Understanding the Abyss: Holocaust Scholarship in the 21st Century

Another historiography, and an even more important one

What you’re about to read is the second piece of historiographical research I have conducted during my time in graduate school (with another piece to likely come by the end of the semester). This was the capstone to my study of modern European history in which I examined the trajectory of Holocaust scholarship following the early 1990s to see how it ended up where it currently exists in the 2020s.

It might seem like a no-brainer for why this subject would be of interest to me, but in truth, I had not read much of the works I covered in this paper, apart from Ordinary Men by Christopher Browning and The Holocaust: An Unfinished History by Dan Stone, which served as the beginning and end points of this paper’s scholarship, respectively. I have read plenty of other works about the Holocaust over the years, but it had mostly been related to basic facts/timelines, overall Third Reich history, ideological justifications felt by the Nazis, and ancillary locations in which it took place (e.g. Yugoslavia).

As I came to understand while doing the research for this paper, it was not until relatively recently that sincere questions of “why” began to be more fully appreciated; not so much “why did the Nazis hate the Jews?”—there are plenty of primary source documents explaining that—but rather, “why did the Nazis go about ridding the world of Jews the way that they did?” and “why did ordinary Germans—including in the military—go along with such a murderous program?” The short, quasi-simple answer, it seems to me, is because they wanted to be and ultimately were happy to be part of something. Plenty of far smarter scholars than me have fleshed out that conclusion, as will be seen in the essay that follows. This goes a long way to humanize the Germans in a way that doesn’t veer into performative and loaded “empathy” and helps us understand the way ordinary people become radicalized into obscene ideologies and cults, and do obscene things to support them.

Holocaust scholarship is both wide and dense, making it difficult to do a full-on historiography, but focusing on the efforts made in the 21st century struck me as a good way to have some perspective on how such a well-trod subject is addressed as the final survivors of the genocide pass on. Where things go from here is anyone’s guess; I find it difficult to imagine that revisionism of the kind we are used to will ever be truly en vogue (one hopes), but the path toward understanding ordinary people’s complicity seems to be a fruitful one.

Anyway, please enjoy this next installment of a History Impossible historiography.

…

The question of “why” continues to plague historians of the Holocaust. Why did it happen? This is an understandable impulse, given how unthinkable such an action—the deliberate mass murder of over ten million civilians, among them six million Jews—actually was. While there are no shortages of examples of genocide in human history, it was not until the Holocaust was ended with the destruction of the Third Reich, the victorious Allied forces began to take account of the destruction the Nazis had wrought, and many of the remaining leaders began to be brought to justice that the term “genocide” even became an official criminal classification. That classification was part of the process of understanding why such a thing occurred, and while it certainly provided an enduring judicial baseline that lasts until the twenty-first century, the question of “why” the Holocaust happened the way it did and even happened at all continue to be asked. As the generation of survivors continues to pass away, and more mainstream knowledge of the Holocaust continues to dwindle, it has become increasingly important to keep the scholarly examination—and debate—of and about the Holocaust alive. If “never again” is to mean anything, it is to mean that never again must we allow the truth of the Holocaust to be uncertain. Centering the debates within Holocaust historiography itself can both strengthen future scholarship and serve as an inoculation against the push for revisionism and denial of one of modern Europe's greatest crimes.

In the decades that followed the conclusion of the Second World War, and as the extent of the Third Reich's crimes became better-known, the debate among historians of the Holocaust became centered on whether or not the mass killings of Jews and other victims was part of the Nazis' original intentions or a function of the war itself. This debate has largely been resolved in favor of the “intentionalist” school of thought, at least outside of revisionist circles. However, a new debate began to take shape in the early 1990s after the publication of Christopher Browning's celebrated Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. Since it had largely become settled that genocide was an intended policy rather than a byproduct of the realities of war, the question of “why” such an intent even formed in the first place. Browning's overall thesis was a simple, if disturbing one. Namely, that the Final Solution was conducted by, as the title of his book suggested, ordinary Germans, and not necessarily ones motivated by bigoted bloodlust; rather, as demonstrated by their initial revulsion at such a task followed by their near-total collective choice to take part, it was motivated by social conformism. Four years later, this was loudly challenged by political scientist Daniel Jonah Goldhagen in his book Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust, which argued that not only was anti-Semitism the true core reason for ordinary Germans' participation in mass murder, but that it was an ingrained cultural tradition of anti-Semitism unique to the Germans, making an arguably essentialist argument.

