On November 7th, 2024, disturbing footage began to appear in the aftermath of a football (soccer) match between the Israeli club Maccabi Tel Aviv and the Dutch club AFC Ajax. Unlike your typical stories of football hooliganism, the fight was not over the outcome of the match (Maccabi Tel Aviv lost, for what it is worth) as much as it became another proxy for the ongoing war between Hamas and Israel. Groups of men were roaming the streets, accosting fans of the Israeli team, and beating them where they found them. One Israeli was captured on video pleading, “Not Jewish, not Jewish!” as he was assailed. David de Bruijn summarized some of the violence quite well in his write-up for The Free Press as follows:

In video of other attacks last night, a victim is struck and lies injured on the ground, seemingly unconscious. A father can be seen fleeing with his son. A man jumps into one of Amsterdam’s canals to escape his assailants. In the recording, where he is forced to say “Free Palestine,” his assailants laugh and jeer that he is a “cancer Jew”—a classic slur in Dutch, where both diseases and the Jewish ethnicity are deployed as put-downs.

While the chaos unleashed by football hooliganism is well-known, it would turn out that evidence suggested this was something else. As more became clear in the day that followed, it became obvious that this was a coordinated attack on the Israelis visiting the Dutch capital. According to an investigation conducted by The Telegraph, it “emerged that the attacks on the Jewish football fans were planned in advance and coordinated using WhatsApp and Telegram.” The day before the match, a group chat called “Buurthuis” contained the chilling phrase: “Tomorrow after the game, at night, part 2 of the Jew Hunt. Tomorrow we work them.” Put simply, in the words of de Bruijn, “According to the accounts of witnesses and victims, it was an attack by immigrant, Muslim communities against Israelis and Jews.” A pogrom, in a European city, committed by descendants of migrants from the Middle East and North Africa, is not likely what Adolf Hitler had in mind when he declared war on “world Jewry,” but it is hard to believe he would not have been pleased to see those he saw as racial untermenschen doing his work for him.

Soon, further potential context was added—that there was some vandalism and outright hooliganism from some of the Israeli fans, including ripping down Palestinian flags, as well as expletives being shouted by Israeli fans (i.e. “Let the IDF win, and fuck the Arabs!”), and some assaults captured on video by the Dutch photographer Annet de Graaf (which were initially misattributed to Arabs attacking Israelis). However, in addition to this not being particularly exonerative of the initial plans for a “Jew hunt,” much of this supposed context was not being repeated as an effort to provide a clearer picture of that night’s events. Rather, it was repeated by pundits and publications with motivated reasoning. The delight clearly underlying the performative outrage by professional distorters of history like Owen Jones was actually quite palpable, with Jones describing Sky News’ re-editing of their footage to more accurately reflect the reality as being the real problem along with “the violence perpetrated by Israeli football hooligans, and their hideous racism.” Medhi Hasan (who the real mensch Representative Ritchie Torres repudiated beautifully) seemed like he wanted to try and one-up the whataboutism and quote-tweet President Joe Biden, saying that the President’s legacy will be that “you and your administration that helped kill 16,000 Palestinian kids.”

There were plenty of other examples of this kind of redirection at work in the days that followed, and they reveal the same trend: that instead of trying to dig out the overall, complex truth that led to, yes, a modern day pogrom, there was an effort to whitewash the systematic targeting of Jews in a Western European country for violence. Much seems to rest on the use of the word “pogrom” to describe what happened, with many of the commentators in this camp seeming to believe that a pogrom requires a perfectly lop-sided situation in which the victims—Jews in this case—are viciously set upon with no attempt at defending themselves or they themselves playing a part in the violence in general. Not only does this smack of the problematic trope about Jews not fighting back in the Holocaust being one reason so many were killed, but it also forgets that fact that one of the most savage pogroms against Jews in the early 20th century—the Hebron riots of 1929—also involved Jews (and non-Jews) fighting back against the mob that was obviously targeting them. The contrarians, in this case, seemed to be upset that the pogromists were facing victims that did not act like victims of a pogrom in the “correct” way.

The bigger question, however, is “why?” It makes a certain amount of sense that some people who already oppose Israel on grounds that the IDF is killing members of their family. However, there are and have been no shortage of people who, for over a year, rush to explain away or even defend things like this (e.g., the Dagestan attempted pogrom, the student incident at Cooper Union), and have zero meaningful connection to the ongoing conflict seemingly apart from a vague notion of political solidarity. It has vexed a lot of people, including me, for years now, why there appears to be an almost reactionary need by a certain section of the Western left (and increasingly, it seems, the right, but that is a different story) to stand in solidarity with self-evidently problematic movements and even defend their actions. What happened in order to make this kind of defense of something that most people have known for decades was objectively wrong and evil into something that somehow needs to be debated? We saw this happen in the wake of Charlie Hebdo, the Pulse Nightclub massacre (which turned out to likely have nothing to do with homophobia), and other things that involved this same kind of extremism associated with a very particular religious ideology. But why?

Many have problematically stated or suggested that the spread of Islamic communities in Western countries is leading to a sort of “subversion” of Western values, particularly in Europe (though this thinking arguably helped result in the United States’ own “Muslim Ban” in 2017). However, this is usually filtered through the lens of anti-immigrant sentiment and, perhaps, a subconscious throwback to post-9/11 anxieties about terrorism. When one sees growing crowds of decidedly non-Sven-looking people rushing around the streets of Amsterdam trying to hunt down Jews to hurt, it might seem to be completely reasonable to feel that way. After the migrant crisis in Europe in 2015 and the subsequent tensions (and crimes) that occurred, anti-immigration sentiment certainly rose and felt justified to many, regardless of political ideology, especially as the years went on. However, that does not explain the willingness of certain classes of people willing to go to bat for bad behavior on the part of foreign actors (or domestic ones acting on behalf of a foreign cause). What does seem to explain this trend, among many factors that have already been examined, is not an importation of people, but rather, an importation of ideology. In other words, an act of subtle imperialism.

…

Probably one of the most shocking things I learned during my first year of graduate school was that Jackson Pollock was a stooge for the CIA.

You read that right.

