declared himself to be a Zionist during a cabinet meeting in which he served as Foreign Secretary to Prime Minister Lloyd George’s government. This set events in motion that would lead to his eponymous declaration the following year. Before that could happen, Weizmann would continue to develop his relationship with the British government in order to build his influence—even gaining the ear of the Prime Minister Lloyd George—and thus make his and his organization’s dream of a new homeland a reality.

What makes this relationship between Weizmann—and by extension the entire Zionist movement—and the British government extremely problematic is that it helped feed into the conspiracy theories that had long existed (since the era of the Court Jews, really) of outsized Jewish influence in the affairs of gentile governments. What made it even worse was that Chaim Weizmann, his eye squarely on the ball that was Palestinian settlement, actually leaned into these conspiracy theories. As Tom Segev writes, “Weizmann had reason to conjure up the myth of Jewish power and influence, and he rose to the occasion admirably.” He utilized this image (projected through “a fine rage” as an observer once called it) in order to strong-arm British and French representatives Mark Sykes and Georges Picot away from their agreement that proposed a joint Anglo-French occupation of Palestine after the Great War was over. As Segev notes, “Weizmann’s influence could only reinforce Sykes’ predilection for seeing the Jews everywhere and behind every decisive event.” This didn’t make him many friends, even within his own organization, with “some of his colleagues in the movement accus[ing] him of working like a dictator,” as Segev puts it. But in the end, this didn’t stop events from ultimately working out in Weizmann and the World Zionist Organization’s favor.

On November 9th, 1917, two days after it was written, the British press released what would become known as the Balfour Declaration. It was written in the name of Arthur Balfour, who had been working closely with Chaim Weizmann and his friend, Lord Walter Rothschild, on drafting this document. The letter was addressed to Lord Rothschild and read as follows:

Dear Lord Rothschild,

I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty's Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet.

"His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country."

I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.

Yours sincerely,

Arthur James Balfour

The letter wasn’t everything the Zionists wanted—as Tom Segev notes, it “stopped short of designating Palestine a Jewish state” and that the final wording, which Weizmann and Rothschild had no say in producing, “reflected all-around caution.” There was also much work to be done; namely, the Great War still had to be won (and it’s important to note that this was by no means guaranteed, at least in the West; as pointed out in an earlier episode of History Impossible, the German Spring Offensive had a high likelihood of succeeding, if not for the intervention of a little something known as the Spanish flu hitting the German forces harder than the Allied ones). The Declaration also didn’t engender universal sympathy, even within the wider Jewish community. In paraphrasing the famous journalist and author Arthur Koestler, Tom Segev writes, “Here was one nation promising another nation the land of a third nation, wrote Arthur Koestler, who, dismissing the declaration as an impossible nation, an unnatural graft, called it a ‘white Negro.’” But it was a vital pledge, and biggest victory the Zionists had obtained thus far. And it would eventually see the support of the Allied governments and soon, Balfour’s words would indeed become a reality for thousands more Jews headed in the direction of Palestine.

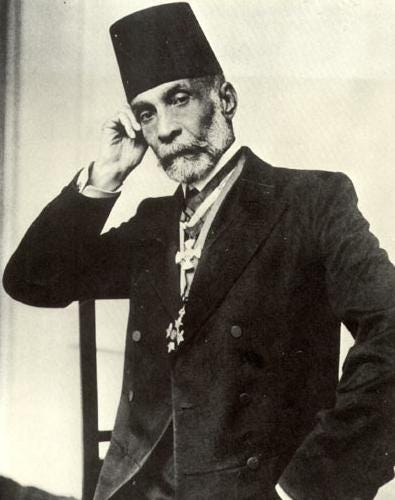

As many of you reading may be wondering at this point, “where were the Palestinian Arabs in all of this?” That’s a good question. They were nowhere to be seen because, as Herbert Samuel implied, they were simply inhabitants of “primitive lands,” subjects to the Sick Man of Europe that was the Ottoman Empire. Surely, they couldn’t possibly understand the gravity of what was at stake, and even if they could, they had no recourse in the matter. They were pawns to be moved in the new Great Game that was the Middle East and if they didn’t like what was about to happen to them in the years that followed the end of the Great War, then too bad. In other words, they weren’t there because they weren’t consulted, not in any meaningful sense. And to say that the reaction of Palestinians was one of pure outrage is putting it mildly. Ninety percent of Palestine was made up of Muslims and Christians, and they uniformly opposed the Balfour Declaration. A prominent figure in Palestinian politics (and a member of a certain prominent Palestinian family) and Mayor of Jerusalem named Musa Kazim al-Husseini would issue a petition in the name of his Muslim-Christian Association on November 3rd, 1918 that read in part as follows:

