This is another adaptation of research I have conducted during my time in graduate school. This time, I’m going to subject all of you to the “delights” of historiography, that is, the history of history. I joke because while historiography is not my favorite thing to do—I prefer pure research—I do think this was an interesting topic that I studied and I think at least some of you will find it interesting too, especially those of you who enjoyed my previous essay written in the midst of the Great Los Angeles Fires of 2025 (can I make that name stick?).

It’s also something I’ve spoken about a number of times on History Impossible—that is, the role of infectious disease on events throughout history. This being a historiography, it takes a much more zoomed out view on that role and, you’ll might be surprised to learn, there hasn’t been as much literature on the subject as there should be. It has added to my suspicion that while there are plenty of people interested in the subject of infectious disease at particular historical crossroads (or causing them), there does seem to be an avoidance of the subject. Perhaps it’s natural—the idea of certain things being out of humanity’s control that we may otherwise see as being within our control is scary. But perhaps it just feels bad to think about illness, especially for those of us who have lost loved ones to it. But there is agency to be found and many scholars have recognized that; that’s what this essay looks at.

Anyway, please enjoy this attempt from yours truly at making sense of this strange field we call history.

…

When the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 hit, humanity's past relationship with infectious disease became of greater interest. There is no shortage of diseases that have occurred in the past and caused equal if not far more profound disruptions to the human experience than COVID-19. It forced us to consider how significantly transformative historical events might have been impacted by the presence of infectious diseases, and how that might allow us to reframe their significance in a different context. However, despite the renewed interest after 2020, previous scholarship had been exploring the role of infectious disease in shaping significant human-driven historical events for decades. It had frequently faced controversy thanks largely to its supposedly deterministic nature that robbed human beings of agency. This concern over agency became particularly acute in conversations about infectious disease's role in moments of significant historical changes like conflict, conquest, and colonization, which had for many years been ascribed with total or near-total human agency. This concern was understandable, with many pioneers in this field of environmental history edging closer to various levels of determinism in their analyses, but from 1970s onward, there was a constant conversation occurring within the field, and a more nuanced view began to take shape.

With the publication of J.R. McNeill's Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914 in 2010, it became apparent that this more nuanced view of infectious disease's role in human history started to come into greater focus. It had taken many years to get there, and it had not been without controversy and a fair amount of interdisciplinary soul-searching on the part of the scholars who wanted to take on this task of re-contextualizing the human experience's most dramatic historical events. This re-contextualization casts the supposedly human-driven events of conflict, conquest, and colonization in a new light, in which a greater, deeper understanding of just how much agency human beings actually have—neither total nor limited—can be appreciated by the historian.

Within some circles, the first half of the 20th century had seen some discussion of the role infectious disease had played in human history, but it had been relatively limited. The biologist Hans Zinsser had written a book called Rats, Lice, and History in 1935 to some moderate success, and in 1941, a junior statistician named Clara E. Councell had written a paper for Public Health Reports in which she had stated that “The waging of war has always been attended by increases in the prevalence of disease,” but noted that “Only a blurred picture can be obtained of the true character and incidence of the great waves of fatal illness that decimated the nations involved in early wars.”1 This limited appreciation was fully articulated in 1949 when “the godfather of modern environmentalism,” Aldo Leopold, “called for a rewriting of history from an ecological perspective.”2 However, a true shift in this direction would not begin to appear until the early 1970s. During this time, an increasing number of scholars began to take the role of disease far more seriously as a significant contributing factor in events otherwise thought to primarily be the result of human whim.

Thanks to its downstream effects, the so-called “discovery” of North America offered fertile ground for questions of human agency at the hands of environmental forces like disease. This was at the center of Alfred W. Crosby's The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492 (1972), in which Crosby demonstrates that “the fatal diseases of the Old World killed more effectively in the New.”3 This re-contextualization of one of the modern world's most significant changes was profoundly significant because it challenged the fundamental assumptions most historians had about the arrival of Europeans on the American continents. Crosby notes the fundamental contradiction at the heart of Native American resistance and the fact that they still were unable to stop the tide of European conquest and seeks to explain why this was the case. Previous scholarship that highlighted technological and cultural superiority of the Europeans would not suffice, especially when it neglected the role infectious disease actually played, as evidenced by written accounts from indigenous survivors in the years after European contact.4