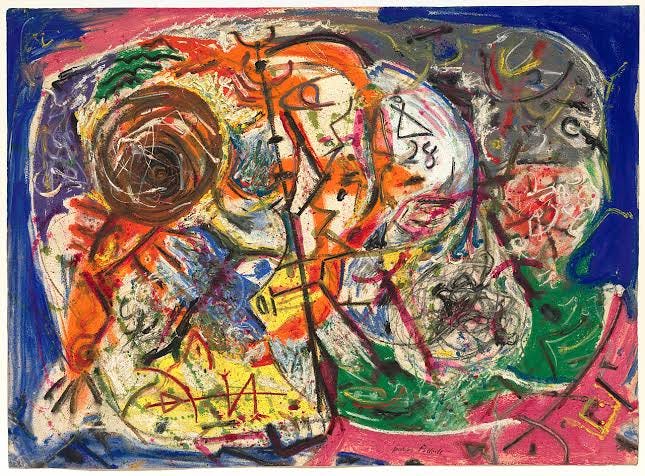

I do not mean to say that Pollock, one of the most celebrated Modern artists of the 20th century, was an assassin or international super spy for our most infamous of alphabet agencies, but rather, the success of his work was, in fact, due in part to an enormously successful propaganda campaign developed by an organization that was a front for the CIA. Some background is likely in order.

You see, what we see as a free-wheeling, earnest and yet somehow ironic epitome of pretension—that is, Modern art—was never going to stand a chance without a little boost from Uncle Sam. At least, that is what figures linked to both the art world and the world of covert intelligence believed at the height of the Cold War. Technically, this effort began during the Second World War, in an effort to combat the aesthetics of Nazism, but once Hitler and his regime shuffled off this mortal coil and Stalin and his mega-empire revealed itself as the true nemesis of our age (and unlike most people who have written about this subject, I say that without any irony), the effort to promote American values in contrast to Soviet ones by any means necessary took on a stark meaning. As Lucie Levine wrote in a 2020 article for JSTOR Daily, “Modernism, in fact, became a weapon of the Cold War.” Continuing, she writes:

In the battle for “hearts and minds,” Modern art was particularly effective. John Hay Whitney, both a president of MoMA [the Museum of Modern Art] and a member of the Whitney Family, which founded the Whitney Museum of American Art, explained that art stood out as a line of national defense, because it could “educate, inspire, and strengthen the hearts and wills of free men.”

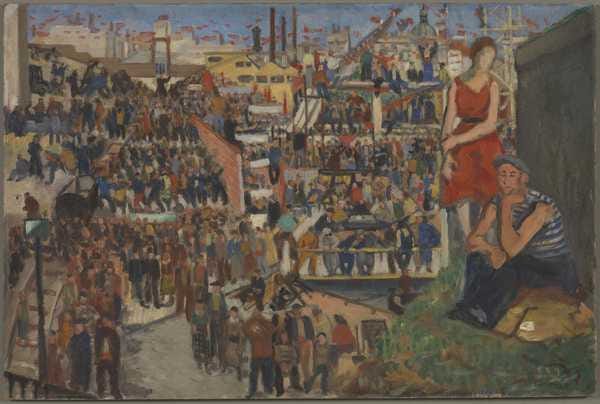

This mission of using Modern art to essentially propagandize the world with American values was essentially gifted to the United States by Soviet propaganda which repeatedly claimed that thanks to our love of capitalism, our nation was “culturally barren.” Their contrast—that is, Soviet realism (which, at least in my opinion, has some kitsch charm)—was not exactly setting the world on fire, but their claims about the United States made a propagandistic response relatively easy. In 1946, the U.S. State Department spent almost 50,000 dollars (almost 850,000 in 2024 money) on paintings by the likes of artists like Georgia O’Keefe and included them in a traveling exhibition known as “Advancing American Art.”

The exhibition did well in much of Europe, but the Americans who saw it were embarrassed. Modern art was not the most popular medium for self-expression in the immediate postwar United States. Look Magazine even wrote a piece called “Your Money Bought These Paintings,” expressing outrage that taxpayer money funded such a project (because it’s important to note that the State Department’s involvement was no secret). Politically, the exhibition was a sham on both sides of the aisle—both Harry Truman lambasted the artwork as anything but, and Republican Congressmen John Taber and Fred Busbey expressed concern that the artists whose work had been tapped had communist sympathies. Ironically, in perhaps every sense, this was why the artists—as well as later ones like Pollock—were perfect subjects for the mission of spreading American values (or, perhaps more accurately, vibes). As Lucie Levine writes:

The American public’s fear of the Red Menace brought “Advancing American Art” home early, but it was precisely because Modern art was not universally popular, and was created by artists who openly disdained orthodoxy, that it was such an effective tool in showcasing the fruits of American cultural freedom to anyone looking in from abroad.

Because the State Department’s involvement in the Advancing American Art exhibition is what made this a matter of public record (and admonishment, thanks to its use of taxpayer dollars), it quickly became clear to America’s Cold Warriors that doing things like this would require Congressional approval, and that was a hurdle they just couldn’t bring themselves to accept. This was where the CIA, not exactly known for its propensity to ask permission to do pretty much anything it has ever done, came into the picture.