By 2024, historians had largely moved on from singular emphases on either the social psychological explanations or the purely historical-ideological explanations for why the Holocaust occurred the way it did. This could be seen in the synthetic approach that had begun to take shape in the previous decade, and the addition of one more analytical framework—that of historical memory. With the publication of Dan Stone's 2024 work, The Holocaust: An Unfinished History, it became clear that historians of the Holocaust had not only synthesized the two schools of thought put forth by Goldhagen and Browning, but also added a fundamental question to their analyses: how was, how is, how will, and even how should the Holocaust be remembered by future generations of historians? Based on the arguments that began to take shape in the mid-2010s, it is clear that many historians see the Holocaust as a warning for how easy it can be for humans to cause others to suffer in the name of an ideology. However, for this to happen, the conversation needed to begin, and it did not begin in earnest until the 1990s with the publication of two books with competing visions on the same subject, that generated far more controversy than many historians likely expected.

Christopher Browning's Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland is a significant work in the field of Holocaust scholarship thanks largely to its disturbing answer to one of the most enduring questions about the Holocaust: why did so many seemingly ordinary Germans—non-invested, non-radical—take part in the killing of so many Jews while so few did not? While forming and ultimately answering this question, Browning examined the court indictments of Reserve Police Battalion 101 of the Ordnungspolizei, and came away with a profoundly disturbing conclusion: that the majority of men of this battalion—and by extension, many of the men who took part in the Holocaust—did so thanks largely to the social pressure placed upon them; by the regime, their superiors and their brothers-in-arms, and ultimately, themselves. Citing the famous research conducted by psychologist Stanley Milgram, Browning writes that, among other factors, “conformity assumes a more central role than authority,” and that, “the mutual reinforcement of authority and conformity seems to have been clearly demonstrated,” both in Milgram's experiments and, by extension, in the actions of Reserve Police Battalion 101.1

Browning is careful not to discount ideological factors in explaining the actions of the Third Reich against their victims, writing that the orientation of the different police battalions in Poland were “certainly not free of ideological exhortation.”2 He also makes it clear that Reichsfuhrer-SS Heinrich Himmler was enthusiastic about ideological purity of his SS and the Ordnungspolizei via their intensive training and exposure to propaganda. He takes pains to point out that the younger men in these battalions were essentially incubated in Nazi society and thus, Nazi ideology; ideology was, in that sense, vital. That vision, linked to the crime of the Holocaust and the desire of figures like the members of the 101, is what defined the German people's complicity in it. However, even in emphasizing the importance of Nazi ideology, he makes it clear—thanks in part to the propaganda efforts being “irrelevant” to the older reservists—that ideology took a less important position in the minds of most of these men while they were doing the unthinkable.3 In so doing, Browning would leave himself open to criticism from another scholar who had a far more vested interest in presenting the actions of the Nazis in a much more villainous light.

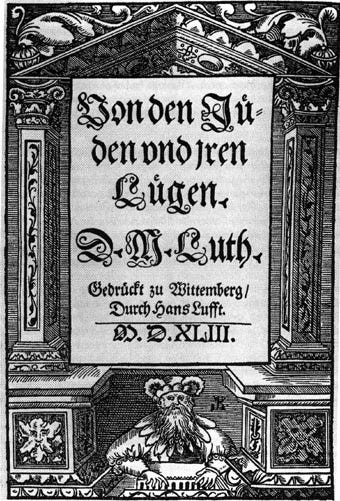

When Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust was published in 1996, its author Daniel Jonah Goldhagen became an almost overnight celebrity, including, most notably, in Germany. Influenced by the old intentionalist school of scholarship that emphasized German Sonderweg thesis, in which “Germany developed along a singular path, setting it apart from other countries,” Goldhagen claims that antisemitism—and antisemitism alone—was the driving force of the Holocaust and its perpetrators.4 By examining not just the role of the police battalions (including the 101), but also the role of particular labor camps and death marches and the cruelty found therein, Goldhagen takes his argument a step further. According to Goldhagen, this “eliminationist antisemitism” was a feature, not a bug, of German culture since the days of Martin Luther. Indeed, he explains it as something that “does not appear, disappear, then reappear in a given society,” and that it is “always […] more or less manifest.”5 This ever-present hatred was merely amplified with the emergence of the Nazis and set loose upon the Jews of Europe, with German gentiles in particular seemingly chomping at the bit to be given permission to act savagely, as Goldhagen would have it.

This claim remains in stark contrast to previous and especially subsequent scholarship, not just from the likes of Browning, but also Ian Kershaw, who has written that the Holocaust began, at least in some places, as an improvisational affair; as Kershaw writes, “improvisation by the German authorities on the spot played a decisive role in the autumn of 1941.”6 According to Kershaw, the genocide was only truly programmatic after ghetto liquidation orders had been given by Himmler and deportation orders had been given by Adolf Hitler. Like Browning, Kershaw had not claimed that there was no ideologically-driven intent (much less antisemitism) fueling such actions. Far from it: he had described the time leading up to these orders as being characterized by “'fantasy' talk of liquidating Jews”; “fantasy talk” still establishes intent.7 However, this was not the kind of conclusion for which Goldhagen was searching; it was merely the conclusion against which he was reacting.

