Mother's Wrath, Mankind's Bargain

Nature does not care about fault, but people always will

“The palaces of crowned kings—the huts,

The habitations of all things which dwell,

Were burnt for beacons; cities were consum'd,

And men were gather'd round their blazing homes

To look once more into each other's face;

Happy were those who dwelt within the eye

Of the volcanos, and their mountain-torch:

A fearful hope was all the world contain'd;

Forests were set on fire—but hour by hour

They fell and faded—and the crackling trunks

Extinguish'd with a crash—and all was black.”

—Lord Byron, “Darkness”

“And I thought: The world is our relentless adversary, rarely outwitted, never tiring.”

—Jim Shepard, Battling Against Castro

“Who could have predicted that the bill would arrive with a sudden shift of wind in the middle of a mild January morning? A thousand storms of dust and ice and poverty and despair have come and gone since then, but this is the one they remember. After that day, the sky never looked the same.”

—David Laskin, The Children’s Blizzard

…

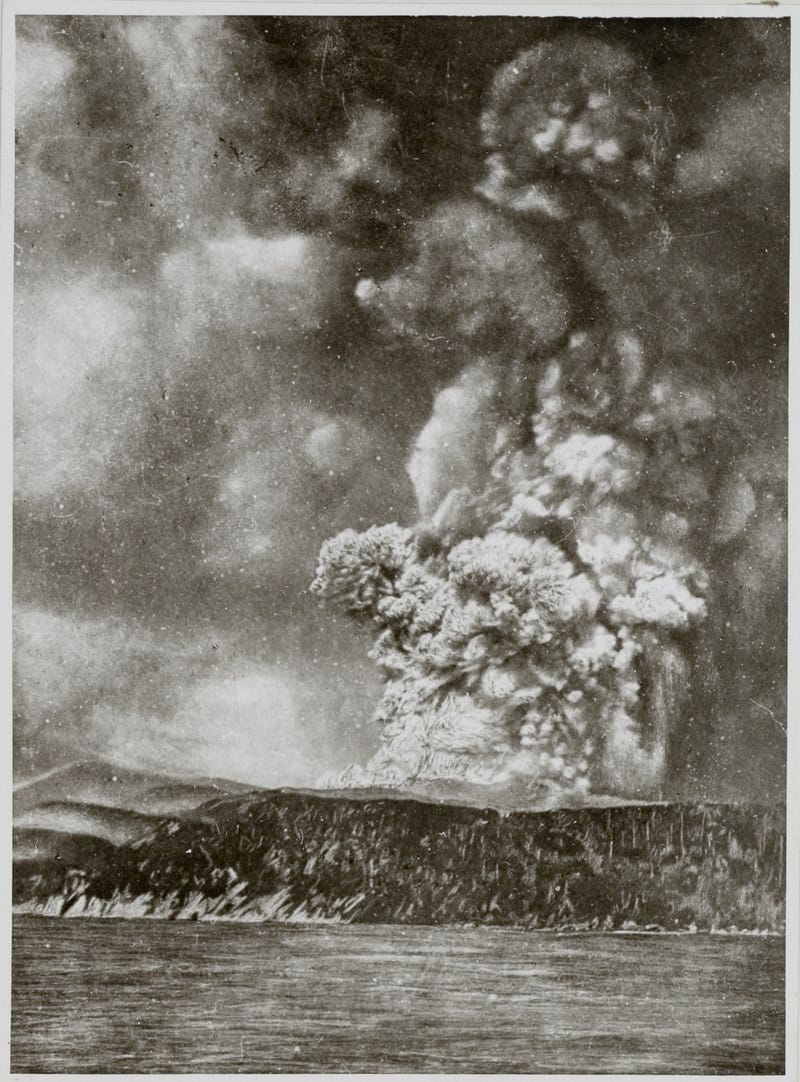

On the morning of May 20th, 1883, the captain of the German corvette Elisabeth, a man named Hollmann began to understand why so many tremors were being felt in this region of the Pacific Ocean. The Elisabeth was on its way home to after a two-year stint doing picket duty around the Chinese city of Tsingtao, and was rounding the Indonesian archipelago near the islands of Java and Sumatra. That morning, the source of the tremors became clear to everyone looking at the island seventeen nautical miles away from the Elisabeth. Captain Hollmann would record what he saw as follows:

[Without warning] we saw from the island a white cumulus cloud, rising fast. It rose almost vertically until, after about half an hour, it had reached a height of almost 11,000 meters. Here it started to spread like an umbrella, probably because of it had reached the height of the anti-trade winds, so that soon only a small part of blue sky was seen on the horizon. When at 4 o’clock in the afternoon a light south by southeast breeze started, it brought a fine ash dust which increased strongly […] until the entire ship was covered in all parts with a uniform fine gray dust layer.

The chaplain of the Elisabeth would also describe the massive ash cloud that blocked out the light of the near-full moon that night and noted that the next morning, the deck of the Elisabeth “looked like a mill ship, or more precisely, like a floating cement factory” thanks to the “gray sticky dust” covering everything. Describing the sky, the chaplain wrote that it “appeared like a large bell made of rather dull milky glass in which the sun hung like a light blue lamp.” And this was only the beginning. This event was as much of a warning for what was to come as anyone was going to get. Three months later, the mountain from which the ash that blanketed the Elisabeth exploded with an estimated force of 200 megatons. For context, the largest nuclear bomb ever detonated—the Soviet Union’s AN602, or “Tsar Bomba”—was 50 megatons.

The Krakatoa eruption did not occur all at once; in fact, some of the most visually dramatic aspects of the mighty explosion occurred the night before its final culmination on the morning of August 27th. These aspects were recorded by several ship captains in the vicinity and make for shocking reading. As an example, a one Captain Watson was interviewed by The Atlantic Monthly the following year, and recalled hearing “a strange sound as of a mighty crackling fire, or the discharge of heavy artillery at one or two seconds’ interval,” after which “darkness spread over the sky, and a hail of pumice stone fell on us, of which many pieces were of a considerable size and quite warm.” The entire night, Watson recalled, “was a fearful one; the blinding fall of sand and stones, the intense blackness above and around us, broken only by the incessant glare of varied kinds of lightning, and the continued explosive roars of Krakatoa made our situation a truly awful one.” When the volcano finally appeared through the blackness at around 11pm, Watson remembered seeing “chains of fire appear[ing] to ascend and descend between [the island] and the sky, while on the southwest end there seemed to be a continued roll of balls of white fire.” The explosions continued all through the night, culminating in four increasingly huge and devastating ones the next morning, with the final one setting off at 10:02 AM, accompanied by massive tsunamis and pyroclastic flows (that is, extremely hot mixtures of rock, ash, and gas), swallowing up towns and villages on the surrounding islands. One of these towns was Ketimbang, in which a Dutch colonial family called the Beyerincks were living. Mrs. Beyerinck would provide a harrowing account of their ordeal as follows:

Suddenly, it became pitch dark. The last thing I saw was the ash being pushed up through the cracks in the floorboards, like a fountain. I turned to my husband and heard him say in despair, “Where is the knife? I will cut all our wrists and then we shall be released from our suffering sooner.” The knife could not be found. I felt a heavy pressure, throwing me to the ground. Then it seemed as if all the air was being sucked away and I could not breathe. I felt people rolling over me. No sound came from my husband or children. I remember thinking, I want to go outside, but I could not straighten my back. I tottered, doubled up, to the door. I forced myself through the opening. I tripped and fell. I realized the ash was hot and I tried to protect my face with my hands. The hot bite of the pumice pricked like needles. Without thinking, I walked hopefully forward. Had I been in my right mind, I would have understood what a dangerous thing it was to plunge into the hellish darkness. I ran up against branches and did not even think of avoiding them. I entangled myself more and more. My hair got caught up. I noticed for the first time that [my] skin was hanging off everywhere, thick and moist from the ash stuck to it. Thinking it must be dirty, I wanted to pull bits of skin off, but that was still more painful. I did not know I had been burnt.