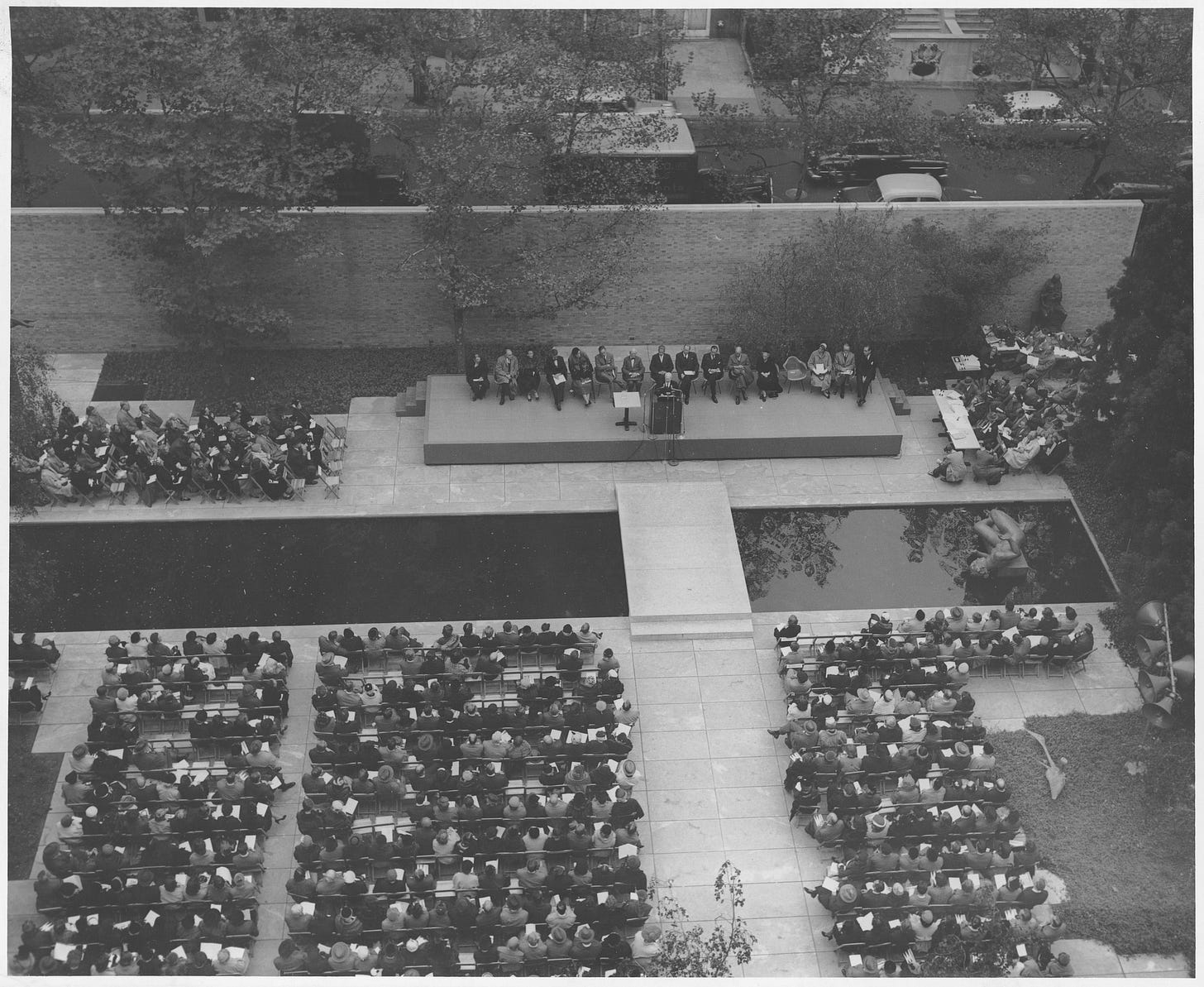

The history of the CIA—an outgrowth of the Office of Strategic Services during the Second World War—is fascinating enough on its own, and has provided enough grist for an untold number of books and excellent films like Robert De Niro’s 2006 epic, The Good Shepherd. It is definitely something into which I want to dive with greater depth in the future, but the important point to remember is that, codified into law in 1947, the CIA grew up with the Cold War; one could even call it its fraternal twin (or perhaps vestigial twin). There is no CIA without the Cold War, in other words (though one could also say there is no Cold War without the CIA). There was also no connection between Modern art—remember, not traditionally beloved by the establishment or even the broader public—and American values without a certain president: Dwight D. Eisenhower. Recognizing the ideological value in a medium so American in its essence as Modern art, President Eisenhower served as a speaker at the 25th anniversary celebration for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1954, and said the following:

As long as our artists are free to create with sincerity and conviction, there will be healthy controversy and progress in art. How different it is in tyranny. When artists are made the slaves and tools of the state; when artists become the chief propagandists of a cause, progress is arrested and creation and genius are destroyed.

This was as close to a public declaration of official policy toward the government sponsoring artists to spread the American way abroad to counter Soviet tyranny as American citizens were ever going to get. Four years earlier, in 1950, the CIA had established a front organization known as the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), which was, far from Washington D.C. (or, as of 1961, Langley, Virginia), situated in the (perhaps former) cultural capital of the world, Paris. With the aim of “propagat[ing] the virtues of western democratic culture,” through the use of an “autonomous association of artists, musicians and writers,” in the words of historian Frances Stonor Saunders, this office operated for nearly two decades. As Saunders continued in her 1999 work, Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War:

[The CCF] had offices in thirty-five countries, employed dozens of personnel, published over twenty prestige magazines, held art exhibitions, owned a news and features service, organized high-profile international conferences, and rewarded musicians and artists with prizes and public performances. Its mission was to nudge the intelligentsia of Western Europe away from its lingering fascination with Marxism and Communism towards a view more accommodating of “the American way.”

The CCF was not about convincing the American public to suddenly like Modern art. Rather, it was to convince European cultural skeptics of America’s ability to create Modern art, and thus sway them away from any possible Soviet influence. In other words, the CCF, under the direction of the CIA, attempted to woo fence-sitters away from the evils of communism by showing them weird, transgressive, and ultimately individualistic art. In other words, the antithesis of collectivist communism.

The biggest and best irony—and perhaps the one most relevant to the broader story we’re looking at today—is the fact that these moves by the CIA via the CCF were aimed at the European left; that is, socialists, leftists, and other parts of the anti-totalitarian left in Europe (i.e. the place that George Orwell might have still occupied, had he not died in 1950). This can be seen in the CIA funneling money into the United States’ own anti-communist leftist publication, the Partisan Review, which actually had published Orwell, as well as T.S. Eliot.1 As American journalist and CIA official Thomas Braden explained the program and the thinking behind it in the Saturday Evening Post in 1967:

Back in the early 1950’s, when the Cold War was really hot, the idea that Congress would have approved many of our projects was about as likely as the John Birch Society's approving Medicare. I remember, for example, the time I tried to bring my old friend, Paul-Henri Spaak of Belgium, to the U.S. to help out in one of the CIA operations.

Paul-Henri Spaak was and is a very wise man. He had served his country as foreign minister and premier. CIA Director Allen Dulles mentioned Spaak's projected journey to the then Senate Majority Leader William F. Knowland of California. I believe that Mr. Dulles thought the senator would like to meet Mr. Spaak. I am sure he was not prepared for Knowland’s reaction:

“Why?” the senator said. “The man's a socialist.”

“Yes,” Mr. Dulles replied, “and the head of his party. But you don't know Europe the way I do, Bill. In many European countries, a socialist is roughly equivalent to a Republican.” Knowland replied, “I don't care. We aren't going to bring any socialists over here.” The fact, of course, is that in much of Europe in the 1950's, socialists, people who called themselves “left”—the very people whom many Americans thought no better than Communists—were the only people who gave a damn about fighting Communism. [Emphasis added]

CIA stooge or no CIA stooge, Braden was spot on in his assessment of who was both a.) the most valuable in Europe when it came to the intellectual fight against communism (instead of the military one), and b.) who was the most vulnerable to such invitations (or aesthetic provocations; your mileage may vary). This vulnerability is key to understanding the central concept of American cultural power during the height of the Cold War, most certainly; but it is also key to understanding a deeper, far more relevant form of empire that actually has history stretching back well over a century, and, more to the point, the primary type of empire (and imperialism) that exists moving into the 21st.