We have noticed yesterday a large crowd of Jews carrying banners and over-running the streets, shouting words which hurt the feeling and wound the soul. They pretend with open voice that Palestine, which is the Holy Land of our fathers and the graveyard of our ancestors, which has been inhabited by the Arabs for long ages, who loved it and died in defending it, is now a national home for them […] We Arabs, Muslim and Christian, have always sympathized profoundly with the persecuted Jews and their misfortunes in other countries [...] but there is wide difference between such sympathy and the acceptance of such a nation [...] ruling over us and disposing of our affairs.

One can easily sympathize with Musa al-Husseini’s words here, and certainly his sense of outrage, especially since he, at the very least, paid the necessary lip service to the plight facing the Jews around the world. But the choice of allowing this influx of people into his nation—which had just been freed from Ottoman domination only to be replaced with that of the British—had been taken away from him and the rest of his people. As far as the British and the Zionists like Chaim Weizmann and Herbert Samuel were concerned, it was never his choice to make. And arguably, that attitude, so perfectly articulated in Arthur Balfour’s promise to the Zionist movement, is significant for setting the tone for what was to come and perfectly incentivized the responses by later Palestinian nationalists to be much more zero-sum and violent in nature.

…

3. The Grand Mufti

“For us Muslims, it is unworthy to utter the word Islam in the same breath with Judaism since Islam stands high over its perfidious adversary.”

—Hajj Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

I have likely already said most of what needs to be said about this man’s life during this era of Palestinian history in the long-running “Muslim Nazis” series. I obviously encourage you to listen to the first five episodes of that series to get the fullest picture as possible of the man, his life, and what drove him to do and say what he did and said, but I’m going to do my best here to remain as concise as possible in exploring his role as a root cause—probably my “favorite” root cause—in setting Israel and Palestine on the course they have found themselves.

It’s easy to overlook Amin al-Husseini as a figure of influence because of his ultimate disgrace—both in becoming an exiled lickspittle (and minor facilitator) of the Nazis during the Second World War and his perceived failure to stop what the Arabs would call the Nakba (which is derived from the same word “shoah,” hence al-Husseini’s later use of the word “Holocaust” to describe what happened to the Palestinians) in 1948. It’s even easier to downplay his influence, thanks to the waters being muddied by figures like Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu claiming as he did in 2015 that Amin al-Husseini was the man who incited Hitler to kill the Jews (despite the fact Jews were already being slaughtered in the east and the minutes of that meeting are widely available). However much of a failure al-Husseini might have indeed become and be seen as, and however much his legacy has been saddled with fake history, his importance in shaping and facilitating events in very particular directions during the key early years of mass Jewish immigration into Palestine should not be understated. As Herbert Samuel’s biographer Bernard Wasserstein put it when describing Samuel’s decision—because Samuel had become British High Commissioner in Palestine—to appoint Amin al-Husseini as the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem in 1921, it was “a profound error of personal and political judgment.”

While Tom Segev, resisting hindsight bias like any good historian does, explains that in the context of the time and place, the appointment of al-Husseini to that position was “perfectly reasonable,” it’s impossible to look at it this way with hindsight, especially when trying to pinpoint a significant root cause of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Amin al-Husseini had indeed started out as an idealist (he was strongly influenced by earlier Arab nationalists like Muhammad Rashid Rida, and ran a nationalist club during his time in college), he had a darker, more ambitious streak within him. As I’ve frequently invoked in the “Muslim Nazis” series, he was the Peter Baelish, or Littlefinger, of Palestine. What al-Husseini valued above all else was power and influence. This explains why he didn’t just stop at becoming the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem—that is, the religious leader in charge of Jerusalem’s holy places like Al-Aqsa mosque—and he maneuvered his way into becoming the President of the Supreme Muslim Council, which acted as the authority over all the Muslim waqfs and sharia courts in Palestine. This way, he held both a monopoly on religious and political (as well as financial) power in Palestine, however limited it was by the British Mandate and Zionist influence. While one could read this as a way to maximize efficacy in resisting the encroaching forces of British and Zionist oppression, this simply doesn’t track with how al-Husseini operated. His political rivals were frequently cowed by threats, intimidation, and, it’s been suggested in some sources, murder. His ruthlessness at securing power by any means necessary was never in doubt. But there was something even darker at work within him, that likely already had started to lurk under the surface when he secured his position as Grand Mufti.