While Goldhagen's own conclusions are almost universally discounted by historians today, his work continues to be frequently cited by them, usually in the context of exploring simplistic Holocaust scholarship, and in treating Hitler's Willing Executioners as a cautionary tale for future historians. This is a fair assessment when examining the work on its own merits (especially compared to its primary target, Ordinary Men), but the work generated enough interest in the Holocaust as a topic that it would be wrong to say it was not significant in the historiography, especially in its weaknesses. In avoiding the hubristic mistakes made by Goldhagen, the modern era of Holocaust scholarship defined itself and within only a few years, a closer examination of the German motives for the Holocaust was made and left further room for more sophisticated development.

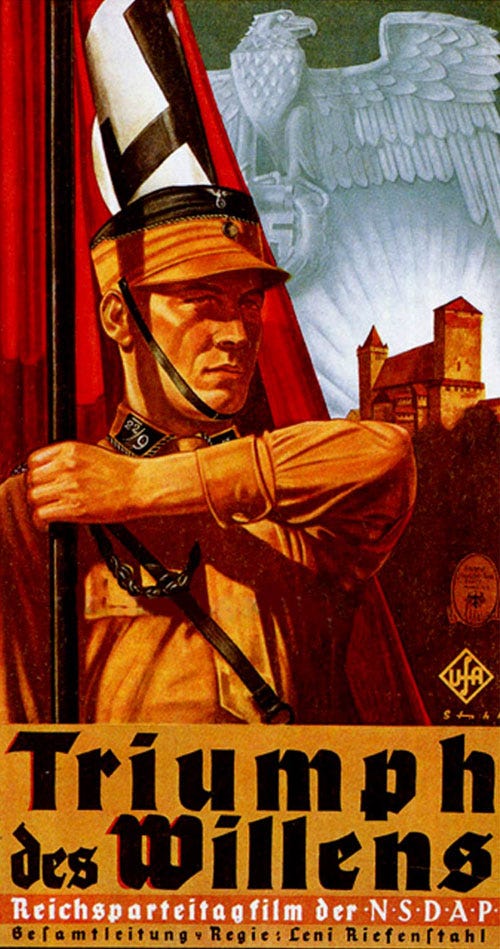

Robert Gellately's Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany (2001) is one of the first pointed examples of post-Goldhagen Holocaust scholarship that widens the lens to examine the Third Reich as a whole as well as leave room for the motives of German individuals to be scrutinized. Like Goldhagen, Gellately examines the tolerance many ordinary Germans had for the Nazis' increasing radicalism over the course of their reign, but he diverges from Goldhagen by emphasizing the different, often complicated motives at work among German citizens. Indeed, Gellately argues that the Nazis themselves always actively sought to be a popular political movement, and this often required them to both convince and sometimes even coerce the support they received from the German people. As Gellately writes, “the Nazis did not act out of delusional or blind fanaticism in the beginning, but with their eyes wide open to the social and political realities around them,” taking a kaleidoscopic approach with policies and propaganda, after which “the public inexorably became entangled in the discriminatory side of the dictatorship, including in the persecution of Jews.”8

Primarily using Third Reich-era newspapers, recorded radio broadcasts, and propaganda films, Gellately demonstrates that, unlike Goldhagen's contention that the antisemitism was simply a monocultural norm animating everything, the Nazis very consciously implicated the public in what they were doing. As Gellately argues, “the rationalizations the Nazis provided the German public about why new forms of coercion and new laws were needed were an integral and essential part of the discrimination and persecution.”9 Far from claiming that the German people were merely brainwashed or thuggishly coerced into accepting the new regime's definition of normal, Gellately continues the work established by Browning that complicates such narratives by looking at their own agency in the face of mounting social and political pressure.