In the end, Krakatoa claimed the lives of 36,417 people, injuring thousands more, and wiped out 165 villages and towns. As geologist and historian Simon Winchester writes, “almost all of them, villages and inhabitants, were victims not of the eruption directly but of the immense sea-waves that were propelled outward from the volcano by that last night of detonations.” Injuries like those of Mrs. Beyerinck were less common in the case of Krakatoa, but all too common with most volcanoes, which kill their victims through accompanying earthquakes, toxic gas (usually sulphur dioxide) and smoke, and ultimately, burning. Over 1,000 people in the Ketimbang region were burned to death by the volcano’s superheated ash falling to the ground, which came to be known colloquially as “The Burning Ashes of Ketimbang.” The world, to use Winchester’s book’s subtitle, had truly exploded. As another captain, this one a Brit commanding a vessel called the Norham Castle, wrote in his log, “My last thoughts are with my dear wife. I am convinced that the Day of Judgment has come.”

Seventeen years later, in September of 1900, the city of Galveston, Texas became known to the world in a similar way to the Indonesian archipelago had been. The small city, situated on an island just off the coast of eastern Texas and 50 miles from Houston, had been getting hit with tropical squalls the entire summer, with one day reaching a record fourteen inches of rain within 24 hours, creating flood conditions. On August 28th, a ship out at sea made note of a powerful stormfront—now clearly a vortex—making its way across the Atlantic. Two days later, an agricultural chemist on Antigua named Watts reported that, “a thunderstorm sprung up to the southwest and came up over the land,” and that “while it lasted, it was very severe; the lightning was brilliant and almost continuous, while the flashes were very quickly followed by loud peals of thunder.” Over the next several days, the gathering storm passed through the Caribbean, moving over Cuba and then off the south coast of Florida, resulting in gale force winds in Tampa and Key West, but little else. Defying expectations thanks to a blockage created by a high-pressure zone over the Gulf of Mexico, the storm was then blown westward. Galveston was now directly in its path.

No one on shore knew what was coming, but the 30 passengers and crew onboard the Louisiana certainly had a notion on September 6th when they encountered the storm, which had now, unmistakably, become a cyclone. Captain T.P. Halsey had been paying attention to the rapid decline of the ship’s barometer and, despite his many years of experience, was not prepared for the storm’s intensity. As popular historian Erik Larson writes in his excellent book, Isaac’s Storm: The Drowning of Galveston, “horizontal rain clattered against the bridge with the sound of bullets against armor.” The wind was so intense that as it entered the nooks and crannies of the Louisiana, “it moaned among the cabins and corridors like Marley’s ghost.” As far as the passengers were concerned, Larson writes, “the ship seemed on the verge of disintegration.” It was not an unreasonable fear; as Captain Halsey put into his log, “I think the wind was blowing at the rate of more than 100 miles an hour.” It was, in fact, be 50 miles an hour greater, and Captain Halsey later amended his estimate, creating, in Larson’s words, “a hurricane of an intensity no American alive had ever experienced.”

Then, on September 8th, 1900, the storm finally made landfall. That is when the world for the people of Galveston ended. The effect was, as it often is with natural disasters, far more gradual than many might initially expect. It began with rising waters, much of it smashing against breakers, and washing onto the streets of the city, delighting many children who had never seen such things (Larson writes of many kids dancing in the flooded streets and creating rafts in which they could play the role of ship captains). Hundreds of adults came out to watch the spectacle of the storm and rising waters; one witness even recalled that “[a few people] appeared on the scene in bathing suits.” And yet, despite the gradual nature of natural disasters, they also tend to spin wildly out of control faster than anyone might expect. There just was not enough time for reality to sink in for many of the people of Galveston; Larson describes scenes bordering on the bizarre, of men walking to work as if nothing was out of the ordinary, despite “the occasional boy floating past on a homemade raft.” People continued about their day, and the water just kept rising.

The wind also kept gathering strength, which became impossible to deny. The roof of Ritter’s Café and Saloon was suddenly ripped off, with the accompanying pressure created by the wind, causing the ceiling to collapse on top of several diners, killing them instantly. A train traveling to Galveston was blown off its tracks, killing all 85 of its passengers. All the while, the water kept rising, moving from chest deep to neck deep in mere hours, sometimes minutes; houses became flooded and collapsed on top of entire families. At St. Mary’s Orphan’s Asylum, the ten religious sisters tied themselves to the 93 children under their care with clothesline. Only three of the children survived. It was later reported that the sisters had the children sing the hymn “Queen of the Waves” to soothe their fears as the water rushed toward them.

Within hours of the children dancing in the flooded streets of Galveston, the city had become a literal whirlwind of pure destruction. Erik Larson provides a horrifying summary of what was happening in the midst of the chaos:

Gusts of 200 miles an hour may have raked Galveston. Each would generate pressure of 152 pounds per square foot, or more than sixty thousand pounds against a house wall. Thirty tons. […] Powerful bursts of wind tore off the fourth floor of a nearby building, the Moody Bank at the Strand and 22nd, as neatly as if it had been sliced off with a delicatessen meat shaver. Captain Storms of the Roma had practically bolted his ship to its pier, but the wind tore the ship loose and sent it on a wild journey through Galveston’s harbor, during which it destroyed all three railroad causeways over the bay. The wind hurtled grown men across streets and knocked horses onto their sides as if they were targets in a shooting gallery. Slate shingles became whirling scimitars that eviscerated men and horses. Decapitations occurred. Long splinters of wood pierced limbs and eyes. One man tied his shoes to his head as a kind of helmet, then struggled home. The wind threw bricks with such force they traveled parallel to the ground. A survivor identified only as Charlie saw bricks blown from the Tremont Hotel “like they were little feathers.”

When the storm cleared, there were no illusions about the destruction it had caused. St. Mary’s University, along with three schools, were completely destroyed, as were 25 of the city’s 39 churches. Most houses were decimated, with only well-built mansions surviving relatively unscathed. The storm actually continued its destructive path across the United States, even killing a man in Missouri, and creating brushfires with its lightning strikes as far away as Massachusetts, and severe wind damage in New Hampshire. But the damage was most extreme in Galveston, with a staggering loss of life as high as 12,000, though likely closer to 8,000. This accounted for 20% of Galveston’s entire population and was deadlier than every hurricane that has struck the United States since combined and is considered—as of this writing at least—the deadliest natural disaster in American history.