When more sympathetic scholars discuss Amin al-Husseini’s hatred of Jews, it’s usually in the context of his development as a nationalist leader and in his frequent efforts to fight against Zionism becoming stymied, this doesn’t track with the reality that al-Husseini’s more anti-Jewish impulses had started to show themselves within only a few years of his taking the post. We know for a fact that in 1928, he proclaimed that “The Arabs have learned by bitter experience the unlimited greedy aspirations of the Jews.” And as circumstantial as this evidence is, we know, thanks to the recollections of Winston Churchill, that the English translation of the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion forgery had made its way into Palestine by 1919. And, according to Churchill, the following statement was made to him in 1921:

The Jews have been amongst the most active advocates of destruction in many lands. It is well known that the disintegration of Russia was wholly or in great part brought about by the Jews, and a large proportion of the defeat of Germany and Austria must also be put at their door.

The man who said that was Musa Kazim al-Husseini, the mayor of Jerusalem from whom we heard being so reasonable about British and Zionist imperial encroachment earlier in our story. And considering the way his appeals had been treated by the Zionist-influenced British government, it’s hardly surprising that his thoughts could curdle this way. And, as you can no doubt tell from the similarities in their names, he was a blood relation to the soon-to-be-at-the-time Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini. Again, this is all circumstantial, but as I stated in an earlier episode of History Impossible, I find it very unlikely, especially given his later apparent references to it, that by 1928 that Amin al-Husseini hadn't read or at least been made aware of the contents of the Protocols, considering how closely he and Musa worked together over the years.