This is not to say that “classic” imperialism does not still exist, and cause untold amounts of damage. Russia’s nearly three-year-old war with Ukraine, however you want to define NATO’s role in it, was, without question, an act of flagrant territorial imperialism. One can also reasonably make the argument that there is a form of commercial imperialism—perhaps even a sort of neo-colonialism—occurring in Africa, especially the Democratic Republic of the Congo, under the auspices of massive Chinese corporations (and to the massive benefit of the United States, especially in the tech sector, as documented poignantly by Siddharth Kara in his 2023 book, Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives). However, the most common form of what could be called “imperialism” in the 21st century is one that exercises a softer touch; “soft power,” is the colloquial term in the history of international relations. Common though it certainly is in the 21st century, it is actually a much older practice; the only difference between soft power now and soft power, say, 200 years ago, is that it spreads much faster and easier than it used to, thanks to the quantum leap of communications technology. However, we should not underestimate the power, persistence, and application of soft power in our past, even though it was moving at the speed of a steamship instead of the speed of light.

Historian David Todd explores this concept in the context of French history with what he calls their “velvet empire,” a much more informal system of culturally-derived power than the Napoleonic image that 19th century French imperialism tends to conjure. Todd’s point is to suggest that this approach was no less effective than formal control, and indeed, France developed a stronger global presence through their influence. As Todd writes, “[France in the 19th century] deserves to be considered an empire [...] because it combined wealth-extracting practices with claims to universal dominion, and because it affected the economic life of millions of men and women.” Todd makes the United States comparison explicit as well, pointing out that the French velvet empire’s “sophistication prefigured, in some respects, the global projection of American ‘smart power,’” with its “blue jeans and sentimental movies.”

What the French accomplished overseas after the Napoleonic era does, in fact, share more with the United States in the 20th and especially 21st centuries, than any other imperial power of the modern era. The French velvet empire had, as Todd puts it, “a preference for a soft and concealed style of domination and [a] specialization in the procurement of conspicuous commodities.” For the French, this meant everything from silk to champagne, with the latter example’s legacy being acutely felt every time you make the mistake of calling sparkling wine “champagne” and have a pretentious twit swooping in to correct you that champagne is only champagne when it comes from grapes grown in that particular region of France. Annoying, to be sure, but also accurate; and, more importantly, evidence of lasting cultural power projected very deliberately by French commercial interests and allowed (if not megaphoned) by their government. This was not lost upon the contemporaries of the French velvet empire. As Adolphe Blanqui (who Todd refers to as the “disciple” of famed French economist Jean-Baptiste Say in promoting what Todd calls “French champagne capitalism”) said of the Crystal Palace exhibition of 1851:

All the products, wherever they came from, looked common and provincial when compared to those of France. [They possess] elegance, grace, and je ne sais quoi. […] [The exhibition of Lyon silk textiles of] plain cloths, cut or primped velvets, taffeta, satins, and gros de Naples [plain stout silks], crapes, plush, scarves, dobbies [patterned fabrics], brocades, church, or palace cloths […] is very dangerous for husbands. From the morning to the evening, thousands of ecstatic women jot down in their notebooks [the names and addresses of French manufacturers].

The point being made by Blanqui (and a century and a half later by Todd) is clear: the perception of French commodities by the mid-19th century had become perfectly tied to notions of high class and refinement. Post-Napoleonic French imperial influence, however soft, was secure for the foreseeable future, and all they had had to do was make the rest of the world buy into the vision of refinement that they had sold them.

Todd is careful to note that the terms “empire” and “imperialism,” in this case, are not used in a pejorative way, while also acknowledging that the distinctiveness of soft and hard imperial power throws his entire thesis into question. After all, should we call global capitalism—and that is what this is—a form of empire? Empire may be a neutral term by definition, but it is hardly neutral in almost every instance of it being used. We can thank Star Wars for that, as well as hundreds of years of human history, with its more extreme examples like the Third Reich’s genocidal push to the east or the horrors of the Belgian Congo. The sticking point is the question of coercion, which is usually what gives people the reflexive gag when they think of empire; after all, is coercion not a feature of imperialism? Not necessarily. As Todd writes:

Empires are rarely, if ever, entirely coercive. Even the most formal of colonial ventures, the British Raj in India, relied extensively on indigenous collaboration, while British settler colonialists have been described as “pre-fabricated collaborators” of imperial rule. From this perspective, informal empire is merely a system of collaboration that leaves intact the external layer of sovereignty of foreign, colonized states.

However, none of this is to say that empire is ideal, especially for those not at the helm of the empire itself. This is especially the case if the external power seeks to do more than engage in global trade, which tends to benefit everyone (though rarely in equal terms, of course). This is to say that intent matters, and if the intent is to do more than simply spread the prestige and appreciation of your culture through your products and services—as the French, in part, did; this is putting aside the violence they perpetuated in Algeria or Indochina, of course—then this is where the self-evident problems of imperialism begin to appear.

A good example of this is the spread of European colonists in the New World hundreds of years ago; many Indigenous tribes had no problem engaging in trade with these strange newcomers once communication became less of an issue. But when the colonists began trying to force the tribes into communion with their god instead of letting them believe in their own gods, the reality of the situation likely set in for a lot of them (and this is to say nothing of the “hard” power that was used against them, as it often was). In other words, “soft” imperial power may not be inherently coercive, but it does not take much for it to become so, or at the absolute least, be perceived to have become so.

This is all to say that imperialism has always been more complicated in its use of formal and informal control methods, but as time has gone on, with only a few exceptions in the 21st century, much of the imperialism we see has more in common with how the French began to do things in the mid-19th century: hands-off, distant, cultural, with a soft, velvet touch. And yet, we must remember, however soft imperial power may be, it is still imperial power.

…

So what does all of this have to do with Islamism? To explain, a concrete definition of Islamism is first in order. Put simply, Islamism is typically a militant and political manifestation of a particular kind of Islam, one strictly informed by the tenets of sharia law. If one needs a more Western comparison, it is essentially the Islamic version of what people mean when they say “Christian nationalism.” Like the idea of Christian nationalism, there really is not one singular expression of Islamism—it has variants depending on time, place, and even leadership. Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia is a form of Islamism, for example; so is the ideology of major terrorist organizations, including Hamas, which one could more accurately call jihadism. There are also far more moderate (that is, compared to a group like Hamas) individuals and organizations who might be classified as “Islamist” as well, including Bosnia’s Party of Democratic Action (SDA) and the Turkish politician Merve Safa Kavakcı. It is important to point out these more moderate examples because Islamism, like I said above, can differ in some ways from culture to culture. Bosnia’s SDA, for example, is certainly informed by religious adherence and conservative values, but it is more defined by its nationalistic character, making more particularly Bosnian than it is Islamist.