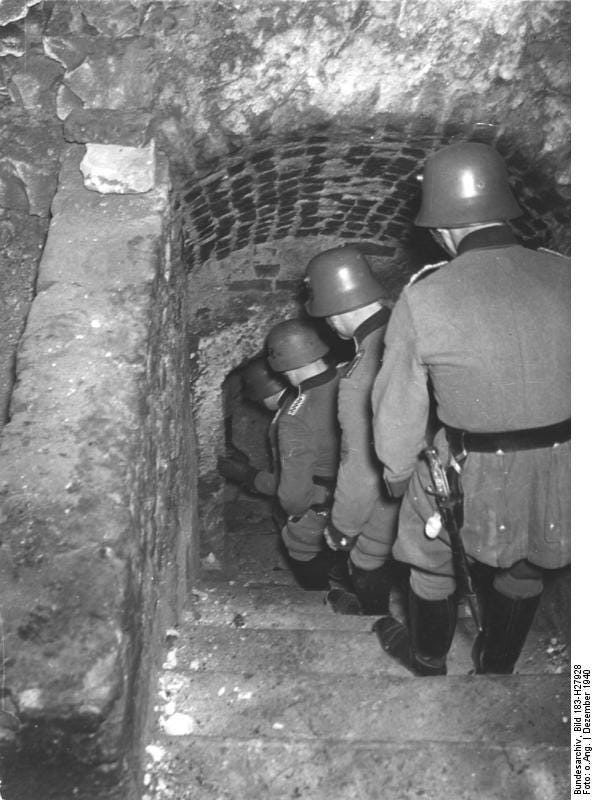

The fact remains that not all Germans approved of what was occurring, ostensibly in the name of their Volk. The Nazis were able to use the German people's own fears of street violence and crime—with which the Nazis had helped facilitate in both the 1920s and 1930s during their battles with the communists—and thus justify their new approach to law and order in the eyes of the people, reflected most obviously in the popularity of the “Day of the German Police” celebration, which according to Gellately, “proved so popular, that by 1937 [it] became a weeklong event.”10 However, despite the public's willingness to largely put its trust in Germany's police forces (including the Kripo and Gestapo, despite the latter's fearsome reputation), they were not always willing to go along with the Nazis' schemes, particularly when it came to the treatment of Jews. This is how Gellately directly challenges Goldhagen's notion that antisemitism was always the animating force behind the Nazis' policies and, more to the point, German citizens' tolerance of them.

For example, during the boycotts of Jewish businesses in April 1933, the public response to the Nazis' insistence on a Jewish boycott was muted; in fact, as Gellately writes, “in bigger cities there were those who made a point of shopping at Jewish stores,” showing that “most citizens certainly did not demonstrate anything like the antisemitic zeal of their leaders.”11 This aversion continued and it was made especially apparent in the aftermath of Kristallnacht. As Gellately shows, while the violence was under-reported in the press and many Germans did not feel free to express their distaste at what had occurred, “in the private diaries of non-Nazis that the riots and the arrests that followed really were disturbing.”12 While Kristallnacht was certainly part of the Nazis' overall plan of doing away with the Jews, it was also part of a larger process. Throughout most of their history, the Nazis were always testing the limits of what they could get away with in the eyes of the German people, and as Gellately shows, it was not always as certain as scholars like Goldhagen would have many readers believe.

Nevertheless, as the war continued, the Nazis could count on the public implicating themselves in the regime's crimes, mostly through the use of denunciations of Jews, Poles, and later, of other Germans. However, while sometimes clearly motivated by truly-felt bigotry, this was not always the case. This latter point is what best challenges Goldhagen's contention of a persistent eliminationist antisemitism animating Germans' support of the Third Reich's more extreme practices to which they were exposed. In fact, most denunciations had little to do with racial “crimes.” As Gellately explains, “the rate of denunciation in the sphere of non-racial 'crimes' was proportionately greater than that obtained when it came to enforcing racial policies aimed at the Jews and the Poles.”13 The reasons for this disproportion falls much more in line with the multivariate explanations provided by Browning in his own work, with the most significant of these reasons being “overt and obvious selfish or instrumental motives”; more to the point, “denunciations were not simply the expression of rabid Nazism, nor […] was overt or obvious racism always the decisive factor.”14

Despite the risk of punishment for frivolous accusations, oftentimes informers simply denounced others as a means to get back at their personal enemies and rivals, and sometimes even hated spouses and family members, which Gellately shows through police reports. This opportunistic reality is also supported by the research of Peter Fritzsche, who writes “local bureaucrats received the applications of townspeople who requested the apartments and furniture of Jewish neighbors in advance of their deportation,” and that as the war went on, “more and more Germans [justified the deportations] after the fact and [felt] vaguely entitled to the spoils.”15 The importance of material gains—and thus, material motives—was given new appreciation in the scholarship.

In sum, Gellately's emphasis on the less-obvious motives of German complicity with the Holocaust shows that Browning's own findings of social influences could be expanded to include many of the very same people who Goldhagen wished to implicate in his own. While Gellately does at times emphasize the importance of ideology, such as the framing of Nazi authorities as Volkisch Polizei, his work serves as more of a de-emphasis on the role of ideology and antisemitism in explaining the Holocaust, and a heightened emphasis on the agency of individuals working and living within the Third Reich. However, this did not close off the reality of role ideology played in the behavior of Germans and Nazis during the Third Reich's reign. As Alon Confino writes, “Ideology is not something produced by the regime and imposed from above, but a product of a process shaped also by individuals, who ultimately changed their most intimate beliefs.”16