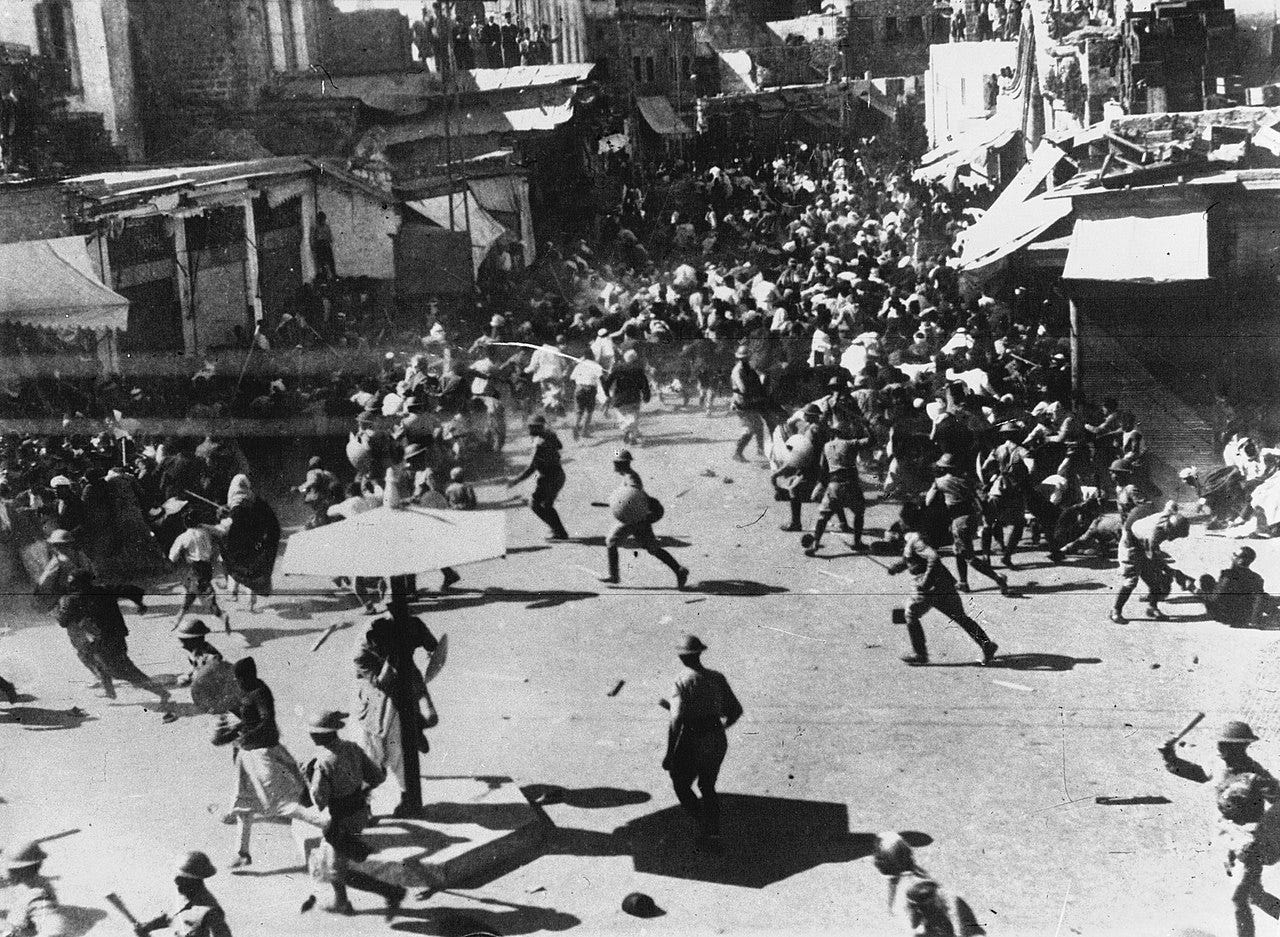

Amin al-Husseini’s activities in the 1920s are good fodder for either side of the debate on whether or not he can be held responsible for the riots that flared up at various points, particularly in the extraordinarily violent outburst of 1929. There is reason to believe that, however much responsibility he may have had for things getting so out of hand on more than one occasion, that he hadn’t intended for full-fledged pogroms to break out across the Palestinian territory, and this was largely thanks to his politically tactical nature and his awareness that the British authorities could just as easily remove the power they had allowed (and enabled) him to obtain, if they came to see him as responsible. The incentives just weren’t there, Jew-hatred or no Jew-hatred in his heart.

However, eventually they did hold him responsible for the chaos that was building in the streets of Palestinian cities—particularly Jerusalem—thanks to the agitation he was no doubt sowing. This was despite two very important facts, including that 1.) the Zionists—particularly the Revisionists under Ze’ev Jabotinsky—were consistently out for Arab blood and welcomed any chance to engage in both reprisal and preemptive terrorism, and 2.) there were other, far more radical Palestinian nationalist groups in town (like al-Istiqlal and al-Qassam), as well as another powerful Palestinian family—that is, the Nashashibis—who had a long-standing rivalry with the Husseini family. These facts are often utilized by both scholars and observers who want to be conservative about (if not outright downplay) al-Husseini’s influence on the events that occurred across the Arab world in relation to Palestine, but in my view, this misses the point. Even if Amin al-Husseini didn’t enjoy universal, uncontested influence, he still enjoyed a lot of cultural influence and, if you’ll recall, political power. He often made speeches to crowds and there was even an instance early on where a crowd joyously roared, “The sword of religion, Hajj Amin!” His influence over both radicals and regular people began to dwindle as it became clear that he was trying to play both sides, but his religious, political, and financial influence was always there to cushion his fall.

It was in the latter half of the 1930s that Amin al-Husseini was forced into making a choice—continue to play nice with the British authorities or to finally take up rhetorical arms against them in what history has come to call the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939. The consequences for this choice are far too numerous for us to fully cover here, but the main one for our purposes begins with his turning on the British. This is not to suggest that he was unreasonable for doing so; by October of 1936, there were over 1,000 dead Palestinians thanks to the ongoing Arab Revolt and al-Husseini, as observed by the then-British High Commissioner Wauchope, was mainly afraid “to be left alone in the open, liable to be accused by friend and foe of treachery to the Arab cause.” This wasn’t just self-interest (though that certainly weighed heavily with al-Husseini, as it does with us all), but rather, it was a moral calculus that even someone as power-hungry as him could rationalize away. However, soon after he essentially declared war on the British, letting the diplomatic mask drop, he let another mask drop. In October of 1937, in the midst of propagandizing for the cause, he made a speech titled “Appeal to All Muslims of the World,” which would follow him for the rest of his life, and for good reason. There is, in truth, no explaining the speech away, and thankfully at this point, very few but the most ardent transferred nationalists to the Palestinian cause would try. In the speech, al-Husseini would proclaim the following:

Since the earliest days of their history, the Jews have been an oppressed people...and there must be good reason for that. This new generation [of Jews] spread out across Mecca, Medina, Syria and Iraq—the lands where milk and honey flowed. But this generation was still worse than the previous one, as says the Arabic proverb: “A dog had a young one, but the young one was more like a dog than the one that created it.” […] The Romans very quickly recognized the danger posed to the land by Jewry and therefore decreed sharp measures against the Jews. Added to this was the fact that a serious epidemic—the plague—broke out, which in general opinion had been brought in by the Jews. When the doctors, too, declared that the Jews were the epicenter of the disease—in which they were no doubt correct—such outrage arose among the people that many Jews were killed. This event is that reason that the Jews to this day are called microbes. For that reason, the Arabs understand especially well when likewise energetic measures are undertaken in Europe against the Jews and they are driven off like mangy dogs.