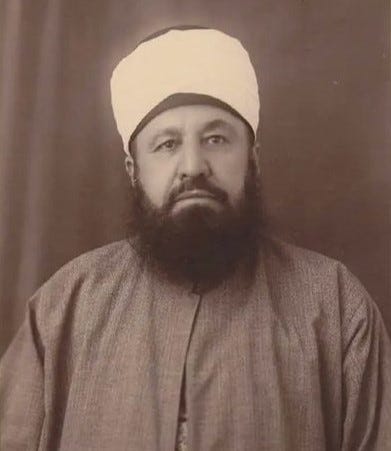

However, Islamism’s most visible and controversial (to put it mildly) manifestations are very much tied to the ideologies that have come from the Middle East. Islamism was borne from something of an Islamic revival that took place in the early 20th century after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey’s turn toward a more secular approach to governance, like its ostensibly Christian counterparts in Europe and the United States. This created a reactionary backlash in many more radical corners of the Islamic Middle East, which became characterized by a fundamentalist zeal and militant adherence to the Qu’ran and hadith (also known as Salafism, at least in the Sunni context), as well as a knee-jerk rejection and even hatred of anything associated with the West and, as the 20th century progressed, the Jews and Israel. This is where things might start to sound familiar to long-time listeners of History Impossible, because this was the political hotbed for the future Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and the father of the organized Palestinian nationalist movement (and Nazi collaborator) Hajj Amin al-Husseini.

As I have covered in past episodes of History Impossible, Hajj Amin cut his teeth on this stuff at Al Azhar University under the tutelage of the early Islamist scholar and ideologue, Muhammad Rashid Rida. Rida was nothing if not a hardcore revivalist, something akin to a 20th century Egyptian version of Jonathan Edwards or George Whitefield, and he quickly developed a following of students that included people like Hajj Amin al-Husseini. Rida’s teachings, which could be seen in his publication Al-Manar, was likely one of the major origins of Hajj Amin’s own antisemitism. In the years leading up to the First World War, Al-Manar was actually publishing article after article accusing the Jews of being the puppet masters of European finance and empire, as shown by scholar Neville Mandel. If this was not clear enough, Arab nationalists did not need the Nazis, the British Empire, nor even the Zionist project’s incursion into Arab lands to become your typical and recognizable antisemites.

However, the antisemitism present in Islamism is merely one feature among many, and far from the most significant when discussing Islamism in the context of empire. This is because at its core, Islamism is what we today could call a kind of “MAGA ideology,” in the sense that it fixated (and continues to fixate) on a mythical past where Islam dominated the land and all was greater than it is today. This, like the essence of MAGA-adjacent rhetoric in its own way, was an understandable view for someone dedicated to Islamic greatness to feel in the early 20th century, especially in the 1920s with the decline of the last Islamic empire (that is, the Ottomans) to the forces of Western secularism. However, this manifested in the outdated and logistically impossible ambition of restoring the caliphate, or an Islamic empire. Fantasies of rebuilding fallen empires was nothing unique among reactionaries and conservatives in the immediate aftermath of the First World War and Bolshevik Revolution; Rashid Rida’s fantasies were not dissimilar from the empire rebuilding messianic delusions of figures like Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, i.e. the Bloody White Baron.

In Rida’s vision, laid out in his book Al-Khilafa aw al-Imama al-ʿUzma (The Caliphate or the Supreme Imamate), an Islamic caliphate—not necessarily a Turkish/Ottoman one, but that was the most recent model—would be restored, in which authority would be delegated by Islamic jurists. The long-term goal would be a perfect, strictly Islamic society, which would serve as a model for further Salafist-minded reform in all corners of the Muslim world (e.g. Islamic societies like Indonesia, Malaysia, and places at the time occupied by the British and Soviet empires, like Kazakhstan and India). In essence, Rida was calling for an Islamic supra-state, utopian in form almost like that of so-called “world communism,” in which the word of Allah would be supreme and the authority of Christians, capitalists, and communists would wither away. As historian John Willis has written on this, “[Pan-Islamism] was a response to the crisis of legitimacy in the international state system in the early twentieth century. In this view, Pan-Islamism was part of a wave of international movements including Bolshevism and Pan-Asianism that sought to create an alternative to the nation-state and the post-Westphalian international order.”

Islamism (largely synonymous with “Pan-Islamism” in this context) has gone through a number of variations since Rida laid his ideas to paper, including Hajj Amin al-Husseini’s own interpretation of a restored Caliphate operating with Palestine (and thus Hajj Amin) at its center, something we have discussed before on History Impossible. But regardless of where the hypothetical Caliphate would be centered, there was always one constant: a restoration of the Caliphate, and new moral order enforced by the sword, was the ultimate goal. Sometimes it would manifest in harder, more militant ways, including through the writings and teachings of Sayyid Qutb, which inspired Osama bin Laden. And other times, it would take a softer, supposedly more reformist route. The militant, often called jihadist route, is well-worn territory and one that requires little unpacking for the purposes of this essay; we all know what jihadism is and how it manifests and need little in the way of reminder. It is the softer power that concerns us here. This is because whether it is soft power or hard power, at its shared cross-cultural core, Islamism’s ideology is an expansionist one and one, like that of harder jihadism, that will not rest until the so-called “House of Islam” triumphs over the so-called “House of War.” This principle is laid out very concisely by the late Orientalist historian Bernard Lewis in his excellent book, The Crisis of Islam:

In Muslim tradition [as recognized in stricter militant forms of Islam], the world is divided into two houses: the House of Islam (Dar al-Islam), in which Muslim governments rule and Muslim law prevails, and the House of War (Dar al-Harb), the rest of the world, still inhabited and, more important, ruled by infidels. The presumption is that the duty of jihad will continue, interrupted only by truces, until all the world either adopts the Muslim faith or submits to Muslim rule.

This explanation more directly refers to jihad, that is, “the armed struggle for the defense or advancement of Muslim power,” but it is indeed important to remember that the desire for Islamic dominance is by no means limited to violence. In fact, violence is relatively rare by all metrics and generally not supported by most Muslims, to say nothing of the rest of the world (i.e. the “House of War”). This is why the more sophisticated among history’s Islamists have always understood this and have thus always defaulted to softer means of spreading their influence.