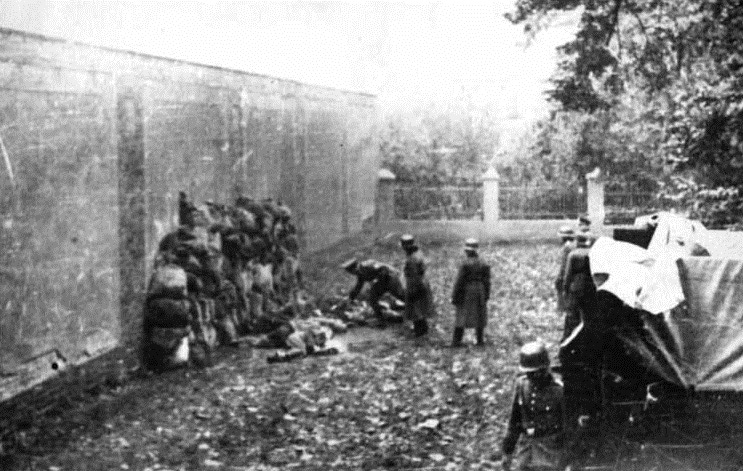

This role played by individuals is articulated at length by Thomas Kühne in his 2010 work, Belonging and Genocide: Hitler's Community, 1918-1945, in which he argues that it was the act of persecution, deportation, and eventually genocide—driven by Nazis' ideological vision—that brought Germans together as a society. This resuscitates the arguments made by Browning about the nature of social conformity but scales it up to the idea of building a community ultimately based on shared complicity of crimes being committed. This does not vindicate the views articulated by Goldhagen, but it does appear to take a page from his approach in examining why there was, for many Germans, a positive connotation in committing such unspeakable crimes. As Kühne writes, “perpetrators and bystanders energized social life and built collective identity through committing genocide.”17

However, Kühne also explains that this identity formed through genocide was complicated, and not merely on the antisemitic bloodlust that Goldhagen attributed to German society as a whole. Using after-action reports and memos as sources, Kühne points out that while many police battalions engaged in cruel and sadistic acts that created a sense of camaraderie among the men who took part, “not all police officers had shared collective joy based on mass murder.”18 However, in discussing this collective joy throughout the monograph, Kühne also acknowledges the presence of the Nazis' antisemitic ideology by asserting that the collective joy existed at the expense of the Other created by Nazi racial ideology. Citing a letter written by a one Lieutenant Werner Gross to his parents, Kuhne writes, “In fighting them, Gross’ men discovered the emotional glue of Nazi virtues: collective joy and dense togetherness, based on the destruction of Them.”19 This is Kühne's greatest contribution to Holocaust scholarship, in which he explains that comradeship—an aspect of the social forces described by Browning—was the basis of carrying out the Nazis' consistently genocidal ideology—an acknowledgment of the ideological importance emphasized by Goldhagen.

Kühne also adds to the claims made by Gellately that the Nazis were constantly testing the limits of what the German people would tolerate, and shows that this was not just part of their strategy on the home front, but with the men fighting on the field as well. The point was to make Nazism a popular movement, supported by the entirety of Germany and carried out by the military. Kühne shows that this can be seen in how the Nazi leadership responded to the protests by members of the officer corps in response to the brutal treatment of Poles during the early days of the war. As Kühne writes, “what [many officers] criticized, though, was exactly what Nazi leaders wanted: a moral revolution through genocidal warfare to create the merciless Volksgemeinschaft.”20 This vision led to Hitler’s issuance of blanket amnesty for any and all crimes committed against the Poles during the invasion, and that rule allowed for further diffusion of personal responsibility by the men themselves and greater cohesion of the men through violence.

While Kühne creates the most compelling synthesis of the ideological and the social interpretations of the Holocaust, he does not emphasize the role of ideology as much as later scholars would. As he writes in his conclusion, “The regime’s racist ideology did not suffice to make enough Germans act according to the new morals.”21 Instead, he argues, it required a far more sophisticated apparatus that prioritized comradeship to the point of making the comradeship the driving force. Kühne does indeed emphasize the importance of the Nazis' racist ideology in creating in the minds of Germans an Other to see as the “Enemy,” but he avoids particularism in order to demonstrate—as Browning did many years earlier—the disturbing universality of what the Nazis did, rather than what they specifically believed. In other words, there was nothing special about the Nazi ideology itself that drove these men to engage in the crime of the Holocaust; it merely served as an effective tool in creating the collective joy and bonding truly required to commit genocide. As Holocaust scholarship continued over the next few years, the particulars of Nazi ideology began to take on a new level of importance and, in turn, shift the focus of asking why the Holocaust happened for its own sake toward asking why it happened in order for modern readers to see it as a warning for the future.

In 2015, the historian Timothy Snyder published Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning, in which he builds upon the arguments he set forth in his famous 2010 work, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin in order to describe the ideological engine that powered such destruction from the Nazis' side. This ideological engine is central to and among the most creative aspects of Snyder's argument, which rests upon the notion that “Hitler strove to define a world without history,” creating a blank canvas determined by the forces of nature.22 In Hitler's world, there was nothing except the struggle of the races, in which the Germans were a strong race made weak by the actions of the Jews and therefore, “they needed to dominate the weaker races they encountered,” and “liberate all races from Jewish domination.”23 According to Snyder, Hitler saw the Jews as the force that created a universal ethic via politics that denied the natural order and thus, they had to be forced into the natural order that they rejected and out of which they supposedly held non-Jews hostage. As Snyder writes, Hitler’s solution “was to expose Jews to the brutal reality that nature and society were one and the same,” ideally through exile to an unlivable locale, with the possibility left open for brutal murder.24 It made no difference.