The speech continued with many Qur’anic exhortations and analogies that aren’t worth getting into here, even though they do a lot to challenge the notion that Jew-hatred in the Muslim world was a Nazi import. But it closed with the most important thing Amin al-Husseini had to say: the morally imperative prescription for the ills of all Arabs:

The Islamic world and the friends of Islam shall be shown how the Jews truly are in their innermost being. Usually, one only sees the Jews with the veneer of civilization, but the Arabs have learned best how they really are, that is, as they are described in the Qur'an and in the sacred scriptures. Then the agonies to which the Arabs in Palestine have been subjected can be understood. And one can imagine how these agonies will increase to the monstrous when the Jews have fully and completely laid their hands on Palestine. I present to my Muslim brothers in the entire world the history and the true experience which the Jews cannot deny. The verses from the Qur'an and hadith prove to you that the Jews have been the bitterest enemies of Islam and continue to try to destroy it. Do not believe them. They know only hypocrisy and guile. Hold together, fight for Islamic thought, fight for your religion and your existence! Do not rest until your land is free of the Jews.

This is not even the quiet part out loud. From this moment on, this was a central tenet to Hajj Amin al-Husseini’s definitive brand of radical Muslim and Palestinian nationalism, and a kind that sounds all too familiar to this very day.

However, rhetoric and ideas echoing across time is all well and good, but it doesn’t quite explain the most direct through-line that connects the Grand Mufti to events in the 21st century. There are certainly many examples one could use, but I don’t believe it’s unreasonable to use the decision made on May 17th, 1939 as the prime example. Lebanese historian Gilbert Achcar (hardly a Zionist-sympathetic scholar himself, and someone who believes al-Husseini’s influence is overrated, for what it’s worth) refers to this as “the major historical error of the Palestinian national movement.”

At this point, the Arab Revolt is three years old, and Amin al-Husseini is now in exile from his home (first in Lebanon and eventually in Iraq, the latter of which is its own sordid tale). The British, whose methods of crushing the revolt have taken on an eerily Nazi-esque character in which they made use of collective punishment techniques in Arab villages suspected of harboring combatants, were looking for a way to extricate themselves from this quagmire, with many likely aware of the increasing likelihood of war breaking out in Europe with Germany. There had been much debate circulating the halls of power as to how to solve this Arab-Jewish problem with a now-familiar term finding life for the first time in 1937: a two-state solution. This had been proposed by something known as the Peel Commission and it allotted what is today the West Bank and the Gaza Strip to the Arabs while giving most of the fertile coastline of Galilee to the Jews. The Arab nationalists under al-Husseini had quickly (and understandably) rejected this solution since it clearly showed preference. And while the two-state solution today is seen by many as the moderate, pro-Palestinian solution, at the time of al-Husseini’s rejection of this idea, it honestly made sense from his perspective to make this rejection. As historian Gilbert Achcar writes, “Acceptance of such plans would have been a dishonorable surrender. What people could allow a minority of settlers and refugees who had immigrated to its country, most of them within the past few years, to establish their own state on part of its territory?” It’s worth noting that while this logic may have made sense back in 1937, it makes far less sense now. Nevertheless, it’s still worth noting that a two-state solution was being proposed decades earlier than many might assume.