Crosby sought to correct the record by exploring the role of biological exchange, which included narratives of disease exchange, and how that led to shifts that changed the landscape of the New World. This included an examination of the botanical and zoological imports from the Old World and how they impacted the peoples already living in the Americas. Because animals are one of the largest vectors for disease exposure, the introduction of several species into the new environment brought with them several of the diseases that wrought havoc on indigenous Americans, like measles. However, if one counts the arrival of new humans as a zoological import—and Crosby would think we should—then that helps explain the introduction of human-exclusive disease into the American ecosystem, like smallpox. These introductions and interactions created massive effects on the indigenous populations that went well beyond just killing them off in droves. As Crosby explains, “One can only imagine the psychological impact” of the epidemics felt by indigenous people, which “must have shaken the confidence of the Incans that they still enjoyed the esteem of their gods.”5

Crosby's ability to reasonably infer the cultural significance of infectious disease upon a people who had once seen few equals helps demonstrate the previously less-appreciated downstream effects of infectious disease in the conquest of the New World. Crosby made some assertions in The Columbian Exchange that would turn out to be challenged by later scholarship, such as the claim that syphilis was likely introduced to Europe by indigenous Americans.6 However, Crosby's inquiries were central in starting the conversation about what determined the outcomes of European contact. This, in turn, opened the field to broader questions about the role played by infectious disease on significant historical events.

…

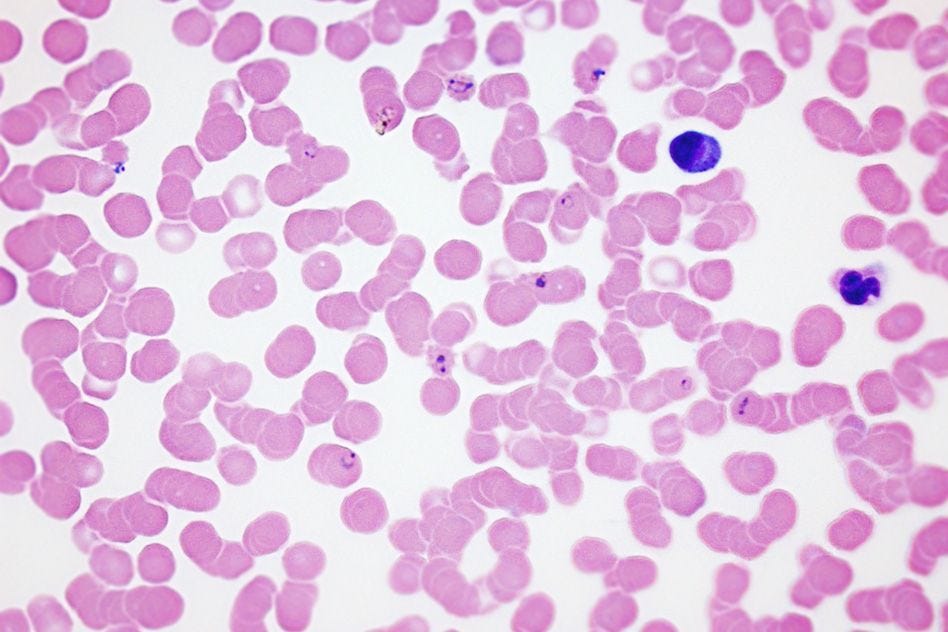

Supplementing Crosby's work in 1972 was medical historian Frederick F. Cartwright and historian Michael D. Biddiss' Disease and History, which offered a broader view than Crosby of the various diseases that have affected mankind across time and helped universalize the idea that infectious disease played a significant role in human history's most dramatic moments. Cartwright and Biddiss made a noteworthy contribution with their work by demonstrating infectious disease's “effect not only upon historically important individuals, but also upon the peoples,” ranging from diseases of the ancient world to more modern maladies.7 For example, they point to the spread of malaria into Rome's surrounding agricultural districts in the 1st century B.C.E. as being “probably more catastrophic than the attacks of Goths and Vandals,” since the effects of such an outbreak “accounted for the slackness of spirit which characterized the later years of Rome.”8 They also followed the same chain of cultural logic used by Crosby and suggest that had it not been for the centuries of plague that convulsed Rome after the death of Christ, the people of the Roman world would not have been so susceptible to the rhetoric and world vision of early Christianity.9

This could well be overstated, but we see the beginning of a more environmental—and arguably deterministic—view of human history forming. Indeed, this can be seen when Cartwright and Biddiss highlight the Black Death of the 14th century as “a world-wide pandemic,” after which they make the argument that “the devastation wrought in Scandinavia may ultimately have had a greater effect upon world history than did the English catastrophe [of the Black Death].”10 One can sense a bit of the traditional historiography slipping into their analyses, with frequent invocations of “Great Men,” including the Borgias, Ivan IV, and Henry VIII, in their exploration of the effect syphilis had on the course of history. While it is certainly significant that they would approach the behavior of well-known rulers and historical figures from this standpoint as opposed to a moral one, this suggests that some old habits die hard. It would be another four years before the insights explored by the likes of Crosby, Cartwright, and Biddiss would be given new life within the field.