Softer Islamism is more political in nature, but no less problematic, at least by Western democratic standards. Again, the most helpful analogue is the aforementioned frequent bogeyman that is Christian nationalism.2 Non-jihadist, non-violent Islamism is still relatively extreme, politically speaking, because of what its ultimate end goal typically involves: a restoration of a theocratic empire. While the libertarian impulse is, in a vacuum, the correct one—that is, if Islamists in, say, the Middle East, want to engage in a politics that results in a theocratic empire, more power to them, since that has nothing to do with us—in practice, especially in the early 21st century, it is not that simple. In fact, we have seen quite the opposite of play out, both in the United States and more problematically, in Europe. In essence, Islamism is something many in the West would typically recognize as inherently illiberal and something we would not want to see our own religious fundamentalists doing abroad. That is, because it is a form of soft (that is, cultural; or like France in the 19th century, velvet) imperialism.

Just as post-Napoleonic France did not focus on territorial conquest as much as cultural influence, soft-power Islamists in the modern era see very little value in violence and, in fact, often see violence as counter-productive to the ultimate goal of Islamic dominance. However, it is important to recognize that this notion of Islamic dominance is not necessarily universal; as suggested by Bernard Lewis’ earlier explanation, submission is perfectly acceptable in lieu of conversion. While there are certainly Islamists who might believe it would be nice if the West became a uniformly Islamic place, that is rarely, if ever, the immediate goal of Islamist activist groups operating in the West. In the most general terms, the goal of these organizations is to make aspects of Islamic-inspired dominance and values seem anodyne if not preferable to what currently exists; that is, liberal democracy and free market capitalism. When looking at it this way, it becomes less seemingly bizarre that pro-social justice activists and seemingly secular leftists in the West link arms with Hamas and other supposedly anti-colonial groups; in hatred of capitalism and liberalism, there is very little daylight between these two classes of activists. This is something of which many Islamist groups like to take advantage because, like any rational actor, they seek any advantage they can use.3

In the modern era, Islamist groups’ values and tactics are under the protection of speech laws in the West (particularly the United States). However, the speech in which these groups engage is not necessarily what matters. It is the international associations that tend to give the game away about what the goals of these groups entail. As an example more directly tied to recent events—namely the Israel-Hamas War—there is American Muslims for Palestine (AMP), which was placed under investigation in 2023 by the Attorney General’s Office of Virginia for possibly funneling money to Hamas. Similarly, the Muslim American Youth Association (MAYA) has its own problematic ties; according to a 2010 report by the FBI, “[The Muslim American Youth Association] served as a conduit for money to Hamas through the [Holy Land Foundation] and served as a forum where Hamas could promote its ideology and recruit new members.” The Holy Land Foundation (HLF) mentioned in this report is also worth scrutiny in this context because its ties to Hamas, which have likely existed since 1988 when both organizations were founded, have led to legal trouble for the organization in the past. The same FBI report lists the HLF as “the financial arm of HAMAS within the United States,” proven by documents seized in a raid on the home of a one Ismail Selim Elbarasse, who was arrested in 2004 for his fundraising activities for Hamas via the Muslim Brotherhood.

It is clear that these organizations appear to have missions more dedicated toward supporting the Palestinian nationalist cause than to the restoration of a caliphate, though it is important to remember that, at least according to some radicals following the lead of Hajj Amin al-Husseini, Palestine has frequently been seen as the center of that dreamed-of empire; it is also important to remember that the Muslim Brotherhood, an international organization that lives at the center of most Islamist causes, was co-founded by Hajj Amin and like any Islamist organization, yearns for a caliphate as one of their stated aims. That is unlikely to be the explicit goal of these organizations or even of the individuals working within them. However, Palestine serves as the best entry point into Western politics with Islamist organizations. After all, there are very few, if any, causes related to the Muslim world about which Westerners have even an inkling of awareness. It is fair to say that most Islamist organizations are fully aware of this.

One of the most famous international Islamist organizations is Hizb ut-Tahrir (HT), well-known thanks to its most famous (or infamous) defector, Maajid Nawaz. Regardless of how one feels about his post-COVID populist turn, Nawaz has written extensively about his exit from the organization and, as he sees it, the threat Islamism poses to the West. In 2009, Nawaz, a British-born Pakistani Muslim, returned to Egypt where, a decade before, he had helped inculcate what he called in one of his columns, “Islamist fever.” HT has been around since 1953, when it was founded in East Jerusalem, Jordan, and has since expanded to include members in over 50 countries. It sports an estimated membership that ranges from tens of thousands to over one million; the truth is, no one really knows. Like most Islamist organizations, it has ties to the Palestinian nationalist movement, but it takes a broader view in its vision of a world dominated by an Islamic empire. Following the lead of its founder, the Palestinian Islamic scholar and early pan-Islamist Taqi al-Din al-Nabhani, HT’s stated aims include not just the usual restoration of the caliphate, but also expand that caliphate into non-Muslim areas; that is, to expand the House of Islam to the House of War, described by Bernard Lewis.

However unrealistic this aim is—and it certainly is that—it is among the clearest examples of Islamist ideology put into supposed practice for a long period of time. That practice, while never eschewing outright the possibility of true, violent jihad, tends to be more political in nature, as demonstrated by former members like Maajid Nawaz, especially with most of HT’s activities in the Western countries where they continue to have a presence. The different branches of the organization seem to have different specific goals depending on the national demographics of Muslims living in the countries in which they operate—Denmark has a more significant Arab population, and England has a more significant South Asian population—so the rhetoric is tailored for those populations. However, the underlying ideology, tactics, and ultimate goal remain the same across the board. This mostly includes distribution of propaganda material, usually replete with the typical antisemitism that is in the blood of Islamism. According to Imran Khan on a 2003 broadcast of the BBC’s Newsnight, this was particularly evident with HT’s activities in Denmark. Khan described the material as follows:

In March and April 2002, Hizb Ut-Tahrir handed out leaflets in a square in Copenhagen, and at a mosque. The leaflet, which also appeared on the Danish group’s internet site, makes threats against Jews, using a quote from the Koran urging Muslims to “kill them wherever you find them, and turn them out from where they have been turned you out.” The leaflet also said, “The Jews are a people of slander...a treacherous people... they fabricate lies and twist words from their right context.” And the leaflet describes suicide bombings in Israel as “legitimate” acts of “Martyrdom.”