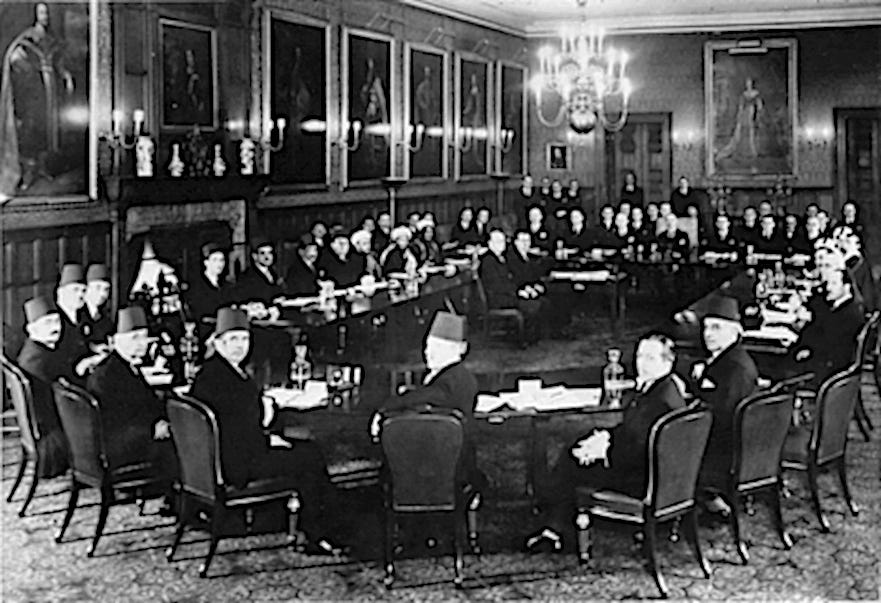

Now the Zionists, especially the hardliners, weren’t much happier with the idea of a two-state solution (again sounding quite familiar in the 21st century), though there was slightly more diversity in their reaction than in the Arab camp. But the point is that neither they nor the Arabs were all that fond of the Peel Commission. However, the Zionists would soon feel an outrage at the British Empire that, up until that point, only the Arabs had really experienced. That was when the infamous MacDonald White Paper was released by Neville Chamberlain’s government on the aforementioned date of May 17th, 1939. Largely drafted with stopping the seemingly non-stop avalanche of violence coming from the Arab camp in mind, the proposal was the biggest blow the Zionist movement had ever experienced. In his recent book Palestine 1936, political analyst and author Oren Kessler summarized the MacDonald White Paper as follows:

The statement announced unequivocally that it was not government policy that Palestine should become a Jewish state. Instead, the Mandate would be replaced within ten years by neither an explicitly Arab nor Jewish state but an independent “Palestine state,” accompanied by a treaty protecting the Crown’s strategic interests. Until then the country would move toward significantly greater local involvement in governance, and toward restrictions against land sales. As to immigration, the government could not accept the Arab demand for a total stoppage, which would prove ruinous to Palestine’s economy, Jewish and Arab alike. And it could not ignore the predicament of Europe’s Jews, which Palestine “can and should make a further contribution” to alleviating. Immigration, however, would no longer be open-ended. Rather, for the next five years it would be limited to the total figure stated at St. James’s— seventy-five thousand—and thereafter, only with the agreement of all sides. Without that consent, His Majesty’s Government would “not be justified in facilitating, nor will they be under any obligation to facilitate, the further development of the Jewish National Home by immigration regardless of the wishes of the Arab population.” Lastly, in place of [MacDonald’s] earlier “double veto” formula, the Arab veto now stood alone.

This was everything the Zionists did not want—the Jewish Agency referred to it as a “cruel blow” and “surrender to Arab terrorism,” and it is clearly easy to see why this was the case. It’s also easy to see, especially with the heavy restrictions on Jewish immigration (despite the obvious evil they were trying to survive in Europe at the time), and especially the unanimous veto power being given to the Arabs on internal matters, that it was, as best anyone with a working brain can see, exactly what the Arabs wanted. This was not lost on the Arab Higher Committee (i.e. the Arab Revolt’s ostensible political leadership), who were all gathered in the Grand Mufti’s Beirut home at the time of the White Paper’s release, and spoke excitedly about how everything had turned to their favor. Oren Kessler pulls from the recollection of a doctor named Izzat Tannous who remembered the following:

The morale was high and the expectation for a brighter future was higher. . . . But this sweet dream did not last long. The discussion became more strained as some of us began to realize that Hajj Amin was not in favor of accepting the White Paper. . . . The remaining fourteen members were not only strongly in its favor, but were determined to put an end to the negative policy the Arab leadership had been adopting heretofore. . . . Consequently, the sole concern of the Committee was now concentrated on convincing Hajj Amin that his negative stand was extremely detrimental to the Arab cause and was serving, unintentionally, the Zionist cause.

Somehow, for some reason, against all odds and logic and sense, Hajj Amin al-Husseini thought the only way forward was to reject this proposal, the best and biggest break his people had gotten for decades. In a sense, it was their own Balfour Declaration.