William McNeill's Plagues and Peoples (1976) helped break new ground with its more nuanced approach than the previous scholarship. It did so by attempting to further provide “a fuller comprehension of humanity's ever-changing place in the balance of nature,” by providing a broad analysis of humanity's interaction with disease, including conflict, conquest, and colonization.11 Starting his chronology with the beginning of humankind itself, McNeill was the first to place human beings in a truly environmental context, showing how we, like all animals, are part of a constantly shifting ecosystem. He notes that despite our incredible ability to adapt to rapidly changing circumstances, our species' “relations with microparasites remained until the nineteenth century largely biological, that is, beyond or beneath human capacity for conscious control.”12 This re-contextualization went well beyond historical events and instead focused on humankind as a biological species, which helped make the ultimate case for which environmental historians had been advocating: that human beings are not exempt from environmentally-driven forces.

Despite his significant re-contextualization of humanity as a species, McNeill follows the trend that had been set by Cartwright and Biddiss by moving through the rest of human history, from the ancient world until the modern day and exploring how disease made impacts along the way. Like Cartwright and Biddiss, he also uses cultural responses to disease to help explain the rise of certain religious views, including Christianity. Noting that for Christians believed that “care of the sick, even in time of pestilence, was for them a recognized religious duty,” McNeill argues that Christianity thus had an advantage over the old pagan religions of Europe that did not share such views, at least in terms of incentivizing conversions.13 He cites early Christian writers such as Cyprian in making this case, though unlike Cartwright and Biddiss, he outright admits that this speculation, however compelling, cannot be proven.14

McNeill does not always follow his own advice throughout the rest of the monograph, but what this shows is a growing awareness of the limitations of unchecked environmental views of history, especially when they begin to veer too close to cultural determinism. After all, who is to say what singular natural force “caused” a cultural shift more in favor of Christianity, especially in such monocausal terms? Whether he was aware of it or not, McNeill was starting a trend in greater intellectual humility when he hedged his observations in this way. While some future writers of environmental history would not heed this advice, it represents the moment that a shift in the historiography began to occur.

While less apparent than it was in the 1970s or the 1990s, there remained some historical interest in the role played disease in human history during the 1980s, which saw the growth of an appreciation for a more ecological, rather than purely environmental approach to history, which included the study of the effects of infectious disease. Most apparent in this trend was William Cronon's famous 1983 monograph, Changes in the Land (1983), which had influence matched by very few other historians. As J.R. McNeill puts it, Changes in the Land “enjoyed great success and inspired unabashed imitation.”15 Making use of primary source documents like diaries, letters, and other period accounts, as well as archaeological records, Cronon takes a broader approach similar to Crosby's when looking at the eponymous changes in the North American landscape, but he spends some significant energy exploring the role of infectious disease in working to the European colonists' advantage. As he refers to it, it was “the single most dramatic ecological change in Indian lives, one who full significance historians have only recently come to understand.”16

By describing the lack of natural defenses against Eurasian and African diseases as simultaneous blessing and curse, Cronon broke ground by detailing the human cost of Old World diseases upon the people of the New, noting astonishing village mortality rates of up to 95 percent, as well as documenting the social cost of epidemics that brought low more than just tribal leaders, including the effect on powwows and Christianizing effect on some populations.17 This again makes sure to de-emphasize the role of “Great Men” in history in order to emphasize the role of environmental forces. But Cronon pushed the field forward in one very important way: by noting how the interaction between indigenous Americans and European colonists—including the introduction of infectious disease—created different relationships between human being and land, thus demonstrating a novel causal chain that had not yet been fully appreciated.