This is largely the extent of what HT does: they attempt to radicalize other Muslims into their worldview, while remaining essentially non-violent in their methodology (though shedding no tears when violence does occur). According to the United Kingdom’s Home Office in 2005, “[Hizb ut-Tahrir is a] radical, but to date non-violent Islamist group [that] holds anti-Jewish, anti-western and homophobic views.” This assessment only changed in 2024 with an attempt to get HT classified as a terrorist organization in the UK, which was largely in response to the group’s ramped up activities in the wake of the October 7th, 2023 pogrom in Israel.

However, it is in the United States where HT really shines as an example of Islamism’s velvet imperial approach. This is because, unlike the arched eyebrow and even hostility the group has received from various European governments (including an outright ban by the German government), HT enjoys the protections of the American Bill of Rights and, more importantly, something a bit closer to mainstream acceptance than its European counterparts. The result was the formation of Hizb ut-Tahrir America in the late 2000s under the leadership of for-profit Argosy University—Chicago professor, Dr. Mohammed Malkawi.

Many annual conferences were held (and often canceled) at various times in the following decade. The group’s spokesman Reza Iman claimed, “The call is not to bring that [an Islamic caliphate] here to this country or anything of that sort. The message is for Muslim countries to return to Islamic values.” This, according to the chairman of the Council of Islamic Organizations of Greater Chicago Zaher Sahloul, is simply untrue in the sense that, “They are very vocal and they target young Muslims in college who are attracted to their ideologies. They tend to disrupt lectures, Friday prayers. Most of the time they are kicked out from mosques.” However, their methodology is made very clear in this summary from Shiv Malik in his 2004 piece for The New Statesman:

In other words, Hizb [ut-Tahrir] doesn’t do elbow grease. It is no Hezbollah, with a large network of schools and hospitals. Nor does it condone suicide bombing. Its route to power is the peaceful coup, in which a general or politician seizes control of a state in the name of the caliphate. No arms would be used, because the Prophet Muhammad never raised arms to establish his state.

Malik also points out that “it seems laughable that Hizb, armed only with the righteousness of its ideas, could overpower some of the most ruthless regimes in the world.” However, while HT can reasonably be dismissed on the basis of widespread influence, especially in the eyes of the people to whom their fringe status matters most (that is, regular Muslims), fringe groups are always smaller than the ideology they spread and manage to normalize. And all sorts of radical ideologies have a way of flourishing when the societies in which they exist undergo their own tumult. This is why the kinds of things stated by HT and other Islamist groups started to be heard with more frequency after the atrocities of 10/7 and the beginning of the Israel-Hamas War.

While there is much more to say about the American left’s long tradition of being in the bag for Palestinian nationalism, HT and their ilk have many ways to make their cause seem more appealing to ignorant Western activists, especially when they begin to speak about the evils of capitalism and liberalism. One of HT’s pamphlets makes this clear, proclaiming that “[Islam] will prevail over all other ways of life including Western Capitalism and the culture of Western Liberalism.” It has become almost a given that these two forces—that is, liberalism and capitalism—have developed truly nefarious reputations in the eyes of many Western radicals. Islamist groups like HT are not unaware of this fact, and have enough operatives sophisticated enough to avoid talking about the more alienating aspects of their ideology, including their misogyny and homophobia (while also being careful to use terms like “Zionists” rather than “Jews,” at least when it matters).

…

This requires circling back to the original question of imperialism. How does this all come together? This softening of Islamism for the sake of Western audiences is not dissimilar to the French imperial approach of the 19th century in making their products—and thus national “brand”—so appealing. Because, like French wine- and silk-makers of centuries past, Islamists and the organizations and influencers following their ideological lead have been selling a lifestyle; an image. While creating a caliphate that enforces strict Islamic values is the long-term goal, creating a lifestyle via a supposedly moral framework is far more useful to Islamist groups. This is because, in selling this lifestyle, they have created a naïve rhetorical defense force in the West that will make it harder for Westerners to dismiss eighth century moral values out of hand for fear of being branded as xenophobic or racist. This lifestyle marketing approach is catalogued brilliantly by the polemicist Brendan O’Neill in his excellent After the Pogrom: 7 October, Israel, and the Crisis of Civilization, where he tackles what he calls the “cult of the kiffeyeh.” Pointing out that “kiffeyeh chic is all the rage” and, using a particularly telling example of a 3,000 pound version of the traditional scarf from Balenciaga, that “you can’t put a price on virtue signaling,” O’Neill is savage in his indictment, writing:

That an item of clothing has become so omnipresent among the virtuous set, that the activist class covets this scarf with such relish, that there has been an “influx of mass-produced kiffeyehs” into our societies [in the words of an article published in the Guardian], points to a performative streak in pro-Palestine activism. That it has become de rigueur in certain circles to flout all the laws of “cultural appropriation” and pull on this “hot accessory of the West” […] suggests the activist set is as keen to say something about itself and its own rectitude as it is about the predicament of the Palestinian people.

What is the activist set trying to say? To put it bluntly, it’s obviously a way to be fashionable and on the right side of history; a win-win scenario for many of the approval-seeking among us. As O’Neill writes:

And what is its usefulness? What holy service does this garment play in the lives of the elites? Its prime role is as a signifier of virtue. It is sartorial shorthand for ethical correctness. It communicates to your fellow travelers in the universe of luxury beliefs that you, too, have contempt for Israel and compassion for Palestine—an entirely requisite credo for access to the cultural establishment in the 21st century. Wearing the kiffeyeh in public, or posting photos of yourself wrapped up in one, is fundamentally a statement of your moral fitness for political high society. Far from being an act of solidarity, kiffeyeh-wearing is more about raising awareness of yourself, and your goodness, than it is about raising awareness of the Palestinians and their challenges.

All this is to say is that a lifestyle is being sold, and while it is being spread primarily by the forces of capitalism, the ideology that fuels the anger, which fuels the righteousness, and which thus fuels those forces of capitalism, is anything but capitalist. It is Islamist, and thus, an imperial force. Is this imperial force as powerful or as obvious and violent as the British lording over India, or the Belgians lording over Congo, or the Third Reich lording over Poland and parts of Yugoslavia? Of course not. Yet, as David Todd (and other scholars) have demonstrated (and as discussed earlier in this essay), empire need not be created or maintained at the point of a bayonet. It can indeed have a soft, velvet touch and has next to nothing to do with territorial acquisitions or resource extraction and more to do with sociocultural influence. This was shown by the French and their own conspicuous commodities and the lifestyle—the class—those commodities ultimately suggested. Todd writes about the phenomenon of of what he calls 19th century France’s “champagne capitalism,” which he defines as “the power base of a sophisticated model of global rayonnement [a positive influence due to prestige]” and, paired with occasional violence in certain corners of the world, something that created “what may be termed an empire of taste.”