The mufti claimed that the White Paper had, as Oren Kessler puts it, “too many loopholes” and that “its transition period was too long, and its reference to the ‘special position’ that the future state would have to grant the Jewish national home was an insult.” Now, it is possible that al-Husseini was right to be so cynical; it certainly was, however perversely, understandable, considering all of the setbacks he had experienced, oftentimes thanks largely to Zionist Jews and the British Empire. But it’s also possible that we all live in a massive simulation being played by extragalactic alien teenagers. Just because something is possible doesn’t mean it’s likely. Kessler suspects, and for good reason, that the main reason the mufti didn’t take to the White Paper was thanks to his pride, since there was “continued British refusal to allow him a triumphant homecoming to Palestine.” Amin al-Husseini’s hunger for power and recognition was and remains well-known, but I think it is also clear that his true blind spot—his seething hatred of Jews—was affecting his judgment. And his decision driven by this compromised judgment would have effects that would outlive al-Husseini by decades.

Because the buck stopped with him on the Arab Higher Committee, the proposal was rejected one week later. The formal rejection read, in part, as follows:

The National Home has always been the fundamental cause of the calamities, rebellions, bloodshed and general destruction which Palestine has suffered. […] The Arab people have expressed their will and said their word in a loud and decisive manner, and they are certain that with God’s assistance they will reach the desired goal: PALESTINE SHALL BE INDEPENDENT WITHIN AN ARAB FEDERATION AND SHALL REMAIN FOREVER ARAB.

Within two years, Hajj Amin al-Husseini would be fleeing the Middle East to the safety of the Axis powers, whose goodwill—particularly that of the Nazis—he had been pursuing and cultivating since 1933, almost to the day that Adolf Hitler had taken office. He’d left nothing but wreckage behind him—particularly in Iraq, where his agitation had led to a coup d'état, war with Britain, and the eventual pogrom known as the Farhud that left hundreds of Jews dead and the Iraqi Jewish community—a largely anti-Zionist community—gutted forever. His influence would waver and diminish over the years, and while he would manage to allegedly be responsible for the deportation of several thousand Jews to Poland while knowing full well what was happening there, he would never accomplish much apart from becoming a personal friend of the Islamophile Reichsfuhrer-SS Heinrich Himmler and score an infamous (and overrated) meeting with Adolf Hitler in late 1941. He escaped a war crimes tribunal after the war and continued to fight to regain his influence in the Arab nationalist movement. When he came to Cairo in 1946, the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, Hasan al-Banna, gave him what scholar Jeffrey Herf termed “a hero’s welcome,” in which al-Banna proclaimed:

Hitler’s and Mussolini’s defeat did not frighten you. Your hair did not turn grey of fright, and you are still full of life and fight. What a hero, what a miracle of a man. We wish to know what the Arab youth, Cabinet Ministers, rich men, and princes of Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Tunis, Morocco, and Tripoli are going to do to be worthy of this hero. Yes, this hero who challenged an empire and fought Zionism, with the help of Hitler and Germany. Germany and Hitler are gone, but Amin Al-Husseini will continue the struggle.

However, after the Nakba of 1948, in which hundreds of thousands of Arabs were forcibly removed from Palestine, al-Husseini’s standing in the movement, and any meaningful influence he had, all but died.

That is, of course, except for Amin al-Husseini’s obstinacy; that remained alive and well. That, thanks largely to the standards and tone he set on that fateful day in 1939, as well as all of the downstream consequences of that decision—a decision no one else in his circle wanted to make, it should be remembered, including from some of the most hardliner Palestinian nationalists—didn’t just doom his cause. It was, in my opinion, the true clincher of these three root causes, the hinge point upon which the context created by the previous two root causes turned, and one that, had he not been the man he was or made the decisions he made, the long chain of pain and grievance that led to the slaughter of over 1,300 Jews in October of 2023 would, at the very absolute least, be much less likely.

…

There’s a certain emptiness that comes from learning of all these things, not to mention the many other things not covered here. Because there is a sense—a correct one, I should add—that knowing these things does nothing to solve the conflict. Knowing even more recent events—the ones more in living memory, from the Six Day War all the way until the election of Hamas in 2006—does just about as much. In truth, there is likely nothing that will solve this conflict, at least nothing with which the people most invested on either side of it will be happy. That’s the part I think that perplexes people to no end, even after learning all of what I’ve laid out here (and more). This is why it politicizes everyone it touches because, in the absence of obvious or certain answers, people will inevitably turn to faith, fantasy, and analogy in order to make sense of something that is largely driven by history—remember, a chain of pain and grievance—and incentives in which no one is wholly wrong or wholly correct. It’s why the most visible responses to what has occurred in and around Gaza for the last couple of weeks as of this recording have been so unhinged and detached from reality; they are merely proxies for previously held biases.