As Cronon notes at the very end of his work, “colonists and Indians together began a dynamic and unstable process of ecological change,” suggesting as much.18 This notion of an ecologically-driven causal chain was noteworthy for highlighting the relationship implied by the term “ecological”—symbiotic, parasitic, or otherwise—which in turn provided a future foothold for scholars and critics of environmental history that were concerned with the question of agency. By emphasizing the ecological role of infectious disease in conflict, conquest, and colonization, Cronon was laying a more interdisciplinary groundwork for a further development in the scholarship.

…

It was not until the 1990s that the question of whether or not disease was a significant causal driver for historical events like conflict, conquest, and colonization began to take a clearer shape. It was during this time that we saw a rise in non-historians contributing to the conversation, including the geographically-focused Guns, Germs, and Steel (1997) by the physiologist-by-training Jared Diamond. Diamond's core argument—that the answer to the question of “why history unfolded differently on different continents” lays in expanding the scientific frontiers of the study of history—was provocative for the time and remains so to this very day.19 This was for many reasons, not least of which was Diamond's status as a non-historian combined with his work winning the esteemed Pulitzer Prize.

However, it was also because Diamond considered his work part of the environmental history canon, something with which many environmental historians did not and do not agree. This includes J.R. McNeill, who wrote in 2010 that the work “aroused sharp criticisms for its efforts to explain the long-term distribution of wealth and power around the world in environmental terms.”20 It is understandable that this pushback would occur not just because Diamond is not a historian, but because his argument that geographical distribution lie at the core of civilizations' “success” and “failure” struck many historians as fundamentally deterministic. However, because Diamond's analysis allowed for a significant role of infectious disease in this sweeping narrative of civilizations' rise and fall and was so culturally resonant to the point of becoming a household name, it is without question that his place in the historiography is deserved.

While discussing the broader implications of Eurasian germ exposure reaching beyond the “collision of the Old and the New Worlds,” into the worlds of “the Pacific islanders, Aboriginal Australians, and the Khosian peoples […] of southern Africa.”21 With this, Diamond is calling to mind the same kind of all-encompassing arguments made by the likes of William McNeill two decades earlier, but he is more forthrightly answering the oftentimes silent question that makes many historians shift in their shoes: why do some societies fail and some succeed? Diamond does not stoop as previous generations of historians and scholars did by invoking arguments that suggested inherent cultural (or, in darker cases, biological) superiority of some peoples over others. Rather, he acknowledges from the outset that “the so-called blessings of civilization are mixed,” and that “History followed different courses for different peoples because of differences among peoples' environments, not because of biological differences among peoples themselves.”22 This, combined with his desire to see history become more scientific, demonstrates both a preemptive awareness of many criticisms that would be directed at Diamond's book, and a desire to see his work expanded upon in the years to come. And his contribution, however controversial in the eyes of trained historians, did indeed serve as a catalyst for further study of infectious disease in the field of environmental history.

In 1998, Diamond was joined by several other writers, some historians and others not, demonstrating both the influence of Diamond's arguments and the need to approach the history of infectious disease in ways apart from a strictly historical perspective. The virologist Dr. Michael Oldstone was one of these non-historians with his 1998 monograph, Viruses, Plagues, and History, which sought to describe “the politics and the superstitions evoked by viruses and the diseases they cause.”23 Oldstone uses his background to explain the principles of virology and immunology, setting the groundwork for the rest of the monograph, in which he discusses what he calls the “success stories” of smallpox, yellow fever, measles, and polio.24

This places Oldstone’s work in a unique context where his expertise in medicine prompts him to look at infectious disease as something to be solved, even with its attendant power over the course of human events. For example, Oldstone makes it clear that “smallpox played a crucial role in the Spanish conquest of Mexico and Peru, the Portuguese colonization of Brazil, the settlement of North America by the English and French, as well as the settlements of Australia.”25 And while he explores the downstream effects of smallpox, including the incentive it created to import more African slaves for labor, he also spends considerable time exploring the progress made toward vaccination and eradication of the disease.26 In this way, Oldstone's approach casts human agency in a brighter light than previous scholarship on the subject and is something that would start to make a greater appearance in the years to come.