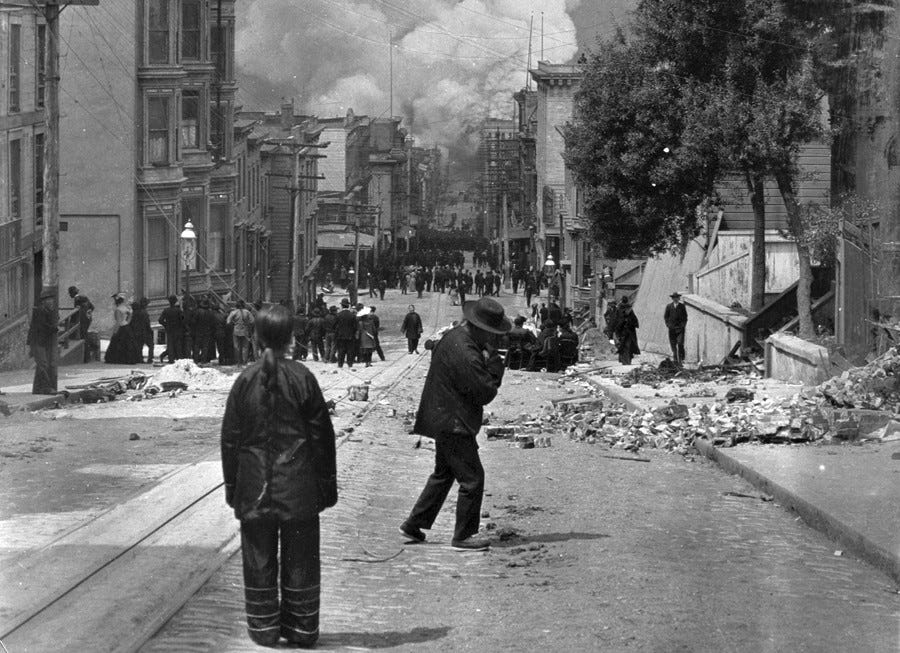

Six years passed. The devastations of Krakatoa and Galveston were largely forgotten by all except those who experienced them, if they were even regarded at all in places far away. One of those places was San Francisco, the largest city—one could even say the “capitol”—of the West Coast of the United States. It was a lively, bustling city, formerly the home of Mark Twain who, by then, owned 250 acres in Redding, Connecticut and was living out his twilight years. That would all change in the early hours of April 18th, 1906, when the earth beneath San Francisco began to convulse with what Simon Winchester calls “a great, ever-increasing, and uncontrollable violence”. There were several accounts written by people—most of whom geologists and scientists trained to write of such events in great detail—but the recollection written by the San Francisco Examiner reporter Fred Hewitt is the most harrowing on an emotional level. He had been walking home from his night shift at the paper when the tremors began at around 5:12 AM. Hewitt, having just stopped to speak to two policemen on his way, would recall what happened next as follows:

The hand of an avenging god fell upon San Francisco. The ground rose and fell like an ocean at ebb tide. Then came the crash. Tons upon tons of that mighty pile slid away from the steel framework and destructiveness of that effort was terrific.

[…]

I saw those policemen enveloped by a shower of falling stone. It is impossible to judge the length of that shock. To me it seemed like an eternity. I was thrown prone on my back and the pavement pulsated like a living thing. Around me the huge buildings, looking more terrible because of the queer dance they were performing, wobbled and veered. Crash followed crash and resounded on all sides. Screeches rent the air as terrified humanity streamed out into the open in agony and despair. Affrighted horses dashed headlong into ruins as they raced away in their abject fear.

Then there was a lull.

The most terrible was yet to come.

The first portion of the shock was just a mild forerunning of what was to follow. The pause in the action of the earth’s surface couldn’t have been more than a fraction of a second. It was sufficient, however, to allow me to collect myself. In the center of two streets rose to my feet. Then came the second and more terrific crash.

The street beds heaved in frightful fashion. The earth rocked and then came the blow that wrecked San Francisco from the bay shore to the Ocean Beach and from the Golden Gate to the end of the peninsula.

As if in sympathy for its immediate neighbor, the old Supreme Court building danced a frivolous dance and then tumbled into the street. Beneath that ruin of stone and brick were buried the two blue-coated guardians of the police to whom I had been talking a few minutes before. That few minutes, however, seemed to me a century.

That second upheaval was heartrending. It made me think of the loved ones in different portions of the country. It turned my stomach, gave me a heartache that I will never forget and caused me to sink upon my knees and pray to the Almighty God that me and mine should escape the awful fate I knew was coming to so many thousands.

Down Golden Gate Avenue the houses commenced again their fantastic, ogreish dancing. One lone line of frame buildings tottered a moment and then just as a score or more of terror-stricken, white-shirted humanity to reach the open, it laid flat [A set of flats on Golden Gate between Hyde and Larkin]. The cries of those who must have perished reached my ears, and I hope that never again this side of the grave will I hear such signals of agony.

Like it is with all earthquakes of all strengths, the earth’s shudders subsided almost as suddenly as they began. Aftershocks continued for a while after the two great convulsions, but the worst was, it appeared, to be over. However, the true horror had not even begun. There may have been a hint of it, with Hewitt describing “bedlam” unfolding almost immediately; “Mothers searched madly for their children who had strayed, while little ones wailed for their protectors,” Hewitt writes. “Strong men bellowed like babies in their furor. All humanity within eyesight was suffering from palsy. No one knew which way to turn, when on all sides of them destruction stared them in the very eye.”

But it was not just the violent upheaval of the earth that tore San Francisco apart. That was merely the foretaste for what was to come: all-consuming fire. The earthquake itself would ultimately be far less destructive than the blazes that ripped across the city for four days and nights that followed the shocks. As Hewitt concluded his April 20th, 1906 article,

Then an unnatural light dimmed the rising sun and the word went forth from every throat: “The city is ablaze. We will all be burned. This must be the end of this wicked world.”

From down south of Market street the glare grew and grew. The flames show heavenward and licked the sky. It looked as if the end of the world was surely at hand.

According to the centennial report from the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI), at least 80% (and as high as 95%) of the damage caused by the Great San Francisco Earthquake was caused by fires, which, in the words of a diplomatic telegram sent on April 25th, 1906, broke out “within five seconds of the shake.” These fires began in around 20-30 buildings, but quickly spread out of control thanks to ruptured gas mains, and even instances of the poorly-trained San Francisco Fire Department using dynamite on destroyed buildings in efforts to create firebreaks in order to contain the blazes. Local legend had it that one of the fires—the so-called “Ham and Eggs Fire”—was caused by a woman trying to cook breakfast with a broken chimney (though as Simon Winchester explains, “there is only circumstantial evidence, and not very much of that”). The famed writer and San Francisco native Jack London described what he saw in Collier’s a month after the event:

By Wednesday afternoon, inside of twelve hours, half the heart of the city was gone. At that time, I watched the vast conflagration from out on the Bay. It was dead calm. Not a flicker of wind stirred. Yet from every side, wind was pouring in upon the city: east, west, north, and south, strong winds were blowing upon the doomed city. The heated air rising made an enormous suck. Thus did the fire of itself build an enormous chimney through the atmosphere. Day and night, the dead calm continued, and yet, near to the flames, the wind was often half a gale, so mighty was the suck.