Snyder argues throughout the book that in order to accomplish this, the Nazis could not merely persecute the Jews while suppressing all political opposition at home. He thus surpasses the arguments made by previous scholars, treating arguments of social conformity, coercion, and comradeship as givens, and even calls to mind the old functionalist arguments of the previous era of Holocaust scholarship. Where Snyder differs from these earlier scholars is his simultaneous endorsement of what would have been called intentionalism, but what today is recognized as an acceptance of ideology's importance. In other words, the ideology of the Nazis drove them to do what they did, but what they did involved starting a war in which they could carry out their ultimate plans, which were firmly rooted in their desire for “living space.” This could only be accomplished through the destruction of states, giving the Nazis true free reign over the shaping of the world into their image.

Snyder's argument about state destruction as a prerequisite for the Nazis' worldview coming into fruition is derived from the arguments he made in Bloodlands, where he makes Stalin and the Soviet Union into active participants that helped create the condition for the Holocaust in Poland. Citing Hitler's orders to his generals on the eve of the invasion, Snyder makes it clear that what Hitler had in mind was not occupation of a foreign country, or even dividing a foreign country between himself and Stalin: it was the complete destruction of Poland as a state. As Snyder writes, “the German invasion of Poland was undertaken on the logic that Poland did not, had not, and could not exist as a sovereign state. […] Once the campaign was over, what began was not an occupation, since by Nazi logic there was no prior polity whose territory could be occupied. Poland was a geographic designation meaning land to be taken.”25 Once that land had been absorbed into the Reich, the people living there became the next barrier for the Nazis to overcome in their pursuit of living space and, more to the point of their ideology, a world made Judenfrei.

Snyder supports his thesis on state destruction serving as the prerequisite for the greatest suffering by internationalizing the crime of the Holocaust. This strain of thinking had certainly been addressed in many works before Snyder's and has continued to take on greater importance with scholarship today, but where Snyder makes this argument unique is in his emphasis on the Nazi ideology that necessitated state destruction. Citing statistics at various points in the work, Snyder shows that the places in Europe that were worst for Jews were ex-states; i.e. states that had been destroyed, rather than occupied. Every state touched by the Third Reich in one way or another lost some of its Jews to mass murder and nearly all of them adopted severe antisemitic policies against their Jews, but survival rates were much higher in places that continued to have statehood. As Snyder explains, “legal discrimination by antisemitic states did not bring an automatic downward spiral toward death, but state destruction did. Once a Jew lost access to a state he or she lost access to the protection of higher authorities and lower bureaucrats.”26

It was not the faceless bureaucracy of the Third Reich that condemned the Jews to their fate; it was the loss of any bureaucracy, which occurred both in destroyed and occupied states. Poland serves as the greatest example of the Jews' vulnerability with its complete destruction by the Nazis and the Soviets, with other states like Romania and Italy serving as examples of places where, even with several examples of brutality, oftentimes many Jews survived the war as long as they were not in places that were fought over and occupied by the Soviets and the Nazis. As Snyder notes in the case of Romania, “Romanian Jews in places where state territory did not change hands usually saw the end of the war.”27 While Snyder spends some time discussing the saviors of Jews—both civilian and military alike—his central argument is that the best protector of Jews during the Holocaust was the state apparatus itself.

Snyder's explanation of Hitler’s antisemitic “zoological anarchism”28 made possible by state destruction is the most unique aspect of his argument, but Black Earth is also positioned among the first of the most recent Holocaust scholarship that treats the Holocaust as a guiding lesson for present and future generations. Contrasting with Kühne, he frames Hitler’s racist ideas not as extreme manifestations of human bigotry (though they certainly were that), “but rather emanations of coherent worldview that contained the potential to change the world.”29 This ability of a worldview to change the world is the universal warning that Snyder wants to apply via the particular ideology of the Third Reich, cautioning the reader that “our forgetfulness convinces us that we are different from the Nazis by shrouding the ways that we are the same.”30

While he uses several examples, Snyder's primary concern seems to be the way Vladimir Putin's Russia has undertaken (as of 2013) similar strategies as Hitler did during the early years of the Second World War, by forming alliances with parts of the European far right. He singles out many other crises and challenges facing the planet—many of which feel prescient with hindsight—including war in the Middle East, American competition with China, and climate change, in order to make his final claim that “understanding the Holocaust is our chance, perhaps our last one, to preserve humanity.”31 While this may be overstating things (and I am inclined to believe it is, given Snyder’s recent turn toward being a political pundit on MSNBC rather than a scholar), Snyder contributed to Holocaust scholarship, especially for more popular audiences moving forward.