That same year also included the works from more traditional historians like medievalist John Aberth's The First Horseman: Disease in Human History (1998) and Philip D. Curtin's Disease and Empire: The Health of European Troops in the Conquest of Africa (1998). Aberth's book takes a broader approach by building on his previous work that solely focused on medieval Europe and expanding it to include the epidemics of European diseases in the Americas, the spread of plague in India and China during the 19th century, and the modern spread of HIV/AIDS in Africa after 1982. This mirrors the global approach that made its appearance from the very beginning of the historiography, but where Aberth diverged from the likes of William McNeill was his interest in the policies that were put forth by authorities. For example, in his middle section exploring the outbreaks of bubonic and pneumonic plague in India during the reign of the British Raj in the late 19th century, Aberth looks at “the most concerted effort ever undertaken to date in order to combat a disease,” with the passage of the Epidemic Diseases Act in 1897.

This colonial policy was not just altruistic, Aberth notes, but also more “self-serving” in the sense that “the preservation of its lucrative trade within and without India was a high priority for the government.”27 This interest in imperial policy from Aberth makes it clear that the view being adopted by historians of infectious disease was taking on the same ecological tint that had been pioneered by the likes of William Cronon during the previous fifteen years. The word “ecology,” in this case, implies more than just the natural world; it indeed implies a relationship, and in the historical context, the relationship between human decision-making and environmental pressure is the ecosystem at work. Aberth is among the first historians to make this point explicit. The relationship between policy and infectious disease—only hinted at from the likes of Michael Oldstone—places human agency in a more nuanced light. Instead of simply looking at disease the way a physician or a scientist would, Aberth makes it clear that it is a driving force and something with which humans interact.

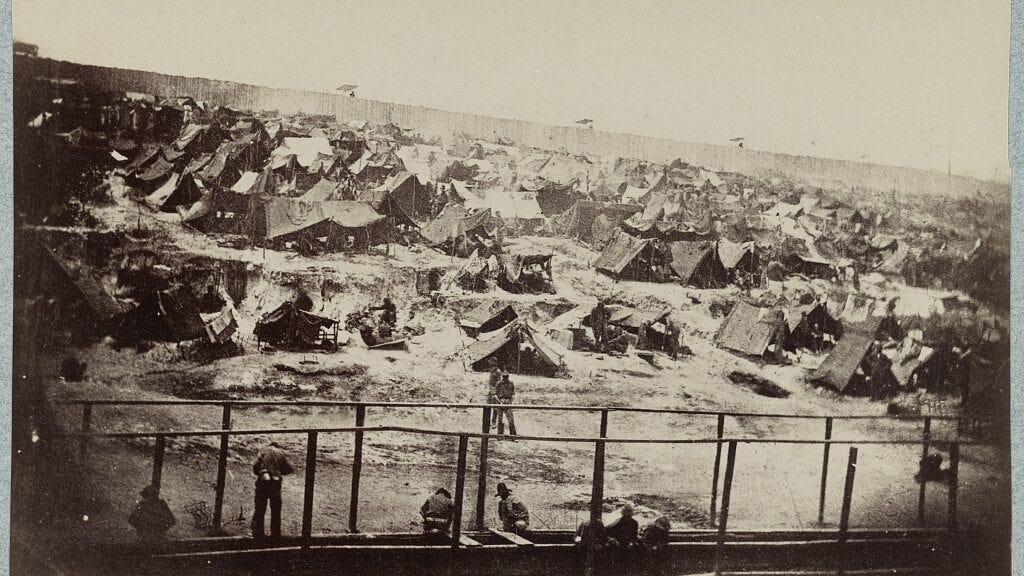

Conversely, yet similarly, Philip D. Curtin uses his expertise in African history to explore the role disease and its treatment played during the relatively brief window of 1815-1914 during which European troops grappled with infectious disease while attempting to conquer Africa. This was novel in that it narrowed the focus of scholarship on the role of infectious disease to specifically question its role in the idea, creation, and maintenance of empire during the 19th century. While Aberth placed focus on imperial policy as it related to infectious disease in some instances of his work, Curtin made it his monograph's entire focus. Compiling data of mortality rates from different periods of conquest and conflict and the reactions experienced by citizens of the home country, Curtin is able to demonstrate that attitudes on disease were strongly correlated with attitudes of imperial conquest. For example, while death rates due to disease were shockingly high at times—sometimes as high as 25%—“the public was apparently unconcerned as long as the actual number seemed small and the national gain seemed large.”28

By linking public attitudes toward imperial conquest and disease-related death rates, Curtin is engaging in an ecological argument in which the ideas at the core of imperial conquest could override what might be seen as a typical appreciation of public health. Curtin also explores the role of imperial competition in Africa in the last decade of the 19th century and how infectious disease played a role in affecting that competition. While malaria infections drove back French forces in Madagascar, the British used their knowledge gained over the years in dealing with tropical diseases to secure a victory in Sudan and, more importantly, “a major victory over a European rival,” thus placing imperial conquest and competition in a disease-based context.29 This, like Aberth's re-contextualization, shows the further development of the field toward a broader-scale, ecological approach to explaining the role infectious disease has played in the most significant events of modern history, and paving way for the scholarship that was to come in the next decade.