This observation really helps illustrate the true power—and true, existential danger—of wind when there is fire. The wind is always a friend of fire, thanks to its oxygen content, but also because when the fire has no more solid material on which it can feed, it still has the wind to carry it—via the remaining fragments of solids—to other feeding zones and begin the process all over again. What London was describing here is a firestorm, which is the worst possible scenario for anyone facing down an out-of-control blaze. The heat is beyond comprehension; nothing caught within such a thing can survive. The true horror of such a disaster can only be captured by remembering what had preceded it and what that, practically and logistically speaking, actually meant. Most often in fires, people die from smoke inhalation, but not always. And thanks to the earthquake that had led to the fires, many of the fire’s victims were still alive, but pinned under rubble or trapped within the collapsed buildings that lay in the path of the advancing mile-and-a-half long wall of flames. While some skepticism can be levied at such claims (thanks to a lack of concrete evidence), there were many stories told of policemen and other passersby, unable to save these poor people, putting them out of their misery with bullets to the head. Not that it mattered either way; as Simon Winchester grimly notes, “bodies consumed by fires that often reached more than 2,000 degrees would barely be recognized as bodies at all.”

By the time the fires caused by the quake were finally put out—in part, mercifully, by the all-too-common springtime rains that fall on the Bay Area—28,188 buildings had been destroyed and 490 city blocks were damaged. Many hydrants had been rendered useless by the quake itself, thanks to water mains becoming fractured all throughout the city. It had been the worst of all possible worlds, and this very quickly became clear to the hundreds of thousands of San Franciscans—over half the city’s population—had been made homeless. Well over 3,000 had been killed.

Mark Twain had become far less lively and gregarious in his later years, especially after his wife passed in 1904, and the events of April 18th, 1906, likely did little to brighten his increasingly darkened disposition. In the weeks that followed that destructive day, aid organizations had been formed, including one that brought together artists from California, and included a painting by Robert Reid called “The Spirit of Humanity”, which depicted a mother holding a child in her arms. Responding to this painting, Twain would write the following:

I keep thinking about that picture—I cannot get it out of my mind. I think—no, I know—that it is the most moving, the most eloquent, the most profoundly pathetic picture I have ever seen. It wrings the heart to look at it, it is so desolate, so grieved. It realizes San Francisco to us as words have not done and cannot do. I wonder how many women can look upon it and keep back their tears—or how many unhardened men, for that matter?

…

What connected these events? Nothing. Nothing literally, anyway. None of these events are related beyond a singular simple fact: that the human experience across time is beholden to forces we cannot control. Unlike the devastation caused by war, weaponry, or other man-made implements of destruction, the forces of nature are beyond the scope of anything within the human race’s locus of control. That control widens with time and technology, but nature’s influence remains constant, and it has an incredible advantage over those of us living within it (that is, all of us).

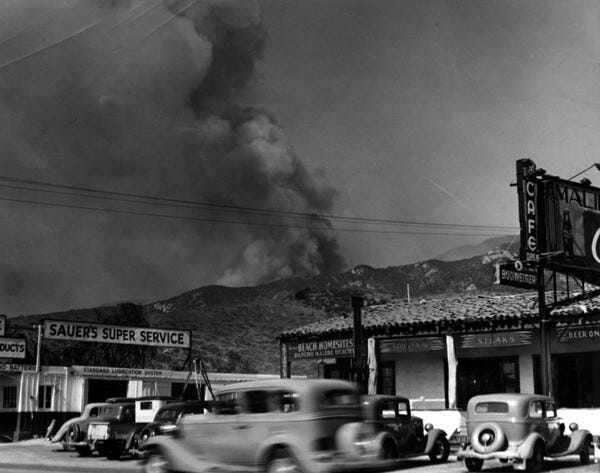

As of this writing, the Great Los Angeles Fires of 2025 has been continuing for over a week. There are signs of gradual containment, but the Santa Ana winds, dry conditions, and simple human fallibility are making things more difficult than they have ever been in modern times. The fires ravaging southern California are worse than any ever faced by Los Angeles in its entire history.

I have lived in Los Angeles for just over a decade. Wildfires are indeed a fact of life here, just as earthquakes are. We have not faced an earthquake even remotely close to the destructive 1906 quake, or even the 1992 Northridge quake. The fires of 2025 did not initially seem to possess the same frightening majesty as the fires of late 2017, especially with the memorable footage of the famous 405 highway being surrounded by flames as if it cut through the lands of Mordor. I remember when those fires occurred, I was able to see the curl of smoke in the distance from my apartment in North Hollywood, and even see a small finger of fire making its way over the ridge of the mountains ringing the San Fernando Valley.

It did not take long to realize that as dramatic as the Skirball Fire of 2017 had no doubt been, that what was occurring in the first week of 2025 was something different. I am no longer living in North Hollywood, but I still live in the San Fernando Valley, even more centrally-located, so my family and I can call ourselves extremely lucky (though still, in those early days of the fires, unnervingly surrounded by conflagrations to the south, north, and east; it should not have to be said, but the Pacific Ocean is to the west, making that direction not as reliable an escape route as it might otherwise be). As of this writing, however, the San Fernando Valley has remained relatively untouched, thanks largely to the direction of the wind blowing most of the smoke from the fire still engulfing the Pacific Palisades—the closest fire—out to sea.

The other fires, namely the Eaton Fire that consumed the majority of the lovely town of Altadena and the Hurst Fire that seemed intent on cutting off the Valley from more northern hubs like Santa Clarita, have seen major progress in their own containment. But one cannot escape the reality of such destruction, even when you’re safely tucked away in the safety of the Valley. Not when the smoke billows like a nuclear explosion over the mountains to your south, and the horizon of those mountains remains visible even at night thanks to the glow of the flames. And especially not when the stories—the constant, heartbreaking stories—of thousands of homes being destroyed by the forces of nature. And especially not when there are so many horrifying stories of the dead, which will only climb in number as time goes on.

The impossibility of trying to understand what is being faced by those of us living in Los Angeles County is what connects us to the stories of Krakatoa, of Galveston, of San Francisco, all around the turn of the 19th century, as well as all natural disasters that occurred before, and all natural disasters that have occurred since—from Vesuvius to Katrina (and to say nothing of the pandemics our species have faced). Natural disasters are the great equalizer of the human experience where we can viscerally feel what our forebears felt across time and space because, in the end, we are all living on the same planet that cares about each and every one of us in equal measure (that is to say, not one iota). Natural disasters are also the great equalizer of understanding the human mind, because, despite differences in scale and kind, there is no meaningful difference between a human being living in 1883, 1900, or 1906, and a human being living in 2025. And human beings across time do the same thing in the face of existential horror: they ask why and search for ways to provide a satisfying answer.

Throughout most of human history—and no doubt well into the present—humans often turn to gods to explain suffering on the scale of such calamities; “what did we do to anger them/him so?” Book Four of the Sibylline Oracles, part of a series of medleys allegedly uttered by Greek prophetesses in states of religious fervor, composed after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius and the destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79 CE, proclaimed in part:

When a firebrand, turned away from a cleft in the earth

in the land of Italy, reaches to broad heaven

it will burn many cities and destroy men.

Much smoking ashes will fill the great sky

and showers will fall from heaven like red earth.

Know then the wrath of the heavenly God.