By the late 2010s and early into the 2020s, there would appear to be little doubt as to why the Holocaust happened as it did. Peter Hayes' own historical summary written for popular audiences, Why?: Explaining the Holocaust (2017) neatly organizes most explanations given by historians since the 1990s into a comprehensive collection, including explanations for why the Jews were targeted, why the Germans were the ones who did the targeting, why it escalated to murder, and why that murder was so widespread. But following the lead of scholars like Snyder, Hayes dedicated his final chapter to the question of the Holocaust's supposed lessons. Found within that question is the claim, one that has found continued purchase, that “the tragedy of the Holocaust did not end with Germany's surrender in May 1945,” arguing that not only did many Jews suffer and die in the months and even years following the Holocaust, but that it created a legacy in which we continue to live.32 This notion of the story of the Holocaust being essentially unfinished became the central theme of Dan Stone’s 2024 book, The Holocaust: An Unfinished History.

In his book, Stone effectively echoes many of the most pointed arguments made in previous scholarship, including that of Gellately with his examination of how “not all Germans were persuaded by [the] racialization of the social sphere,” as well as how not all Germans were “impressed with the idea of violence against a minority group taking place in broad daylight.”33 Like Gellately, Stone points out how this was known to the Nazi leadership and how they acted accordingly to continue winning over the populace's approval; namely, by keeping the more obvious and abject violence under wraps via controlled news reports and carefully crafted propaganda. However, Stone makes an effort not to downplay the populace's complicity, writing that many Germans objected that “they had to see it and not to the idea that it was wrong to persecute Jews.”34 And like Kühne before him, Stone makes it clear that “violence also produced a sense of community for those on the perpetrator side,” as well as a true sense of camaraderie among both soldiers and citizens alike.35 And finally, like Snyder, Stone also makes it very clear that despite the importance of these “situational factors […] behind them stood a tacit ideological framework, one which did not always need to be articulated because it was widely understood.”36 Taking another page out Snyder's own framework, Stone makes special mention of the Nazis' use of their allies—i.e. states like Romania, Hungary, Croatia, and the Baltic states—to meet their ideological aims, internationalizing the conflict in a similar way, though without the framing of state destruction.

Stone’s perhaps most shocking contention is that nothing can be “taught” by the Holocaust in the way that many have claimed, even refuting the idea that knowledge of the Holocaust can serve its purpose of making sure that the oft-repeated phrase “never again” means anything. Indeed, he writes that “the Holocaust teaches us nothing, since nothing in the end can stop people from supporting these dark forces in times of crisis.”37 As of Stone's writing, plenty of other genocides, many similar in scale as the Holocaust occurred, with nothing being done to stop them, much less by publication of more books about the Holocaust. However, Stone's view is not one of total nihilism; indeed, his observation fits into his own conception of the Holocaust as a warning. As he writes, “the Holocaust is not just a ‘lesson’ about intolerance or hatred but [it] tells us how societies in crisis can slide into horror, with the majority, including established elites, colluding in the worst sort of crimes if they sense that their positions might otherwise be threatened.”38 The fact that this can be considered in more universal terms along with the fact that genocide was not curbed by Holocaust scholarship demonstrates where Stone has somewhat broken with the relatively recent trend toward treating the Holocaust as a warning. He does not suggest or even imply that his work will help stop the next genocide but rather, that the Holocaust indicates many things about the human condition through its ideologically-informed methodology.

Like Snyder, Stone references many modern threats to democratic processes and the general rise of nationalistic excess in many places once thought to be inoculated against such tendencies, but unlike Snyder, he does not imply that any contemporary leader is the modern equivalent of Hitler, in terms of expansionist ambition, policy, or racism. Instead, Stone places more focus on historical memory, both in the last fifty years of the twentieth century, as well as the first two decades of the twenty-first. Instead of the Holocaust's historical memory serving as a “consciousness […] in favor of human rights, cosmopolitanism and progressive ideas,” it has instead become a rhetorical cudgel and a means “to further nationalist agendas, to facilitate geopolitical alliances on the far right, or to ‘expose’ progressive thinkers for their supposed antisemitism or anti-Israel bias.”39 As Stone contends, the problem is not that people do not know of the Holocaust; based on the scale of cultural commemoration and its rhetorical power—which goes well beyond even the examples Stone provides—it is obvious that plenty of people have at least a cursory knowledge of it. The problem is that people do not understand it. Indeed, he leaves the reader with the final question: “The challenge remains: will the Holocaust be understood?”40 In that sense, the history of the Holocaust remains unfinished.