…

In the 2000s, the scholarship on disease's role in historical events grew ever-more diverse, with many non-historians continuing to discuss the role disease played in human history, sometimes in the context of public health, other times in the context of national security. However, historians M.R. Smallman-Raynor and A.D. Cliff sought to examine the role disease played in the history of modern conflict. In their work, War Epidemics: An Historical Geography of Infectious Diseases in Military Conflict and Civil Strife, 1850-2000 (2004), they demonstrate that “the link between war and disease remains as strong as ever.”30 They, like Philip Curtin before them, restrain their time scale to the modern era, but like Michael Oldstone bring it up to what was for them present day. They first provide a general overview of infectious disease's relationship to war and conflict throughout history, and then transition to trends across space (that is, regional) and time.

Smallman-Raynor’ and Cliff’s granular, data-driven approach demonstrates that death rates during war, even in the modern era (which we often associate with scientific progress), were vastly inflated by the role played by infectious disease; as they write, “infectious diseases were the most significant causes of mortality in the nineteenth century.”31 However, they take a different approach than one might expect, pointing to the fact that it is war that increases the casualties caused by disease, not the other way around. In pointing to the fact that disease spreads among the civilian population thanks to the effects of war—such as mass population displacement combined with the lowering of hygienic standards—they demonstrate that disease is part of the relationship—the ecology, if you will—of human conflict. Smallman-Raynor' and Cliff's approach came closer to Jared Diamond's sweeping vision to applying scientific rigor to the study of history, but six years later, the relationship between disease and supposedly human-driven events would be distilled into a more singular essence.

In 2010, J.R. McNeill, son of William McNeill, released Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914, which persuasively answers the question of disease's role in the shaping of New World's formative conflicts and revolutions. McNeill's contribution to the scholarship is to fully foreground the relationship between disease and human behavior and, thus, historical consequences; as he writes, “viruses made history […] but they did so only because soldiers and statesmen, slaves and revolutionaries acted in certain specific ways.”32 McNeill examines what is frequently cited as the most significant change in modern history—that is, the conquest and colonization of the New World—and examines how infectious disease played a role in the outcomes of this conquest and colonization, as well as the conflicts that followed. He does not discount agency, but he also explains that “outbreaks were not random except in their timing,” and “formed a regular pattern that constrained randomness, and severely narrowed the range of likely outcomes of the political struggles in the Greater Caribbean.”33

Taking a page from William Cronon by focusing on the land itself, McNeill also shows that the environment itself was ideal for the flourishing of the disease-carrying mosquitoes, because “no native American mosquito occupied A. aegypti's favored niche,” leaving it free from competition, and that the Caribbean's rainy season and subsequent humidity “normally brought a surge in mosquito populations.”34 This demonstrates that while human agency may have been behind the introduction of such invasive species with virulent diseases, the environment didn't even need human activity to let these species and diseases to thrive and spread (though it certainly helped). In addition, by finding an environment perfectly suited for the spread of infectious disease, the early colonists also secured their domination and ability to resist rival imperial forces.

As McNeill shows, the presence of disease also helped determine the outcomes of military campaigns, primarily between the British and the Spanish in the mid-18th century and thus the outcome of imperial dominance in the region for years to come. The fact that infectious was responsible for such staggering losses at Cartagena by the British—8,000 dead total, with one regiment suffering 85% losses—is very significant when “the black vomit left the Spanish untouched,” thanks largely to the differential immunity the defending Spanish had developed over the years that the British didn't have.35 By centering differential immunity in this way, McNeill helps us see the importance of forces well beyond the locus on human control, but also shows how human agency was able to flourish. Had it not been for the differential immunity itself and the Spanish knowledge of it, the outcomes of many of the Caribbean's conflicts in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries might have been very different, producing vastly different outcomes over time. That potential alone is what demonstrates the significance of the complex ecological relationship at work between human behavior and environmental pressure.