Plenty of other examples of divine explanation litter the history of humankind and its encounters with nature’s destructive tendencies, including the events described earlier in this essay. As Simon Winchester explains in his book about the eruption at Krakatoa in 1883, the people of Java firmly believed that “Each volcano has a god […] and he readily displays his anger with earthly conditions by spewing forth fire and gas and lava.” And thanks to the sheer scale of Krakatoa’s destruction, this faith later transitioned toward Islam. Mass-scale, natural destruction was (and is) thus often framed negatively—usually by proclaiming a volcano, a flood, an earthquake, or any other calamity to be “god’s judgment.” This notion is also found in a letter written by Mormon Elders published in the Deseret Evening News in 1900 after the Galveston hurricane:

After we had talked with the people for a while, we went to see the damage that was done, when, to our astonishment, we found about half of the city in ruins, and dead and wounded on every hand. We thought we had witnessed scenes before that were heart-rending, but it was terrible to behold men, women and children lying all around us dead, either drowned or killed by the falling houses. They were hauling corpses in by the wagon loads, and they were disposed of like so many hogs, rich and poor, black and white, together; it made no difference.

…Whether God brought this destruction upon the city for its wickedness, we are not to judge.

While not completely content to damn the residents of Galveston, the fact that celestial damnation was considered at all is noteworthy, in the context of the human tendency to look for explanations for the unexplainable. There was actually resistance to classify the Great San Francisco earthquake as something divine, but not from the everyday people who had survived it. Historian Joanna L. Dyl has written at length about this in her 2017 book Seismic City: An Environmental History of San Francisco's 1906 Earthquake, in which she explains that business owners (and later politicians trying to attract businesses to the Bay Area), “emphasized the effects of the fire over those of the earthquake.” Elaborating, Dyl writes:

Most policies covered fire but not earthquake damage, complicating the situation. The emphasis on the role of the fire over that of the earthquake was often strategic—a means of countering early media reports that the quake had completely destroyed San Francisco and forcing insurance companies to pay. The first insurance adjusters on the scene reportedly believed that the fire had done no more than burn an already ruined city.

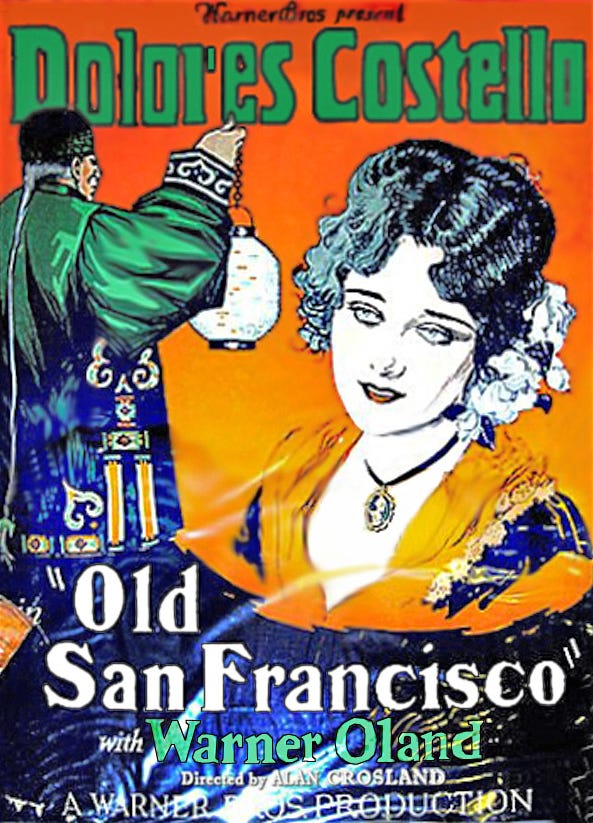

In retrospect, we know that this was not the case—again, at the bare minimum, the fires were responsible for 80% of the city’s destruction. But the point remains: there was a concerted effort to downplay the reality of living (and investing) in a city that lay on top of land prone to violent upheaval, and any claims of god’s will were being largely ignored by those concerned with giving and receiving payouts. However, this effort did nothing to quell notions, even many years later, that the destruction visited upon San Francisco was due to divine anger, especially in the wider culture. In the 1927 silent film classic Old San Francisco, religious overtones pepper the thrills. At one point, the film’s villain Charles Buckwell (played by Warner Oland, a Saami-Swedish actor known for his yellow-face performances—this film being no exception—including the fiendish Dr. Fu Manchu) is seen carousing a bar, and a man bursts in raving, “"In the midst of thy inquities, God will punish thee! His wrath will fall from Heaven!” The earthquake does indeed occur because this is 1906, and the villain is killed by this earthquake, serving as divine justice. While the film’s fearmongering over white slavery certainly does not age well and was likely the main concern of famed producer and studio executive Darryl F. Zanuck and his screenwriter Anthony Coldeway, the emphasis on divine wrath via natural disaster is unmistakable.

The point being, this tendency to ascribe heavenly purpose to existential devastation is not a bug in human nature; it is a constant. The need for explanation has always been present, often placed in the hands of god or gods, or, in more recent times, in forces greater than ourselves. This can be seen not just in the commentary that surrounds natural disasters that have occurred in the 21st century—especially with hurricanes and wildfires that have occurred—but with our own cinematic trash. Who else remembers the 2004 “classic” from the disasterpiece maestro Roland Emmerich himself, The Day After Tomorrow? When one realizes that the social effects natural disasters tend to be essentially universal across time and space, it is difficult to see vague implorations and edicts to clean the environment as anything other than hypermodern appeasements to an angry, ineffable god.

In the days, weeks, months, and likely years that follow the Great Los Angeles Fires of 2025, the term “climate change” will be tossed around like an incantation. Much as I have sympathy for this as a simple statement of systemic fact, one could be forgiven at this point for demanding more than verbal talismans that do more to signal ideological identity than to offer meaningful solutions. After all, saying that “climate change did it” offers small comfort to the citizens who lose their homes (or lives) to mother nature’s wrath—something as impossibly intangible as the will of god. It does not explain the inability to fight the blaze and get it under control within a week. It does not explain why zero desalination plants and zero water storage facilities have seen the light of day since being approved over ten years ago. It does not explain why the mayor of Los Angeles could not use the sixteen hour flight back from Ghana to come up with some kind of answer for why she saw it fit to make the trip, despite promising she would never do such a thing. Just as acts of divine justice do not explain these things, neither does a broad diagnosis of climate change.

In truth, name-checking climate change does provide some solace, at least for those saying it: it allows for emotional catharsis; it allows for some kind of judgment. What else follows the “climate change” invocation other than an accusation that “only one party” in the United States believes it is even real? Certainly not an explanation for why a state in which the party that does believe climate change is real was so incapable of preventing such a thing from happening, much less fight it when it does. And certainly not any kind of practical prescription for how such things can be prevented in the future, either in California, in the United States more broadly, or especially at a global scale. This is what blind trust in un-cited, phantom experts truly looks like: a complete inability to do anything other than point to a calamity, say that it is the fault of an unseen, implacable, and unknowable force, and shake one’s head at the stupid humans who do not accept that such a thing exists. Are we absolutely certain that god and climate change are not synonymous in the minds of such folk?