Whether or not the Holocaust should or even can serve as a universal warning for the excesses of totalitarian regimes is certainly up for debate, especially given the presentism it tends to invoke and the possibility of reducing such a cataclysmic event to a morality play that we must not forget. As Confino writes, “The tacit expectation [...] that all people should internalize the Holocaust is an idea invoking redemption, not a historical argument.”41 However, it is clear that the current consensus among most twenty-first century historians of the Holocaust is that it should serve this purpose of warning contemporaries of how far certain countries have gone—and how far they brought their own citizens along—to create a pure vision of themselves and how that could happen again.

It is perhaps unsurprising that the scholarly trajectory went in this direction after the original debate between Browning and Goldhagen rocked the world of Holocaust scholarship. With Browning's work offering a disturbing, universal argument and Goldhagen's offering a more provocative and particular one, it appeared that two camps were established. However, with most historians finding little to recommend in Goldhagen's work thanks to its myriad flaws, the more universalist view of the field understandably and quickly won the day. As more evidence was accumulated that what compelled ordinary Germans to do and accept the unthinkable was something possessed by every man, woman, and child on earth, it was only natural for the Holocaust to become framed as a warning to the darkest excesses of the human condition. If it could happen then and there, it could happen anywhere; that was likely the thinking. Following a decade of research into the social motives of the Holocaust's perpetrators and enablers, a renewed emphasis was placed on the importance of Nazi ideology, but never leaving behind the universalist interpretations of previous scholarship. The evidence for the social motives was simply too robust. Thus, the Holocaust, even in its particular circumstances, had a universal quality and it became the supposed job of the historian to make that clear, if only to justify the dark implications of such a universal interpretation. It leads one to wonder where the field may or even can go while rooted in this scholarly paradigm.

While the current state of Holocaust scholarship may not be ideal, it has very little risk of disappearing or remaining (or becoming) stagnant. The risk of presentism, hyperbole, and moralizing that comes from scholars treating the Holocaust as a warning may have a positive trade-off. The urgency this creates may incentivize further study of this event and thus create a greater understanding of aspects that have yet to be considered. If that is ultimately the case then perhaps this modern framing will have served its best purpose.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Browning, Christopher R. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

Confino, Alon. “A World Without Jews: Interpreting the Holocaust.” German History 27, no. 4 (October 2009), 531–559. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerhis/ghp085.

Fritzsche, Peter. “The Holocaust and the Knowledge of Murder.” The Journal of Modern History 80, no. 3 (September 2008), 594-613. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/589592.

Gellately, Robert. Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany. Oxford, U.K: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. New York: Vintage Books, 1996.

Hayes, Peter. Why?: Explaining the Holocaust. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017.

Kershaw, Ian. “Improvised Genocide? The Emergence of the 'Final Solution' in the 'Warthegau'.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 2 (1992), 51-78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3679099.

Kühne, Thomas. Belonging and Genocide: Hitler's Community, 1918-1945. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

Snyder, Timothy. Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning. New York: Crown Publishing Group, 2015.

Stone, Dan. The Holocaust: An Unfinished History. Boston: Mariner Books, 2024.

FOOTNOTES:

1. Christopher R. Browning, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 175.

2. Ibid., 12.

3. Ibid., 184.

4. Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), 419.

5. Ibid., 43.

6. Ian Kershaw, “Improvised Genocide? The Emergence of the 'Final Solution' in the 'Warthegau',” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 2 (1992), 74.

7. Ibid.

8. Robert Gellately, Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany (Oxford, U.K: Oxford University Press, 2001), 4, 5.

9. Ibid., 7.

10. Ibid., 43.

11. Ibid., 27.

12. Ibid., 128-129.

13. Ibid., 188.

14. Ibid., 193.

15. Peter Fritzsche, “The Holocaust and the Knowledge of Murder,” The Journal of Modern History 80, no. 3 (September 2008), 610-611.

16. Alon Confino, “A World Without Jews: Interpreting the Holocaust,” German History 27, no. 4 (October 2009), 539.

17. Thomas Kühne, Belonging and Genocide: Hitler's Community, 1918-1945 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 1.

18. Ibid., 58.

19. Ibid., 125.

20. Ibid., 103.

21. Ibid., 167.

22. Timothy Snyder, Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning (New York: Crown Publishing Group, 2015), 7.

23. Ibid., 8.

24. Ibid., 10.

25. Ibid., 105.

26. Ibid., 222.

27. Ibid., 234.

28. Ibid., 241.

29. Ibid., 321.

30. Ibid., 324.

31. Ibid., 344.

32. Peter Hayes, Why?: Explaining the Holocaust (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017), 300.

33. Dan Stone, The Holocaust: An Unfinished History (Boston: Mariner Books, 2024), 70.

34. Ibid., 71.

35. Ibid., 73.

36. Ibid., 114.

37. Ibid., 28.

38. Ibid., 28-29.

39. Ibid., 214.

40. Ibid., 225.

41. Confino, “A World Without Jews,” 533.