It should be clear in the 21st century that a lifestyle is no longer just demonstrated by physical commodities or even mere physical appearance, but by the essence of the person’s beliefs and allegiances, often signaled through physical appearance, which can be done a few swipes across a touchscreen (a physical commodity in and of itself). The old forms of lifestyle commodification—the physical manifestations—are now unseemly, at best. There better be some kind of authenticity—maybe even humility—lurking underneath the surface there, and you better demonstrate that, otherwise you are no better than the stuffy, out-of-touch One Percent. As Brendan O’Neill summarizes in his polemic:

As [British political scientist] Matthew Goodwin explains, where the “old elite” derived its sense of social status from “physical manifestations of wealth, such as fine clothes, jewelry, foreign travel, servants, private carriages, and large properties,” the new elite tends to distinguish itself from the “low-status” masses by “focus[ing] far more on projecting their ‘cultural capital’ rather than their ‘economic capital’.” With prosperity “spread far more widely across society” than was the case in the past, “ostentatious displays of riches have much less significance.” Instead, says Goodwin, “for the sophisticated, financially secure, urban-dwelling, university-educated new elite,” a certain set of “fashionable beliefs has become the new signifier of social status.”

In other words, when one, say, makes the argument that Islamophobia is a devastating problem, but it is only made in response to criticism of Islam or even jihadism or Hamas (as is more common now), one is giving oneself one’s very own hyper-modern tres chic vibe, just with moral signaling rather than wealth signaling. It is a lifestyle, and one that only truly benefits two things: one’s own ego, and the ideologues who aimed to spread their beliefs in the first place. To bring this back around to imperial analysis, this can also be observed in the spread of 19th century France’s “empire of taste.” The most important takeaway was not that this velvet empire made the French rich; as David Todd writes, it “was not a purely capitalistic enterprise. It pursued profit, but also power and prestige.”

But is all this—Islamism, global capitalism, French luxury—really, truly a form of imperialism? Is this empire? To be fair, many would argue that it is not, both because “empire” is a pejorative term, as covered earlier, and because it has a specific meaning, and one that has been clearly defined throughout history. Todd does a wonderful job preemptively facing off these criticisms in his own work, noting that one can simply dismiss the usage of the word “empire” or “imperial” in the case of the French “empire of taste” as “a metaphor used to convey the crushing extent of French cultural domination,” or even a type of rhetoric used to “assuage wounded national pride after the loss of real, territorial empires in 1763 or 1815,” before he puts those concerns to rest. As Todd writes:

[It] is also very tempting to take the use of the word “empire” seriously, and highlight what was authentically imperial about French economic and cultural domination. Two imperial traits stand out. The first, given that all empires are collaborative yet hierarchical enterprises between different national or ethnic groups, is the contribution of numerous non-French auxiliaries to the dynamics of champagne capitalism; the second is the French state’s overtly political utilization of champagne capitalism’s successes […] in a bid to assert French supremacy in some parts of the world, or merely to proclaim France’s status as a global overlord.

If one was to remove any reference to France or its “champagne capitalism” in this passage and replace them with more neutral, general terms, it is pretty clear that a broader point can be made about imperialism that has little to do with territorial claims, resource extraction, or even economic enrichment. Those things could well be part of the picture, but what the French understood in the 19th century—and what Islamists understand in the 21st—is that influence can come in many forms, and the more amorphous and seemingly personal that influence is, the harder it is to extinguish. This was understood, as we saw at the beginning of this essay, by the United States’ intelligence agencies concerned with the spread of democratic, capitalistic values abroad to combat the spread of communist ones during the Cold War. If one wishes to go further back into the past, one need not look any further than the attempts to spread Christianity around the world. With the faith sporting over two billion adherents and showing no sign of slowing down, one could argue that the velvet empire of Christianity is the greatest success story for soft imperial power in human history.

To make the point while at risk of sounding pedantic, what even is imperialism? What is it really? It certainly involves the things mentioned a moment ago—territory, resources, enrichment. And it certainly has both hard and soft methodologies. But in the end, it is about power; about influence. Not power for its own sake, but the power of the ideas and values held by those who wish to spread those ideas and values in the places where they matter. That, in turn, will bring about all of the territory, resources, and enrichment one could envision. There are those who crave those things and believe—sometimes for good reason, thanks to their own strength—that they can be obtained through rudimentary, crude physical domination—the brutes, we can call them. The difference between them and the champions of soft power—from the French in the 19th century, the Americans in the 20th, to the Islamists in the 21st—is that the brutes of the world have so little imagination.

It is worth noting that Orwell’s own classic Animal Farm was sponsored and promoted by the British Foreign Office’s anti-communist unit known as the Information Research Department, and, according to historian Hugh Wilford (my professor in American imperialism, as it happens), they “had already exploited the Cold War propaganda potential of Orwell’s fable, sponsoring the publication of several foreign-language translations and even producing a cartoon-strip version for dissemination in South America, Asia, and the Middle East (one official noted the happy coincidence that ‘both pigs and dogs are unclean animals to Muslims’).” This does nothing to diminish Orwell’s scathing indictment of Stalinism or to pretend it wasn’t effective at spreading its intended message; only that the British government recognized its power and gave it a little boost where it counted. As we will see (or have seen), cultural imperialism is arguably endemic in the modern globalized world, and therefore it is appropriate to make qualitative judgments about what is being imported and exported, as far as ideas go. If it is not obvious, I personally think Orwellian (in the good sense of the word) anti-totalitarian leftism is a good thing to spread, if we are to make qualitative judgments; and I think we should.

Calling it a “bogeyman,” while certainly dismissive, is not to say Christian nationalism does not exist, but rather to say that it does not appear as strongly or meaningfully as examples of Islamism tend to do.

One may wish to make a counterargument that there are Zionist/pro-Israel organizations that do and have done the same, especially with evangelical Christians and politicians who align with them. That is indeed true. That is also not what this essay is about.

Thank you for your latest newsletter. I just wanted to say that I have been listening to some of the podcasts from 2022. Somehow, I must have downloaded them when traveling and the ads are all in German. It's both odd and interesting to be in the middle of a podcast about Nazi Germany and an ad for Berlin car sharing apps or German Shopify pops up!

Anyway, keep up the good work.

Your last sentence seems contradictory to me. How do you separate importation of ideology from importation of the people who transport that ideology? Is the issue failure to hold recent immigrants to the same norms of behavior as established residents?