None of this is to say climate change (both natural and man-made) did not play a part in the 2025 wildfires; it almost certainly did, as most extreme weather events tend to be. What it is to say is that the invocation of climate change, having lost all tangible meaning in all but the most precise and scientific explanations, is part of the general pattern in which humankind perpetually engages in the face of annihilation by its own home: it is a way to explain what is and will always be bigger than us, and thus, what cannot be stopped. This, at some level, is why every single natural disaster faced by a significant swath of humanity—from cities to nations—tends to produce effects that seemingly have nothing to do with the disaster in question.

In 2020 and in 2023, I released two episodes of History Impossible that dealt with two of the most destructive pandemics in the history of humankind: the so-called “Spanish flu” of 1918-1920, and the Black Death of 1346-1353. A major theme shared by both of these episodes—both of which I am still very proud of—were the human effects of these calamities. By that, I mean to say the effect those calamites had on how people behaved, especially once they were over. If it was not clear from the tone I took just a few paragraphs ago while listing off examples of what I personally see as failures of governance in California, I am already experiencing what I described in those episodes and what I am describing now. I am looking for something—for someone—to blame. This is normal. This is human. Despite my observation of this tendency appearing to be from 30,000 feet, I am not above experiencing it myself. This is not to say that it is therefore good that I or anyone else (especially those who have lost their homes or, god forbid, their loved ones) am/are doing this. It oftentimes is not; it is certainly not helping quell the blaze over the mountains to my south. However, it is to say that this impulse is, in all likelihood, inevitable. Like the destructive force of nature, and our ascription of divine purpose (whether in the form of god’s wrath or the consequences of anthropomorphic climate change), this need for earthly judgment is likely eternal.

It might feel trite to say, but people get affected by nature and despite the tremendous human suffering that defines these experiences, it is the downstream effects that are what ultimately matter most to the study of history. This is what the subfield of environmental history seeks to explain when it is at its best. This can be seen in all of the events with which we began this essay.

In many ways, significant political events were already unfolding in the East Indies by the time of the Krakatoa explosion. The Dutch colonists who ruled over much of the islands had been gradually losing their influence, largely due to the faltering imperial colonial spirit back in the Netherlands, that had gone hand-in-hand with the publication of a book known as Max Havelaar; or, The Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company, written (at first pseudonymously) by a colonial official named Eduard Douwes Dekker who had become disgusted with Dutch colonial practices in the East Indies. He essentially blew the whistle on the entire colonial enterprise in the most lucrative part of the empire, revealing a brutal regime of serfdom that bordered on slavery. This outraged the Dutch public, who, it seemed, truly had no idea that colonial practices were what they were. This resulted in reforms passed by the Dutch parliament that were ultimately “too little, too late,” to use the words of Simon Winchester, and “not enough to still the nationalist mood [growing among the East Indies natives.]”

When Krakatoa exploded, as mentioned earlier, much of the Javanese and other peoples of the East Indies still held onto traditional religious beliefs. These beliefs did little to catalyze anything resembling nationalism or the spirit of revolt; at least compared to the previous occupying forces of Islam, whose religious spirit had remained across the centuries. A shift away from traditional religious beliefs and toward a fealty to Islamic values. As is often the case in Islamic history, this took on a political dimension, and, in the words of Winchester again, focused on ending the “poverty, alleged colonial tyranny, corruption, [and] the unbearable heaviness of the imperial yoke,” created by the Dutch presence in the region.

This resulted in the Islamic radicals in the Indonesian province of Banten beginning to carry out violent strikes against the colonial authorities the same year Krakatoa exploded. Continuing, Winchester writes, “An examination of the events that began with this pair of attacks on the colonial military in the autumn of 1883 suggests that the driving force behind most of the subsequent violent events in west Java […] was without a doubt fundamentalist, militant, anticolonial, anti-infidel Muhammadanism.” These types of attacks continued for years, culminating in the 1888 Banten Peasants’ Revolt, which, to quote Winchester again, “is thought by many today to be a turning point in the region’s colonial history.” These events—and arguably the eventual liberation of Indonesia in 1949—likely could only have occurred thanks to the rise of Islamic influence in the region, which, in turn, could only have occurred thanks to the mass conversions that were incentivized by the eruption of Krakatoa and the natives’ abandonment of their traditional folk beliefs that had failed them at their greatest time of need.

In the case of Galveston, things were far less grand in scope, but no less consequential. The first sign of downstream consequences came in the form of an editorial written in the Houston Post criticizing the Weather Bureau’s ability to both predict and track the hurricane. This was indeed true. In the Bureau’s own forecast for the day of the hurricane—which killed thousands, it is important to recall—claimed that it would be a “fair, fresh, possibly brisk” day, with “northerly winds on the coast” of East Texas. The editorial was merely condemnatory in its reporting of the facts, and yet, the Bureau’s chief meteorologist Willis Luther Moore wrote an angry letter to the Post, acting as if he and his Bureau had been defamed. While it would be fair to say that people working within the Bureau on the days leading up to the hurricane did not know the scale or position of the hurricane, there were plenty of employees who expressed private concerns that the information they were receiving made it clear that what was coming was no mere tropical storm.

Thanks to the speed and manner in which information traveled in 1900, the reputational damage was contained, especially as Moore went on a public relations scramble and was able to spin the narrative as he saw fit. It became something of a mantra for him to see Galveston as a once-in-a-millennium occurrence, later writing that “Galveston should take heart, as the chances are not once in a thousand years would she be so terribly stricken.” It is of course true that no hurricane would match the destruction wrought by the one that fell in 1900, and yet a massive hurricane struck the city again in 1915, overcoming the massive sea-wall that had been completed in 1910.

Eight further storms struck the city, with the biggest one occurring in 1961 and forcing an evacuation of a quarter million people from the surrounding area, while four tornadoes created by the hurricane leveled 120 buildings. Every single time, the people of Galveston and the wider United States were shocked by how such a thing could happen. The memories of the 1900 storm were long-dead, buried by Willis’ PR campaign, and there was no better understanding of how dangerous hurricanes were for generations; as Erik Larson writes in Isaac’s Storm, “people seemed to believe that technology had stripped hurricanes of their power to kill.” While it would not be fair to say for certain that this flippancy led to greater casualties in later storms like Hurricane Katrina, it is fair to say that the agency tasked with forecasting such things, thanks to its chief that oversaw the failures in the 1900 storm, pretended to possess credibility it never truly had for much longer than it should.

As is often the case, business interests seemed to be the only ones who saw the writing on the wall and adjusted their investments. This created the true, measurable downstream effects on Galveston, and the people who lived there, ending the city’s previous economic boom that had lasted since 1875. The only reason the city did not completely fall to ruin, funny enough, was Prohibition, which caused Galveston to become a hub for bootleggers and gambling dens. While this saved the city from going the way of Detroit in the 21st century, it was likely small comfort to the people who still wanted to live and make an honest living there, and who wanted nothing to do with the encroachment of early 20th century organized crime.

However, the most noteworthy cases of downstream effects—at least from where most Californians and I are sitting—are the ones experienced locally, nationally, and even internationally, in the aftermath of the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906.

In the case of San Francisco, we already saw the downstream effects outlined by Joanna Dyl, in which efforts to downplay the importance—and even reality—of the earthquake and of quakes themselves by people who lived and operated in the area. Simon Winchester makes a similar point, describing “a singular effort […] to convince people across America and around the world that the city’s suffering was not the result of an unpredictable caprice of nature.” Winchester notes that, at the end of the day, cities including San Francisco always recover from the setbacks created by catastrophes like earthquakes because “before long the original reasons for a city’s existence reassert themselves.”