Look at it this way: the self-proclaimed anti-imperialists see George Floyd when they think about Gaza and her people, pinned to the ground, his life being crushed within his windpipe, begging for his mother. Zionists see Michael Brown, charging at Darren Wilson, the police officer handling the incident after having attempted to wrestle his weapon away from him. In both of those scenarios, there was one clear victim and one clear aggressor. When you reduce complex geopolitical circumstances so deeply steeped in very violent history like this, it can make sense to see why there might be people getting so upset about the deaths of Palestinians or Israelis, but only exclusively. But honestly, that does little to explain how things exist between these two peoples.

I’ve tried to come up with my own analogy to explain the relationship between the Israelis and the Palestinians across the last century, but I still have yet to come up with one better than one than the analogy offered by Darryl Cooper of the MartyrMade and Unraveling podcasts and I sincerely hope he doesn’t mind me borrowing it; it’s just too apt not to use. In his analogy, he describes a man having leapt from a burning building on the fourth floor. He comes crashing to the ground, his fall only broken by landing on top of another guy. The second guy is pinned below the first guy and is understandably infuriated at what just happened, since he never asked to be hit and pinned by a falling a person (a person who only fell in order to escape a fatal blaze, remember). Because he’s angry, the pinned man starts thrashing to get out and the man who’s pinning him tells him to calm down for a second, but this just makes the pinned man angrier and he starts swinging around a knife. Now the man doing the pinning has to deal with the consequences of letting this guy beneath him get up, even though by all rights he should not be pinning this man to the ground on whom he just crushed.

How does anyone extricate themselves from a situation like that? Especially without someone—either one of the combatants or even a bystander—getting hurt, or worse? I don’t have an answer. And I’ve found that the more people study this conflict, especially its root causes (even when it’s only three of many, many more), the less satisfying the answers will be and the more likely those who know these things will nod sadly in agreement. In a way, perhaps learning about and even debating the root causes is all we can do; we can prevent ourselves from turning thousands of lives, etched in the most abject of human suffering, into the proxies for our luxury beliefs. Perhaps we can then at least retain a little dignity as we delay the inevitable, when the pinned man and the man who is pinning him both finally decide to stand up and make their next, perhaps final moves.

I am sitting with my partner of 13 years and she is remembering the arrival of her paternal grandmother to Ellis Island exactly 100 years ago today. She and her sister joined their Rabbi father just before the closing of the US borders to most immigration. It is interesting to look at our histories to see what choices/happenstance that led us to live under the same roof. Your description of Russian pogroms covers part of her story, while mine was partially captured by JD Vance's ill conceived Hillbilly Elegy. It is my contention that equal opportunity to an excellent education levels most of the playing fields.

While I appreciate the grand history and it certainly helps understand why things are said and done by each side, I would really like the media/historians to look at some of the other potential issues that drove some of the barbarity that bubbles up through history. It's pretty clear to me that some of the worldwide violence that began to rise after WWII can be tied to mass lead poisoning of the populace due to expansive use of leaded gasoline. There are other agents that are purposefully used to drive hatred and separate man from his humanity and seemingly one of these agents are man made drugs derived from ephedrine. Reportedly Hamas was using a similar drug in their training methods just like the Nazis and the Japanese. In addition, Meth in this country leads some people to have absolutely zero humanity for other humans. When the media equates Hamas trained fighters to justify killing Palestinians that live in fear of what I suspect are violent religious junkies it reminds me of the stupid decisions made by the US in the aftermath of 911.

History matters, especially the history of the last 120 years, but that history has to be told that includes all the factors that may lead to violent outcomes. I am not sure we are there yet, but your 3 causes are enlightening.

I could wax on about Darrell Cooper, Mike Brown and George Floyd as these figures tell a story but not the one that gets the story "more correct" Thanks again.

I had some killer timing and stumbled upon your work. I had just wrapped up episodes 1-5 of nazi Muslims just a week before the attack on Israel. I guess one point I would like to make is this is war and it sucks but I am really having a hard time finding any sympathies with the Arabs in that neck of the woods. I want to refuse to call them Palestinian because there is no historical record of a Palestinian state or people. Sounds brutal I know but it’s my understanding there just isn’t. There were some tribes of Arabs but I really believe they are an invented people. They are people so don’t get me wrong but they are getting what they wanted in Hamas. Did we run constant body counts on the dead Hitler youths and citizenry? You know the answer to that but what is going on right now blows me away. These are the modern day Nazi! They want every Jew to burn basically, it’s in their charter. And the nonsense that it’s not all of them is ridiculous. Where are all these moderates when the bombings and killings are not happening? I’m sorry these people do don’t want to coexist in the slightest. There will never be a two state solution. That’s pie in the sky.