The continuity of historical scholarship from Crosby's The Columbian Exchange in 1972 to J.R. McNeill's Mosquito Empires in 2010 suggests that our interest in infectious disease playing a role in affecting the outcomes of significant past events is still developing. The movement from a more general view of environmental effects determining outcomes to a more ecological view of environmental pressures interacting with human agency has opened the door to future scholarship. This scholarship can take a more nuanced view, both on the effects of infectious diseases on event-shaping behavior, and on how the outcomes of significant events like conflict, conquest, and colonization may require some re-contextualization. The continued embrace of a multidisciplinary approach may also yield rewards, such as incorporating psychology or sociology into the study of infectious disease's effects. This could do the same for, say, political history, as it has done for military history or the history of colonization or revolution. We can recognize the importance of agency while also acknowledging that, as these four decades of scholarship have shown us, that agency only takes us so far. Striking this balance has not been easy and it will continue to create challenges with future scholarship, but the potential for a deeper understanding of human agency and environmental pressures in history is immense.

Bibliography:

Aberth, John. The First Horseman: Disease in Human History. London: Pearson Publishing, 1998.

Cartwright, Frederick F. and Biddiss, Michael. Disease and History. Stroud, United Kingdom: Sutton Publishing, 1972.

Councell, Clara E. “War and Infectious Disease.” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 56, no. 12 (1941): 547-573, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4583663.

Cronon, William. Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. New York: Hill and Wang, 1983.

Crosby, Alfred. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1972.

Curtin, Philip D. “Disease Exchange Across the Tropical Atlantic.” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 15, no. 3 (1993): 329-356, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23331729.

Curtin, Philip D. Disease and Empire: The Health of European Troops in the Conquest of Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997.

McNeill, William. Plagues and Peoples. New York: Doubleday, 1976.

McNeill, J.R. Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

McNeill, J.R. "The State of the Field of Environmental History." Annual Review of Environment and Resources 35 (2010): 345-374, https://doi.10.1146/annurev-environ-040609-105431.

Oldstone, Michael B.A. Viruses, Plagues, and History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Patterson, James T. “How Do We Write the History of Disease?” in Health and History 1, no. 1 (1998): 5-29, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40111315.

Smallman-Raynor, M.R. and Cliff, A.D. War Epidemics: An Historical Geography of Infectious Diseases in Military Conflict and Civil Strife, 1850-2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

FOOTNOTES:

1 Clara E. Councell, “War and Infectious Disease,” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 56, no. 12 (1941), 547-548, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4583663.

2 J.R. McNeill, “Foreword to the 30th Anniversary Edition,” in The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences to 1492, by Alfred W. Crosby (CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1972), vii.

3 Alfred Crosby, The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1972), 37.

4 Ibid., 36.

5 Ibid., 54.

6 Ibid., 139-140.

7 Frederick F. Cartwright and Michael D. Biddiss, Disease and History (Stroud, United Kingdom: Sutton Publishing, 1972), 2.

8 Ibid., 11.

9 Ibid., 19.

10 Ibid., 32.

11 William McNeill, Plagues and Peoples (New York: Doubleday, 1976), 5.

12 Ibid., 28.

13 Ibid., 108.

14 Ibid., 109.

15 J.R. McNeill, “The State of the Field of Environmental History,” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 35 (2010), 349, https://doi.10.1146/annurev-environ-040609-10543.

16 William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983), 85.

17 Ibid., 85-89.

18 Ibid., 170.

19 Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997), 9.

20 McNeill, “The State of the Field of Environmental History,” 360.

21 Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel, 213.

22 Ibid., 18, 25.

23 Michael B.A. Oldstone, Viruses, Plagues, and History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 9.

24 Ibid., 51.

25 Ibid., 59-60.

26 Ibid., 72-84.

27 John Aberth, The First Horseman: Disease in Human History (London: Pearson Publishing, 1998), 77.

28 Philip D. Curtin, Disease and Empire: The Health of European Troops in the Conquest of Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 92.

29 Ibid., 194-201.

30 M.R. Smallman-Raynor and A.D. Cliff, War Epidemics: An Historical Geography of Infectious Diseases in Military Conflict and Civil Strife, 1850-2000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 729.

31 Ibid., 174.

32 J.R. McNeill, Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 6.

33 Ibid., 304.

34 Ibid., 40, 41.

35 Ibid., 162, 163.

Check out Edwards and Kelton, "Germs, Genocide, and America's Indigenous Peoples," in the JAH, as well as Inescapable Ecologies by Linda Nash