However, in the aftermath of the Great San Francisco Earthquake, “draconian pronouncement[s]” were made by the city’s Mayor Schmitz that amounted to unofficial martial law for years, which involved both local police and federal troops executing looters on the spot. This was only the beginning of what many in normal circumstances would recognize as negative downstream effects of the disaster. Suicides, most of them almost certainly related to financial troubles created by the quake and the drama that often unfolded thanks to insurance difficulties, increased. While there was a rush to “pay all claims” (to use the words of London insurance underwriter Cuthbert Heath in a telegram), 90,000 San Franciscan citizens and companies made claims within 48 hours of the fires being extinguished, creating “confusion and consternation […] on all sides,” to use the words of Simon Winchester. Many people simply lost their policies and, thus, their livelihoods.

This was particularly felt in the city’s now-famous Chinatown, where the mostly-uninsured and concentrated Chinese American population was now business-less and homeless. Not giving a damn where the Chinese themselves would like to go or do, a committee was formed that, following the wishes of most non-Chinese San Franciscans, aimed to ghettoize the Chinese first in a concentration camp at the bottom of Van Ness Avenue, and then, as described by Winchester, “to what had long before been planned for them, an ‘Oriental City’ out at Hunter’s Point, a bleak peninsula to the southeast of the city.” The desire to rid San Francisco of Chinese people, and obviously anti-Chinese racism, long pre-dated the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 (lest we forget the antics of Denis Kearney three decades earlier), but the destruction provided a useful catalyst to try and make this happen. It ultimately did not succeed, but only thanks to the Chinese Americans themselves refusing to be relocated and to the actions of the Chinese legation in Washington, D.C., backed the Empress Dowager Cixi herself, reminding the local government that Chinatown’s land was technically owned by the Chinese government, where they intended to rebuild their consulate. Thanks to the incredible economic damage this would cause, the committee admitted it cared more about trade than it did about so-called ethnic purity and accepted defeat.

However, this victory would prove a hollow one. Thanks to the destruction of 1906, thousands of immigration records were destroyed, thus allowing many Chinese American men to claim citizenship as part of an effort to bring in the rest of their families they had left behind in China when they came to the United States looking for greater opportunities. Amendments to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 had included what Simon Winchester called “a liberalizing clause” that allowed for this. Thanks to rapid swelling of Chinese immigrants coming into Angel Island (the so-called “Ellis Island West”, as envisioned by the Bureau of Immigration), inevitable suspicion began to arise on the part of U.S. government officials. As Winchester explains, “Angel Island fast became notorious as the place where the American government tried hard to identify them, exclude them, and not welcome them at all.” Given the circumstances in 2025, it is hard not to sympathize with officials trying to stem the tide of unprecedented numbers of undocumented immigrants trying to overcome the already-liberal system in place. This led to a complete gumming-up of the immigration system in the Western United States, with some detainees being held in the hastily-erected concentration camps for years.

These conditions were, in part, what later informed the basis of the Immigration Act of 1924 (also known as the Johnson-Reed Act), which included the National Origin Act and, most tellingly, the Asian Exclusion Act. Not only did this collection of laws explicitly prohibit the immigration of people from Asia until the Hart-Celler Act passed in 1965, but it established extremely strict quotas upon the number of immigrants coming in from Eastern and Southern Europe. This latter point is especially significant in the context of what began to occur less than a decade after the passage of the Immigration Act: the rise of the Third Reich and the ratcheting oppression and eventually murder of Europe’s Jews. While there were plenty of other legislative and executive barriers to saving the Jews from Hitler’s racial purification project, the quotas put in place by the Immigration Act made it impossible for Europe’s Jews to escape in sufficient numbers to save themselves. Hindsight is indeed 20-20, but had the quotas not been there in the first place, the destruction of European Jewry might not have been so complete. This was by no means solely connected to the after-effects of the Great San Francisco Earthquake, but that calamity, by then a distant memory, certainly had pushed things along in such a way that made those dark consequences more likely to occur. In other words, it is not unfair to characterize the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924 and its subsequent consequences as being a significant indirect consequence of the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906.

However, the biggest and direct long-term consequence that came from all the destruction facing San Francisco was a relatively simple one: it would no longer be the go-to city of the American West. That honor, within a decade, would go to where I am writing this essay and where fires are destroying tens of thousands of acres: the city (and county) of Los Angeles. This can certainly be seen with the rapidly burgeoning film industry, whose success in the early 20th century was like a rocket, and carried with it its own effects. However, it would be a while before the studios that made up Tinseltown would relocate their offices from New York City to their new (and current) home. Investments in the land had yet to be made in 1906, but it was already being eyed by outsiders, such as the British consul general Sir Courtney Bennett. This could be seen in a telegram he sent his superiors back in London, which, in the words of Simon Winchester, captured “his gloomy mood” regarding San Francisco’s future. This was thanks to “the insurance debacles[,] the strikes and riots that he felt were now gripping the city, […] the fractious and disputatious mood of the place, and how even the local press was abandoning its eternal optimism and beginning to ask questions about the city’s long-term future.” This was only five months after the earthquake and the fires, when Sir Bennett wrote the following:

The moral effect of the earthquake has been great, and would-be investors are wondering whether there are not places other than San Francisco where money might not be more profitably invested. A man naturally hesitates to put up a million dollar building when it may be shaken down at any moment. […] A building could be put up in Los Angeles […] for thirty percent less than in San Francisco.

As Simon Winchester concludes, “this, in essence, is what then happened.” The rest, as they say, is history.

…

These examples have nothing and yet everything to do with the calamities nature threw humanity’s way. The reason for this is, if we are being charitable, what is often implied (perhaps unintentionally) when people invoke climate change as a significant danger to our planet. The specificity and prescriptive power that is lost in those invocations are certainly not lost when looking at the big picture of how nature and mankind are truly intertwined, no matter how much distance we put between ourselves and those natural forces through technology, economics, and governance. This is made obvious when mankind is forced into what no so many thousands of years ago (in the grand scheme of things) was seen as his or her natural state. As incredibly useful as science has been to our growing understanding of our universe and even ourselves, it seems to have fallen short—at least among the general public—at reminding us of this fact. Plenty of literature and other forms of art have never lost sight of this. Look no further than arguably the most incredible scene from the underrated 2012 survival thriller masterpiece, The Grey:

This scene is powerful for all sorts of reasons, not least of which is Liam Neeson’s always-incredible acting chops, and for seemingly resolute atheistic subtext, culminating in Neeson’s gruff final words: “Fuck it, I’ll do it myself.” However, what the scene reveals is, whether there is a god cruelly ignoring the character Ottman’s pleas or not, we are on our own here, and here is, however harsh it might be, is indeed our home, to paraphrase Carl Sagan. When we understand this, which I believe we can when we look at stories like those described in this essay (including the Great Los Angeles Fires of 2025), the thrust of history at the grandest scale can be understood with the minutest detail. Environmental historians have observed this since the 1960s, carrying the torch of the godfather of environmentalism, Aldo Leopold, who first made the case that history should be examined from an ecological perspective in 1949. Much has been written from this perspective—too much to cover at any length here—but it was most compellingly explored in recent years by the incredible historian J.R. McNeill.

In his 2010 work, Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914, McNeill offers a sweeping look at the modern history of the Caribbean region of the Western hemisphere, and comes away with a conclusion that has yet to face a compelling rebuttal from other historians. That is, that the colonists of the New World did not just broadly benefit from the role of novel infectious diseases largely carried by mosquitoes, but that in particular instances it did as well. Ranging from determining the outcomes of several battles between the Spanish and the English, to battles of the Revolutionary War, to the efforts of expanding the American empire at the turn of the 20th century: natural disasters—in this case, disease—continued to weight the outcomes in one way or another. In addition, the spread of these diseases was by no means “conscious” or a “spur of the moment”; as McNeill notes throughout his work, human agency always had a part to play. As he writes, “outbreaks were not random except in their timing [and they] formed a regular pattern that constrained randomness, and severely narrowed the range of likely outcomes of the political struggles in the Greater Caribbean.” To put it simply, the environment acted upon the people within it, and the people within it acted upon the environment; new worlds were thus created.

Scale this relationship however one wants and it applies to every single story described in this essay as well. These were all cases where human agency was completely absent in the destructive events themselves, and yet, given our propensity for seeking meaning and finding someone to be held to account, human agency comes roaring back. Whether it is an anti-colonial jihadist uprising in the East Indies, the rise of organized crime in an east Texas coastal town, or the collapse of influence of a west coast city and nativist resurgence in the politics of American immigration—human agency would find a way to reassert itself in the face of true existential crisis. The likelihood of this happening again in the wake of the Great Fires of 2025 is by no means a guarantee, but to say it is unlikely is, in my view at least, to bet against the house.

In his 1998 book, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster, the late great socialist historian and urban theorist Mike Davis described Los Angeles as an “Apocalypse theme park,” and wrote a still-controversial chapter entitled “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn,” which inevitably became relitigated in the wake of the Great Fires of 2025. In this chapter, he describes another one of Los Angeles County’s most infamous fire disasters, the Malibu wildfire of 1930, in which walnut pickers accidentally caused a blaze that consumed over 15,000 acres of land along the world-famous beachfront. While today it seems conventional wisdom that the stretch of coastline moving down from Malibu into what is now the Pacific Palisades and Santa Monica should be populated with thousands upon thousands of homeowners—mostly wealthy—it was not always the case. As Davis writes:

In hindsight, the 1930 fire should have provoked a historic debate on the wisdom of opening Malibu to further development. Only a few months before the disaster, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.—the nation’s foremost landscape architect and designer of the California state park system—had come out in favor of public ownership of at least 10,000 acres of the most scenic beach and mountain areas between Topanga and Point Dume. Despite a further series of fires in 1935, 1936, and 1938 which destroyed almost four hundred homes in Malibu and Topanga Canyon, public officials stubbornly disregarded the wisdom of Olmsted’s proposal for a great public domain in the Santa Monicas.

Davis makes a compelling case that the desire for mass, high-class, profitable development—which lies in the hearts of not just real estate developers, but also California’s politicians of both parties over nearly a century—has overridden basic, common sense.

While there are many complicating factors for explaining the infrastructure shortfalls faced by Southern California in the first weeks of 2025, as explained very well by Matt Welch over in Reason, this tension has, as best I can tell, often sat at the core of California’s political rot vis-à-vis the problem with our inability to intelligently face natural disasters. After all, there are still-unrealized projects involving water reclamation that date back to the Eisenhower administration, and corruption involving water sources was used as a plot device in the magnificent film Chinatown back in 1974.

While I do not necessarily agree that greed and real estate development in and of itself is the problem facing Los Angeles, I do believe that the inherent tension created between rapid real estate development, profit-seeking, and common sense fire prevention and fighting methods has created a flawed incentive structure that has been recognized by figures like Davis for decades. This is one of the other ways human beings face down the inexorable crush of mother nature: denial. This was seen in the Weather Bureau’s obstinance following the Galveston hurricane in 1900, and it has been seen in many other instances since, and as we have seen, that has a way of playing into the downstream effects of natural disasters throughout history.

Making use of pop culture—particularly cinema, one of my favorite rhetorical avenues as well, if it was not obvious enough by now—Davis writes that, “The City of Angels is unique, not simply in the frequency of its fictional destruction, but in the pleasure that such apocalypses provide to readers and movie audiences. The entire world seems to be rooting for Los Angeles to slide into the Pacific or be swallowed by the San Andreas fault.” It has been differing levels of tiresome to hear non-Angelenos complain about Los Angeles from the outside for the decade that I have lived here, but it has also been completely understandable because many of us recognize the absurd situation in which we live (at least those of us who see living on a fault line and in a high fire hazard region of the country as self-evidently absurd).

However, it is difficult to avoid the feeling that now, finally, the people of Los Angeles may no longer be persuaded by the power of denial sold to them by the politicians who seem to be more concerned about cultivating real estate developments and investments than they do about preventing mass-swath destruction of those investments. After all, if they can simply say “climate change” and point to the other party that they claim does not believe in climate change, there is nothing further for them to do other than to facilitate rebuilding efforts. The question is whether or not voters—or, for that matter, investers—will continue to tolerate that. It is difficult to say. But the idea that nothing will happen is a tall order indeed. The “something” that could happen could be anything from another recall election—this time of our brain-frozen mayor—to a fragmentary flight of different studios to ostensibly greener pastures like Atlanta, Austin, and Las Vegas. It is impossible to say, but it is hard to believe nothing will change, given all the examples throughout history that we have covered here.

There is, I suppose, some comfort in the notion of creative destruction; I suspect that is why so many historians have tried to reframe Genghis Khan as a creative force, rather than one that, via extreme violence, depopulated the planet enough to reduce humanity’s carbon footprint. I share our historical podcast Grand Puba Dan Carlin’s moral concern with such claims because it is all well and good to say, eight centuries later, that the world is better off because of such disruptions, but it is small comfort to those who lived through them. We, however privileged we are not to be slaughtered by hordes on horseback, are those living through such disruptions in the 21st century. I must remind myself of that when I say all of this, in an effort not to be too insufferably sanguine; we, at least those of us living in Southern California, are almost certainly facing a period of change, perhaps profound change, just as our forebears did in the face of destruction, via volcano, hurricane, or earthquake. I just hope that we have an appropriate perspective in facing it, one that appreciates the scale on which we all exist.

I think Simon Winchester, who I have quoted a lot in this lengthy essay, put it best when he described what Neil Armstrong must have felt as he stepped out on the lunar surface in 1969 and stared up into the star-studded blackness of our universe. As Winchester writes:

What he saw—and what we saw through his eyes, which we now perhaps take somewhat for granted—was a thing of incredible and fragile beauty. It was a floating near-spherical body, tricked out in deep blue and pale green, with the white of polar ice and mountain summits, with great gray swirls and sheets of clouds and storms, and with the terminator line, that divides darkness and light seeming to sweep slowly across the planet’s face as it turned into and out of the sun. It was a lovely aspect to contemplate. And it was a view that in time compelled humankind to take stock.

Excellent and thought provoking as usual.